How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

The forest is alive. It can only die if the white people persist in destroying it

… . We will die one after the other, the white people as well as us. All the

shamans will finally perish. Then, if none of them survive to hold it up, the

sky will fall.— Davi Kopenawa, 20131

They were the fact, not the pretense of being an idea.

They were communal societies, never societies of the many for the

few. They were societies that were not only ante-capitalist, as has been

said, but also anti-capitalist. They were democratic societies, always.

They were cooperative societies, fraternal societies … . They were the

fact, they did not pretend to be the idea.— Aimé Césaire, 19502

Believing in happy endings is our greatest pathology.— Suely Rolnik, 20223

I.

That climate collapse is a colonial achievement, we have known for a long time. That we have universalized the problem so as not to have to assume certain inherent responsibilities and that over the centuries we have created comfortable truths, convenient lies, and dishonest equations to justify our apparatus of violence and privilege, there is no shadow of a doubt. That the fear of the end is, in fact, the fear of a certain end of a certain project (and) of a certain reason – besides its being established: it seems that the applicability of this sentence is ever more evident. That the world has already ended many times, and that insisting on the contrary only proves the hegemony of the discourse, too. That the mountain is not inevitably a condition for the train, another obvious fact; even though the centuries of devastation and ‘progress’ tell just the opposite. That the problem is always the one we don’t want to see, but that we perfectly know how to illustrate nothing could be more symptomatic. That to call ‘a crisis’ what is, in reality, a result of a certain civilization project is nothing new.

That climate emergency, capitalism, and racism are three sides of the same coin, even though it only shows two of them no one will contradict the obvious. That the earth is black, also red, sometimes ochre or yellow, and that the predominant voice in the ecological debate is historically ______ is not only problematic but suggestive. That civilizing shouldn’t be a destiny, and being human is perhaps the greatest hoax of all, we finally seem to be realizing; and it is already too late. That posts and likes accelerate the melting of glaciers; that WhatsApp groups burn down entire forests, and that TikTok videos kill whales; that whoever is not lost does not yet understand. That both capital and modernity and its -isms were our ideas, we who have been too human for so long, indiscriminately conceived in the name of an idea of future that only benefited ourselves, but not all of us – no doubt this is the most basic arithmetic. That humanity is a dangerous invention we have known for a long time, too.

That what we call ‘climate change’ is called ‘white sickness’ by native people – also abuse, extractivism, violence, looting, rape. That what seems to be construction is already ruin. That empathy is a convenient discursive invention, just like resilience and salvation. That nothing is more Western-centric than the apocalypse, and nothing more self-confident than guilt. That, in order to read the circumstances, one must stop being narcissistic. ‘Narcissus finds ugly everything that is not a mirror’, the song goes.4

That reproducing one’s own species in order to save it from the end of the world is just one more capital-logic of art’s survival. That art is, by condition of its existence, colonial, and that appropriation is not an invention of the twentieth century. That its world continues to be colonial and its system too, resulting from universalizing, colonizing epistemologies that we invented based on certain interests; we who haven’t stopped being who we are for a minute, not since five centuries ago. That art can be a tractor – and let cast the first stone, the one who has never run over someone for its sake! That it creates proto-phenomena, feeds statistics, increases fortunes, invents illusory redistributions, and pulls the trigger – all quiet on the Western front. That it saves nothing, and no one; that its world has very little eco-vision; and that it insists on calling ‘ecological’ what, historically, is political – we seem to have arrived at (or returned to) our starting point.

II.

Because every conquest leaves its debts. Because when it seems like construction, it is, in fact, already ruin. Because ‘world fiction’ is an enormous paper tiger that wakes us up every morning with seductive agreements and impossible promises. Because poetry is not rhetoric. Because, as Audre Lorde says, the difference between poetry and rhetoric is being ready to kill yourself instead of your children.5 Because when a chimpanzee is worth more than a rat, we all lose, humans and nonhumans. Because competition is a capitalist invention. Because capitalism does not exist without oppression. Because racism is a dynamo of capitalism.6 Because the world has ended many times, and has been ending for a long time. Because the end of the road is so far ahead that it is already behind us. Because worse days will always come. Because another world will only be possible when we no longer know what we know; but it will still be made of everything we have made, and of everything that must end. Because a world where everything is a beginning has much future, little present, and no past. Because progress is scarcity’s invention; ‘enough’ is a truth that has never materialized, and underdevelopment is a strategy of domination. Because land is a language, and colonialism is a monocultural system.

Because justice and prosperity should be preconditions, but can cost billions. Because expecting the art world to decolonize is stupid, not naive. Because every concept carries with it a history that is almost never fair. Because fairness also has its chiefs. Because light does not tell us about seeing, but precisely about what we do not want to see. Because what we don’t know also exists. Because the dismantling of the art world, as Denilson Baniwa says, is a didactic and cosmological action of likoada.7 Because when Ailton Krenak says: ‘The Earth is our Mother … this is not poetry, this is our life’, he is trying to tell us that life is not useful.8 Because even the name ‘Araweté’ is an invention of kamarã.9 Because in the capitalist world-system, to die mostly means to be killed. Because criticism is also a place of power. Because museums have never been anything else. Because more than places of historical memory, they are historically protagonists in the implementation of the colonial monocultural system. Because in the world of metaphors, everything that is real is also fake. Because it is not enough to change the object if the episteme does not change. Because calling a package of historical violence ‘climate collapse’ is just another erasure strategy. Because what ‘a few select people call the Anthropocene, the great majority is calling social chaos, general misgovernment, loss of quality in daily life, in relationships, and we are being thrown into this abyss’.10 Because it has been in effect for at least 530 years. But you can always go shopping at Humana.11 Because who can really afford organic food? Because to impose an ‘existential turn’ is to enact a massacre. Because the meat is poor, but it means power.12 Because the price to pay is too high, too normative, too cool. Because we still produce what we produce, and for whom we produce it. Because even in the post-binary, post-pandemic, and ‘posthuman’ world there are still those who serve and those who are served. Because art as a way of thinking is no longer enough. Because ‘the Yanomami will not be saved just because Brazil’s biggest museum is holding an exhibit on Yanomami mining’.13

Because ‘naivety’ is a word that we use for everything that we don’t know or understand. Because wanting someone to take a stand is just another strategy to capitalize on their discourse or on cancelling it. Because we are all tired, but some will always be more tired than others. Because the sun does not shine for everyone. Because the intellectual left is no longer sustainable. Because the trigger continues to be pulled by the same fingers. Because if it was once a colony, it is now an evangelical corporate parastate. Because if it was once 1492, it still is. Because, as Achille Mbembe said, contemporary racism resides in the interconnection between the radioactive and the viral, that is, it is the sum of a direct, visible and immediate violence with a slow and gradual one, which little by little makes unfeasible and prevents basic rights.14 Because we have never been so medieval, nor so terribly modern. Because we steal land. Because we kill each other. Because we are incapable of considering a river that is sick as our grandfather.15 Because there are more things between heaven and earth than are dreamt of in Western philosophy. Because our guilt continues to be Christian and science does not relieve us of it. Neither does art. Because it is wallowing, and we are wallowing in it. Because, as Fanon announced, ‘the explosion will not happen today. It is too soon … or too late’.16 Because it may be the end of everything, but it may also be the end of nothing.

III.

What can the art world actually do with a snake-letter? What place does it have for a jararaca dream?17 What ethical structure is art capable of building, in order to deal with what it does not invent? How does it behave when it cannot retain codes that do not belong to it? How does it fail to illustrate what it does not know? How does it exhibit, and exist, without aestheticizing everything? Is it from within that we break with the pedagogies of power? What social, political, and environmental responsibility are we effectively assuming in our practices? How to go beyond the ‘magic words’? What are we really capable of building when everything is burning around us? To what extent does our critical discourse and our activist posture prevent lives from being made precarious? How can we, in our practices, avoid making aesthetics of disgrace, praising guilt, falling into politics of salvation? How to go beyond simulations of experiences, falsifications of situations, the logic of models, programmatic captures, and the paralyzing institutional gases? How do we do all this when the political situation summons us to defend what we believed to be our object of criticism? How to escape the pedagogies of power and be, at the same time, didactic enough? How to be tactically in and strategically out? How not to negotiate the non-negotiable? What, after all, do we consider to be that? Do we really want to question our own statements? Do we really want to unlearn what we know? What effective, non-narcissistic ideas and actions are we building to postpone the end of the world? What effective, non-narcissistic ideas and actions are we building to accelerate the end of the world we have created so that others are possible? Is it possible for us to start over without aestheticizing its end? How can we continue being human, but without knowing what we already know? Are we really capable of imagining a world in which we no longer are (as we are)? What part of what we (re)produce represents structural change, and what remains part of a strategy of consumption? Is art really interested in abandoning the historical project of things?18

IV.

In the institutional art market, one of the most traded terms (and themes) in recent years has been ‘the future’, and especially its possible end – sometimes sold too cheaply, sometimes costly enough, depending on the level of speculation and capitalization on the day. As many who work in this field claim, climate collapse means the end of the future and this is what we need to fight against so the world doesn’t end. This seems symptomatic of a way of thinking that, in reality, has changed little or not at all: we keep looking ahead in order not to have to look back; at the same time, we continue to insist on the idea that History is what is in the past and not the present that we build daily. In both cases the idea of the future is an escape.

V.

In the last decades, there have been many prescriptions for, and attempts at, facing and postponing the end of the world. The same can be said of theories about the loss of the future – on the lack not only of its occurrence, but also and mainly of its representation. Meanwhile, never have so many different futures been projected at the same time – nostalgic, dilated-developmentalist, techno-utopian, disruptive. It is as if the future that no longer exists has become its own simulacrum, while we, under the effect of this future with no future, are lost among transitory worlds that we think we know, but in which we have never been.

Some will call it ‘apocalypse’. Others, ‘posthumanity’, ‘Anthropocene’, or even ‘dystopia’. In all cases the hypotheses, whose link to a specific linear temporality is defined by epistemologies built according to a hegemonic notion of knowledge deriving from the Christian tradition, bond over identifying the future as a project of either damnation or salvation. This means that the terms and concepts created in an attempt to name it are at once infinite and insufficient, because the end of the future represents above all the exhaustion of a certain project of reason and its regulatory and civilizing frameworks. For many native peoples, what we call the future has been under dispute for more than 500 years. For others, the future was never even a possibility; and there are those for whom the future never existed, cosmologically and/or temporally. The planetary collapse we are experiencing does not, therefore, establish or constitute the fact of a common or universal relationship to the future. At least, not to the pimped-out future maintained so far, based as it is in a capitalistic, racializing colonial regime, as Suely Rolnik argues.19

How, then, to go beyond apocalyptic dogma and its politics of salvation, and, at the same time, beyond the very logic that defines it as such? What of the past are we annihilating in its favour? What of the present are we denying while we continue in real time to project ourselves into an apparently lost future built of idealizing utopias (progressive or reactionary)? What exactly do we need the future for, when its relationship with progress is precisely what brought us here? Wouldn’t thinking about the future as something behind us, and the past as something ahead, as the Aymara people suggest, be a way to learn everything we need to unlearn, in order to stop knowing what we already know?

The Bolivian sociologist Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui argues that what the crisis does is to question the words, the assumptions of common being. That is, ‘it questions the fact that we think we understand each other because we take for granted what words like market, citizenship, development, decolonization, among others, mean’.20 These are ‘magic words’, she tells us, ‘because they have the magic to silence our concerns and ignore our questions. What the crisis does, in breaking those securities, is to take us off the ground and force us to think about what we mean by them’.21 And to these, we could certainly add ‘future’, ‘progress’, ‘civilization’. Understanding what we mean by them involves much more than using them correctly. In the capitalist economy of narratives, the boundaries between words of change, watchwords, and trendy words are very thin. The same word can very quickly assume all three undertones, contradicting itself and emptying itself of its possible meanings, potency, or coherence.

VI.

Modernist anthropophagy is just a step away from zombie anthropophagy. In the blink of an eye, we move from anthropophagic micropolitics to the uncritical incorporation of the capitalist politics of the production of subjectivities. When we come to our senses, if it happens at all, we find ourselves devouring self and others in the name of a supposed common good; both inside and outside art, and with less or more decolonial impetus. ‘Narcissus finds ugly everything that is not a mirror’, as the old song goes.22

VII.

In this factual ‘vanity’, the institution of ‘art’ does not stop: it goes on reinforcing its ‘visionary’ role by producing images, generating narratives and ‘trends’, revising discourses, formulating new agendas, exhausting concepts, doing business, moving the chain of production in its own way, and serving delicious dinners for whoever is hype at the moment. The ‘antennae of the race’ (a hideous expression coined by Ezra Pound to refer to artists) don’t stop, either. They keep producing and producing and producing, until, stuck between saving the world in order to fit into the current art discourse and getting sick, they end up exhausted.

The art world dances a strange and convenient dance of contradictions: for the sake of the oceans, the forests, humans and nonhumans, the regeneration of the planet; and also, if not mainly, for that of its own status quo. In the name of the planet’s health and its own ‘decolonization’, it races unbridled toward revisions and new agendas. The changes so-realized are mostly discursive; still barely epistemological, and therefore rarely structural. Thus, it ends up reproducing the capitalist, racializing, colonial regime it claims to oppose, since, as Rolnik argues, the unconscious is not necessarily altered by discourse. (In the name of the planet’s ‘health’, the art world turns its back to worlds, lives, and forms of knowledge it finds uninteresting, even while participating in the devastation of what is left.) This too is, no doubt, a complex mathematics: as long as structural changes are treated only as if they are images (of something), whose purpose is to occupy white cube galleries or specialized publications of restricted circulation; as long as visibility is confused with appearance, and historical debt with agenda, we will hardly move on. If human relationships and ways of being do not change, the contracts remain the same and so do the emergencies.

VIII.

Great fortunes rule governments. Governments are killing people. What do museums do? Northern countries have the ‘best models of education’. Northern countries mine Southern lands. What do museums say? The forest burns. Hunger is back to being a reality. The extermination of native peoples only increases. São Paulo has more than 60,000 people living on the streets. What are museums for? Artists make art. Computers make money. And the museums? How uncomfortable a role are museums really willing to occupy in the so-called decolonization process, beyond just talking about it? What do museums do in the face of massacres and land invasions? What should their role be in these hostile times in which we are living? Illustrating the looting and violence is not enough. What is the measure of comparison between the poetics of doom and the politics of salvation, and what does this have to do with taking ethical responsibility? What does thinking about museum education today consist of? What notion of education is the museum building? What institutional pedagogies structure its practices? Which of them is the museum willing to unlearn?

IX.

Historically, both in the context of art institutions and museums, as well as in the political and social structure in which we live, education has occupied a somewhat paradoxical position: on the one hand, it is recognized as a fundamental place for the exercise of critical and political imagination; on the other, we effectively treat it as a subordinate sector in the hierarchy of institutional discourses and practices.

The enormous interest in education, in the first half of the 2000s, within the cloud of the ‘educational turn’, certainly brought some changes regarding its relevance in the context of art and giving the role of education and pedagogy more attention and a certain respect. This new ‘status’, important for the review of statements and modes of operation, did not, however, guarantee effective structural changes in terms of institutional pedagogies.

By ‘institutional pedagogies’ I mean the set of practices and methodologies that make up and shape an art institution, museum or organization. That is, not only their educational activities and programs, but also and especially their decisions, modes of organization, and structures of mediation from contracts, income, and organizational hierarchies to direct or implicit curatorial, advertising, and educational discourses and choices and the times and spaces in which they take place as well as the question who occupies the chairs and positions.

In view of this, we could say that the sense of education constructed by a museum is indisputably present in the educational activities that are developed for this purpose, but not only in them. It is also actualized in attitudes and practices not necessarily called educational, but which structure the institution.

Although it is the task of the educator or the educational curator to create spaces for learning, reflection, and debate and work in the name of education, the responsibility for the sense of education created by a museum or art institution will never be theirs alone.

Education is not an activity or a sector within an institution, but a place of political co-responsibility in which we all act, willingly or not. So, the decisions, methodologies, actions, and practices carried out by a museum make up the set of pedagogies from which this museum operates and structures itself. Less or more visible, directly or subliminally, they are never impartial.

In this sense, for the museum to understand what it must unlearn, it must be able to look with critical care at the idealized self-image that it has historically constructed and, from there, review its institutional pedagogies from what bell hooks calls ‘love ethics’, that is, a different set of values to live by, in which power and domination are no longer possible methods.

X.

Questions like –

How to rethink museums when the number of femicides grows exponentially instead of decreasing?

How to rethink museums in the face of the social epidemic of parental abandonment in the world?

How to rethink museums when the rate of children living below the poverty line is 40 percent?

How to rethink museums when hunger is a reality in the homes of thousands of people?

How to rethink museums in the face of the fact that prisons continue to exist?

How to rethink museums in the face of the unbridled medicalization of life?

How to rethink museums without falling into reactive micropolitics?

How to rethink museums when their pro-environment speeches and public programs are sponsored by companies that expropriate and exploit land and lives somewhere on the other side of the world?

How to rethink museums without falling into moral precepts and convenient ethical parameters?

How can we rethink museums when the labour reforms that favour them seek to make the lives of those who work in them even more precarious?

How to rethink museums without rethinking the structural racism that shaped them and that guides their existence?

How to rethink museums beyond saving progressive rhetoric and missionary policies?

How to rethink museums when their collections are largely formed

from invasion and expropriation?

How to rethink museums when the theories and logics that structure them continue to be thought from the same places, bodies and voices for more than 500 years?

How can we rethink museums and not consider the role they play in the system of social, political, economic, and cultural domination?

How to rethink museums and not fall in models of cultural appropriation and epistemic extractivism?

How to rethink museums beyond the strange mixture between school and business?

How to rethink museums without persisting in the idea of progress?

How to rethink museums beyond the idea of utopia?

How to rethink museums beyond the aesthetics of empathy?

How to rethink museums beyond the logic of ‘satisfaction guaranteed’?

How to rethink museums without resorting to analogies?

How to rethink museums so that they stop teaching and make an effort to learn?

How to rethink museums as places where different subjectivities circulate, not just audiences and numbers?

How to rethink museums based on anti-colonial voices rather than post-colonial theories?

How to rethink museums beyond civilization theories?

How to rethink museums as non-saving devices?

How to rethink museums without making ‘historical reparation’ a public programme of four meetings?

How to rethink museums without rethinking the sense of education that structures and organizes them?

How to rethink museums beyond the ‘themes’ and the ‘agenda’?

How to rethink museums without rethinking the declarations, contracts, work hours, and the tickets?

How can we rethink museums without doing the exercise of transforming language?

How can we rethink museums and not asking ourselves why we continue to work and believe in them?

How to rethink museums as anti-racist organizations?

How to rethink the museum considering that its historical debt is unpayable?

How to rethink museums without falling into the desire to end them?

How (not) to rethink museums in the face of all this?23

– need to be understood and answered structurally, that is, from the guts.

XI.

If the museum really wants to invest in a review process, it needs to be willing to review itself epistemologically, that is, understanding itself not only as a space of historical memory, but as a historical figure – as a direct agent in the construction of a certain project of reason and, therefore, in the validation of the world as we know it. By assuming itself as an agent of this machinery, the museum will be able to better understand its political, economic, social, and cultural responsibility today.

In this process, it is important that the museum refuses the missionary logic of saving the world. Aside from being misleading, it serves no other purpose than to reinforce its own voice and benevolent self-image. The museum is not and has never been a neutral or passive figure. There is no other way to face this than by diving into its own entrails, analyzing the institutional pedagogies that structured it as a place of power. Otherwise, it may fall into the trap of thinking it is making historical reparation when in fact it is making epistemic extractivism.

In this sense, it is essential that the museum inhabit its vulnerabilities and accept itself as an unstable place – that is also ugly, bad, wrong, complex. It is necessary that it assumes its political responsibility in the face of the historical construction of the facts and learn to expose itself, that is, to leave from its position. Learning, more than teaching, can be a good methodology for this. Finally, it seems urgent that the museum reflect deeply on what it means to think and act in terms of an ‘agenda’ in a world whose politics is the aesthetics of the now, therefore, a world in which narratives and debates are constantly capitalized and/or aestheticized, and whose obsolescence is already programmed. So that personal narratives and historical debates do not become magic words within museums, it is necessary to understand and address them as the living processes they are, that is, as processes that were not produced to fit on their walls or galleries, nor in their agendas.24

XII.

Yes, the paradoxes are as innumerable as the imbrications. Here at the crossroads there is always a knife at one’s neck. What remains is to ask ourselves: Why do we produce what we produce, and for whom? How do we abandon our narcissistic power and, instead, let ourselves be affected by the Other – by the one, or by the us, that is not us – in order to generate, sustain, and embody, constitutionally transformative effects of dissonance, as Rolnik suggests?25 Against which ‘apocalypse’ are we really positioning ourselves? What kind of world do we want to be part of, after all?

XIII.

Because, as bell hooks says, ‘awakening to love can only happen if we let go of our obsession with power and domination.’26

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

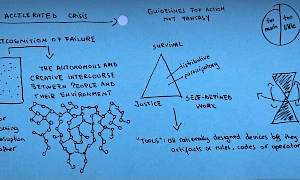

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

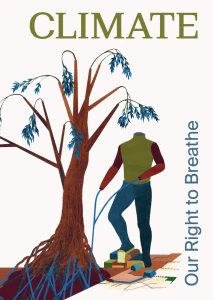

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

Related contributions and publications

-

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Settler Colonialism in Ungreen, Climate-Unfriendly Disguise and As a Tool for Genocide

May-Britt ÖhmanEN sv -

Beyond COP21: Collaborating with Indigenous People to Understand Climate Change and the Arctic

Candis Callison -

Theorising More-Than Human Collectives for Climate Change Action in Museums

Fiona R. Cameron -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

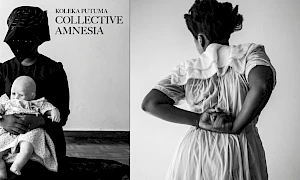

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand