Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Artist and writer Alissar Seyla reflects on the sacking of Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino from the Australian pavilion in Venice earlier this year. Whilst the artist and curator have since been reinstated, the move by Creative Australia was, Seyla argues, indicative of a wider approach to culture within this, and other settler colonial states, that claim ‘social cohesion’ and institutional ‘neutrality’ as cover for silencing politically dissenting voices and to push through exclusionary cultural policies.

Introductory notes

This article is an attempt to make sense of the ‘Australian’ art system and its failures. Written as a Lebanese researcher, writer and visual artist currently practising in Narrm, or ‘Melbourne’, in ‘Australia’, it is the outcome of much research and reflection. What follows are my thoughts as I navigate a landscape where supporting myself financially through secure, ongoing employment is dependent on whether or not I self-censor and refrain from showing public grief and outrage at the ongoing genocide of Palestinians as well as the brutal attacks on my homeland. Because of the generosity of a few people in Narrm I have been able to maintain a connection to art spaces and have continued my practice through the darkest moments of the past eighteen months.

I am writing here for an international platform whose readers may as yet know little about the controversy regarding the Australian Pavilion at the 2026 Venice Biennale, the initial impetus for L’Internationale Online’s editors to commission this piece. The editors requested a text that addressed the mistreatment of Lebanese-Australian artist Khaled Sabsabi by the national funding agency Creative Australia. These egregious actions raise issues of government interference in arts and cultural institutions, censorship masked as community safety, and a funding body’s self-regulated definition of art and its purpose.

With the 2024 Golden Lion in Venice going to artist Archie Moore, a Kamilaroi and Bigambul man with British and Scottish heritage, there might have been an external assumption that Australia was in some sense addressing its colonial history through art. Sadly, subsequent events have proven the opposite: Sabsabi’s mistreatment demonstrates a growing trend of censorship by Australian arts and cultural institutions to silence political dissent. I have chosen therefore to outline the current situation regarding Sabsabi before expanding on what this one incident might say about this situation in a settler-colonial nation more broadly. Then, rather than pretend that any of us are uncompromised in the complex systems we all move and exist in – rather than to attack or blame – I will try to write honestly about the spaces we occupy.

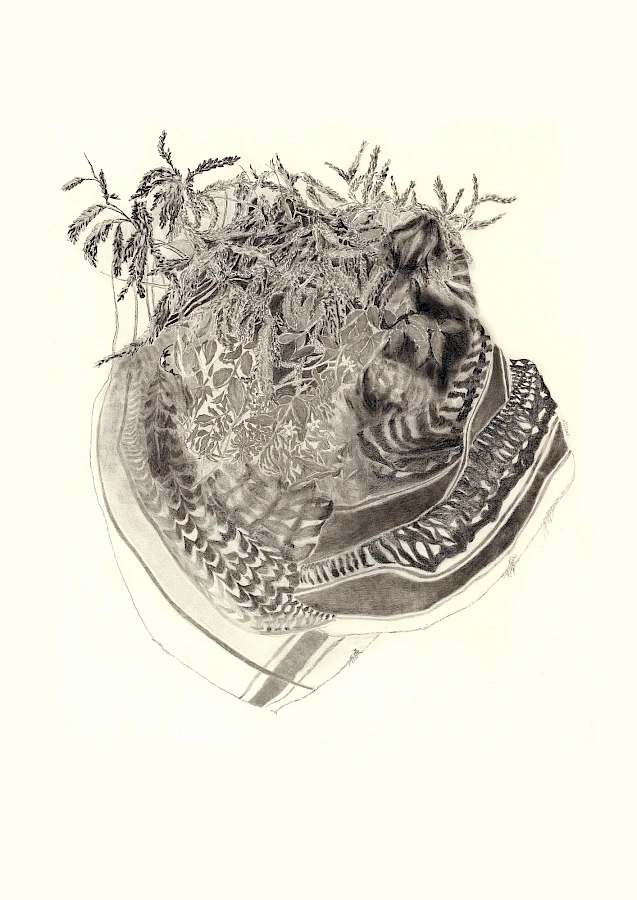

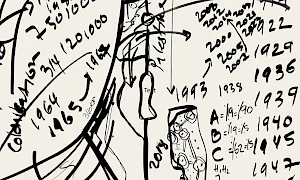

Seyla, A., Of this land, 2023, charcoal & graphite on paper. Image courtesy of the artist.

Khaled Sabsabi and Creative Australia

For readers unfamiliar with Khaled Sabsabi’s mistreatment by Creative Australia, it is worth recounting the key events. Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino were chosen to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale in February 2025. For reasons that can only be described as political theatre, following a media smear campaign shortly after his selection was announced, the shadow arts minister and Liberal politician, Claire Chandler, framed Sabsabi’s previous work as politically contentious in the Australian Senate.1 One of the works referred to in the senate was YOU (2007), a multichannel sound and video installation addressing the brutality of the thirty-four–day war in Lebanon in 2006, which features footage of now deceased Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah.2 The second piece, Thank You Very Much (2006), features footage of the September 11 attacks.3 Though both works are deliberately ambiguous, Sabsabi was openly accused of sympathizing with and promoting terrorism by Senator Chandler and the Murdoch press that dominates media in this country.4 Having received a call from Minister for the Arts Tony Burke, and fearing controversy, Creative Australia’s board unanimously agreed to ask both Sabsabi and Dagostino to resign, just six days after their appointment.5 The duo refused, and their invitation was withdrawn immediately. As far as I know, at the time of writing, they are still waiting for 90 percent of their respective fees as artist and curator to be paid.6

Chief Executive Officer of Creative Australia Adrian Collette explained that the sacking was done to avoid prolonged debate and threats to ‘social cohesion’, against the fear that political controversy might call into question the organization’s social license and endanger its support from stakeholders, from within government and among the general public.[7 At a Senate estimates hearing in February 2025, Collette defended the decision as follows:

Art has always occupied the complex and often uncomfortable space where competing perspectives and social pressures intersect. Maintaining social cohesion is a national priority, and the issues we are confronting are being navigated not just by artists and arts institutions or organisations but by workplaces, universities and communities.8

This statement is a non sequitur. Art’s ‘occupation’ of uncomfortable space cannot, on any terms, have ‘social cohesion’ as its goal. Nor is sacking Sabsabi justified by the fact that the ‘issues’ he addresses are currently being ‘navigated’ outside the cultural sphere. Rather, it seems to me, here ‘social cohesion’ appears as a convenient alibi for censorship.

The origins of the social cohesion argument might be traced back, at least in part, to the key findings of the ‘National Arts Participation Survey’ carried out in 2019 by the Australia Council for the Arts, Creative Australia’s predecessor. This affirmed that art and creativity can be positive indicators of social cohesion and intercultural empathy and that they can help build a shared sense of national identity.9 However, the subsequent sleight of hand that essentially swapped an effect, or consequence, of art on society for its underlying purpose is extremely dangerous. Creative Australia’s functions do not include any explicit mention of responsibility to proactively maintain social cohesion. They do, however, include other kinds of responsibilities: to promote the safety of artists and their artistic expression, to safeguard a diversity of creative practices and to provide community advice and evidence-based recommendations to the federal government.10 These functions, enshrined in founding legislation and operationalized in policy, are supposed to be conducted free from ministerial influence. This was clearly not the case for Sabsabi’s sacking. Collette admitted in a parliamentary session that, after Chandler called attention to it in the Senate, he had received a phone call from arts minister Burke expressing ‘shock’ over Sabsabi’s work and questioning Creative Australia’s next steps. Remarkably, Collette claimed that he had already taken all the actions Burke asked of him, in the minutes before the minister called.11

In the hearing, Senator Chandler asked why a thorough vetting of Sabsabi’s previous works had not taken place and raised a ‘conflict of interest’ issue regarding the artist’s boycott of the 2022 Sydney Festival, after it obtained funding from the Israeli Embassy – even though an artist’s political views are not deemed relevant to the Venice Biennale selection process.12 The chair of the Creative Australia board, Robert Morgan, said there was no ministerial influence on the decision to cancel Sabsabi and Dagostino’s contracts, but statements from both him and Collette made throughout the Senate hearing suggest that ministerial pressure factored into decision-making, breaking their own ‘arms-length from government’ rule, while the board’s decision undercut that of the expert committee that had selected the pair.13

It is important to add that the committee’s selection processes are not above criticism. They seem to have changed recently to give Creative Australia and its CEO more power, and many have called for them to be reviewed.14 My contention here is that the attempt to sidestep further ministerial scrutiny and ongoing media controversy by firing Sabsabi and Dagostino goes against Creative Australia’s own founding mandate, aligning the organization not only with Australian government policy (which is in full support of the Palestinian genocide) but also with the questionable view that art should be confined to work that only has ‘socially cohesive’ effects. With a casual wave of the CEO’s hand, it is implied that art should not stimulate thought or discussion dissonant to the political status quo.

Given the level of incompetence they demonstrated, it is entirely possible that Collette and Morgan are not aware of the implications of their decisions, but that does not mean others should not take their words seriously. The right to disagree in a democracy extends to artistic expression, and Creative Australia is charged with protecting the right of all artists to convey a plurality of viewpoints (political or otherwise).15 For failing to do so, Collette has been called on to resign publicly. To date, he has been served with two letters of complaint from Creative Australia staff and a third letter, signed by over six hundred Australian literary figures, citing ‘deficiencies in leadership’ and fears of discrimination on the basis of religious, cultural and political views.16 As Professor Anthony Gardner rightly observed, ‘the moment [Collette and the board] were caught between supporting the artists and keeping an organization’s status quo and choosing not to support the artist – that is the moment their positions became untenable.’17 At the time of this text’s publication, Morgan has ‘retired’ honourably and is leaving the board soon, while Collette remains in post.

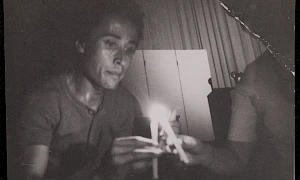

Artist Khaled Sabsabi and curator Michael Dagostino, 2025. Photo: Bec Lorrimer/The Guardian

Censorship, diversity and racism policy

Even with the latter’s resignation and disgrace, and the reinstatement of Sabsabi and Dagostino, the fundamental need for reflection and action would remain urgent. Creative Australia’s blatantly racist attack on Sabsabi is not an isolated incident. Calling it out without examining the wider context in which it occurred clouds the deeper issue of structural racism in Australian arts and cultural institutions at large. Speaking at a recent event in Narrm, Louise Adler described the long history of political meddling and racism in the arts, including the way that the Zionist lobby in Australia has successfully ‘turned the focus from ethnic cleansing in Palestine to a wildly exaggerated campaign against antisemitism’.18 Due to this shift, the view of Sabsabi’s work as compelling and socially engaged flipped very quickly to that of its being ‘divisive’ and ‘antisemitic’.19 The Creative Australia debacle came about at a time when institutions fear to appear to be affiliated with individuals, particularly Arab Australians, who engage with politics either through their work or in their private lives.20 Thus, by Collette’s own admission, due to the obstacles, stated above, that Sabsabi has to face as an Arab-Australian artist, the fear was that Creative Australia would suffer reputational damage as a result of honouring his contract.21

The sacking of Sabsabi was preceded by pressure from government and interest groups that resulted in cultural censorship and was followed by further silencing and erasure: the initial, though later rescinded, postponement of Sabsabi’s show at the Monash University Museum of Art a few weeks after he was sacked is a case in point.22 Other actions, such as the State Library of Queensland stripping First Nations author, K.A. Ren Wyld, of a 15,000 dollar black&write! fellowship for sharing Gaza-related content on social media (May 2025),23 censorship of the Palestinian flag at the National Gallery of Australia (February 2025),[twentyfour]] and the firing of four pro-Palestinian writers from the State Library of Victoria (March 2024) under the guise of cultural and child safety policy,25 reveal the efforts to eradicate voices that refuse to remain silent in the face of Palestinian genocide.

Around the same time that Sabsabi and Dagostino were fired, Universities Australia adopted a definition of antisemitism (for application within the organization and with regard to their member universities’ racism policies) based on that of the contentious International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), which conflates both criticism of Israel and support for Palestinians with antisemitism.26 The definition, which was adopted without adequate consultation with the National Tertiary Education Union, university students or staff, posits that while criticism of the Israeli government may not be necessarily antisemitic in itself, ‘criticism of Israel can be antisemitic when it is grounded in harmful tropes, stereotypes or assumptions and when it calls for the elimination of the State of Israel or all Jews or when it holds Jewish individuals or communities responsible for Israel’s actions’.27 The adoption of this deliberately ambiguous definition is politically motivated, intended to silence students, academics and other university staff engaged in pro-Palestinian debate and activism.28 It is particularly shameful to censor community grief when Palestinian and Arab lives and deaths are being treated with no small amount of disrespect by politicians and the mainstream media.

Professor Ghassan Hage, himself fired for speaking up against Israeli violence in Gaza,29 is one of the only Australian intellectuals to have clearly articulated that it is the ‘logic of war’ to silence Palestinians and those who are pro-Palestinian, and that this is being done in the name of so-called ‘diversity policy’.30 In a media release opposing the IHRA definition, The Jewish Council of Australia has condemned its adoption as ‘dangerous’, stating, ‘it threatens academic freedom, will have a chilling effect on the legitimate criticism of Israel, and risks institutionalizing anti-Palestinian racism’.31 In spite of this, it has now become the only form of racism and discrimination policy that is included in the Higher Education Standards Framework, which is charged with protecting the safety and wellbeing of under-represented and disadvantaged groups in institutional policies and practices.32

Political neutrality and community safety

The root of these exclusionary guidelines is not in fact ‘social cohesion’ but rather the older, liberal doctrine of institutional ‘neutrality’ towards art and culture. History tells us that adopting a position of neutrality is itself a political position. The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which emerged in the 1950s and 1960s in the face of an ideologically bipolar world, formed a united front of postcolonial states working towards decolonization, anti-racism and noninvolvement in global power conflicts, being thus opposed to apartheid, imperial expansionism and Zionism.33 Based on principles of transnational solidarity and the integrity of state and territorial sovereignty, member nations sought to focus on their own national development concerns while taking a position of neutrality towards and noninterference in the matters of other states.34 However complicated this was at the time, the NAM alliance was clearly framed to strengthen solidarity in and between developing nations while challenging the new forms of colonialism being developed in ‘the west’. In a world order based on western hegemony, NAM maintained a position of both neutrality and anti-racism.

After the collapse of the bipolar world order around 1990, the notion of neutrality came to be linked to ideas of artistic (not political) autonomy, as museums and art institutions began to proclaim their own neutrality as a way of giving voice to artists.35 Disconnected from demands for broad social and economic justice, this new neutrality was not de- but re-politicized in favour of the status quo and the interconnected systems rigged to the advantage of countries in the Global North.36 The claim to neutrality as an apolitical position in the art field today should therefore be understood as a misnomer that is bound to (and powered by) ideologies of colonialism and exploitation of the Global South.

In the context of Australian arts and cultural institution policies, ‘neutrality’ is used to enforce a veneer of impartiality, supposedly not favouring one cultural, ethnic or ‘othered’ group or political standpoint over another. Rather than a clearly articulated and formalized strategy, the result is that institutions assert bias through western definitions of multiculturalism and universality, allowing for censorship to occur under the guise of safety frameworks and diversity policies. Writing about museums in the United States, Laura Raicovich argues, ‘neutrality and universality is claimed on behalf of a white, Euro-American perspective. Under the banner of universality, neutrality hides that there has always been a perspective, a set of biases, an exclusivity, that is at its core political and has always been.’37 ‘Neutrality’, as a policy to cover institutional bias, is a highly politicized directive manufactured to serve certain individuals, systems and ideologies.

‘Neutrality’ is adopted as a necessary condition for ‘cultural safety’, another concept that is used by institutions and policymakers to show an (often superficial) understanding of intersectionality and commitment to creating environments conducive to inclusion, healing and empathy. Originally based on the practice wisdom of healthcare providers engaging with people from Māori communities in Aotearoa, or colonial New Zealand,38 cultural safety guidance has been adapted to people from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander backgrounds in Australia,39 and more recently, applied to those from immigrant and refugee communities.40 It is a valuable tool for Australian health and social services, supporting quality of care and reflexivity among those working with communities labelled as ‘other’ and marginalized by government systems. Its application in arts and cultural institutions, however, seems to be more in service of silencing ‘othered’ voices that are not perceived to be neutral or socially (read: politically) cohesive.

The term has been effectively weaponized to exclude artists deemed dangerous due to their Arab- or Muslim-ness and/or pro-Palestinian views. The State Library of Victoria, for example, demonstrated its abuse of ‘cultural safety’ policy in the name of neutrality by firing pro-Palestinian writers in early 2024 and issuing a ban on the expression of political views by any staff member, with public-facing staff specifically advised not to wear anything that could be deemed supportive of Palestine.41 Internal documents released under the state Freedom of Information Act reveal that executive staff and board members discussed the religious and political views of these writers prior to cancelling their contracts, going so far as to consult with the government before making a final decision.42 One board member, a former Member of Parliament, warned that the Library was required to ‘adhere to a policy of strict neutrality’, which meant that, ‘on a subject such as Gaza/Israel we have a duty to be absolutely thorough and super careful about the way language is used by the people we engage’.43 In other documents, staff targeted Omar Sakr, an Arab-Turkish Muslim poet, stating that his subject position required further ‘risk management’ and raised concerns about cultural and child safety.44

Censorship of Palestinians, Arabs and Muslims took place in Australia well before 7 October 2023. However, due to the subsequent escalation and scale of violence against Palestinians (and, to a much lesser degree in Australia, Arabs in general and those who are supportive of Palestine), there is now rightly a debate in Australia, as elsewhere, about whether arguing for a ‘neutral’ position is tenable, particularly in times of conflict, and whether it serves the needs of multifaith and multiethnic communities. Political bias informs arts and culture institutional policies in Australia. It is driven by western-centred, settler-colonial ideology and its supposed neutrality, and the resulting forms of censorship and cancellation are erasing voices.45 This needs to be acknowledged and actively addressed with fearlessness. The current problem has two interlocking components: (1) institutions are facing huge pressure to sustain operations in global minority countries (particularly the settler colonies of Australia and the United States) at a time of economic precarity and increasing state hostility towards arts and diversity; and (2) empowered by structural racism, the managers of arts and cultural institutions are choosing to be complicit with the state-level silencing of those voicing support for Palestine rather than serving artists, art workers and communities. Australian pundits point to Trump’s defunding of the arts as a dangerous trend making its way to our shores, and frame any type of political dissent as potentially harmful, leading to government scrutiny, slanderous media campaigns, and loss of funding.46 This argument accounts in large part for the silencing of criticisms of Creative Australia, particularly since it announced an independent review of governance processes to inform ongoing and future decision-making with regard to the Venice Biennale.47

The second part of the problem refers to the foundational ideologies of arts and cultural institutions. There is a longstanding story many workers tell themselves about being able to change systems from the inside, fuelled by beliefs that diversity and inclusion are hard-won in the elitist realms of Australian creative industries and that any kind of diversity is better than none at all.48 This narrative follows an incrementalist logic: that policy moves slowly along a linear path, that big change is too disruptive and divisive, that expecting too much too soon is unrealistic.49 It makes sense within the boundaries of a risk-averse, conservative worldview, one that hides behind realist or ‘pragmatic’ thinking and sees accelerated change as damaging to ‘social cohesion’ or, as Adler described it, ‘banality by misdirection’.50 But policy-making is not, as we know, a straightforward, linear process: it is dependent on the whims of dominant powers and subject to a multitude of global and local pressures.51

Recent expressions of support for Sabsabi from artist-run associations, galleries, individual artists and artworkers, many of which are funded by Creative Australia but not directly representative either of Australia or of a particular state or territory, are in large part due to embarrassment over how Creative Australia’s actions play out on an international stage. While it seems tangible to grasp (on a surface level at least) that it is wrong for an individual artist to experience a blatantly racist attack, the prospect of addressing the overwhelming scale of structural racism that permits censorship of political critique in Australia while ignoring genocide in Palestine appears to be a critique too far. Here it is crucial to understand that the root cause of attacks on Sabsabi is the genocide in Palestine itself. The genocide, or rather Australia’s tacit support of Israel’s genocidal war, is what has framed Creative Australia’s reading of Sabsabi’s Arab-Australian identity as well as a number of his artworks that respond to situations in his birth country of Lebanon. Yet, for the funding bodies that keep arts and cultural institutions alive in this country, it has proved much easier to display solidarity with one Arab-Australian and express support for that individual’s right to artistic freedom than it has been to take a fundamental, moral, anti-racist stand against horrific, ongoing violence backed by government support.52 Maintaining a focus on one individual as an isolated incident resulting from external political meddling, as I have discussed, diverts attention towards a strategic error made by one government organization and away from the root institutional problems.

Photograph taken from the Australia Palestine Advocacy Network (APAN) webpage promoting the event Symposium: Blackfulla Palestinian Solidarity November 7th, 2023.

Final thoughts

While Creative Australia, the nation’s principal arts investment and advisory body, is tasked with safeguarding artistic expression of diverse cultural identities, it fails to translate this into action.53 The arts and cultural sector is heavily influenced, if not shaped, by Creative Australia in terms of how it reacts to perceived political pressure by enacting policies that enable the implicit censorship of art that does not conform to the political status quo.54 Sabsabi and Dagostino’s unceremonious dismissal was well-documented by Australian news media, in think pieces and in open letters from artists and institutions.55 Sabsabi himself broke his silence about the experience, vowing to make the proposed work and exhibit at the Venice Biennale regardless.56 He has been duly supported by a popular crowdfund campaign, as well as the National Association for the Visual Arts and the artists and curators shortlisted for the Australian Pavilion at the 2026 Venice Biennale.57 However, very few statements of support for Sabsabi make mention of the Israeli assault on Gaza as the cause of such censorship, instead passively gesturing to a turbulent global context and sociopolitical pressures brought about by ongoing conflict in ‘the Middle East’.58

Critical debate about Sabsabi and Creative Australia has shone a spotlight on the inherently political position of so-called institutional neutrality in its attempt to mask structural racism. Such ‘neutrality’ supports a government mired in the ‘logic of war’, and institutions, in their disregarding of the sovereignty and self-determination of Palestine, grant their tacit approval for colonial erasure via genocide, as well as colonial theft of both resources and land.

A joint statement released by Sabsabi and Dagostino (2025) declares that ‘art should not be censored as artists reflect the times they live in’.59 In fact, institutions are self-censoring to avoid discomfort and debate, allowing themselves to be coerced by government ministers and interest groups to secure funding: censorship is expected in return. In this sense, the field of art is reflecting the times, and with very little prompting. The art world adopts an ‘apolitical’ stance that is, in fact, highly political, while opting against political forms of action, critique or empathy. These flawed and diversionary diversity policies shore up and exacerbate the supposed neutrality of arts and cultural institutions founded on colonial violence.

Related activities

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles

Related contributions and publications

-

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials