Mass Student Protests in Serbia: The possibility of different social relations

As mass student protests challenge the status quo in Serbia, Europe has remained largely oblivious, and silent. Activists and cultural workers Marijana Cvetković and Vida Knežević describe the motivations, strategies and tactics behind this mass movement, and the ways in which the cultural sector is transforming itself. Based on the students powerful example and their use of direct-democratic methods, Cvetković and Knežević argue that 'there is an alternative' and 'it is right before our eyes'.

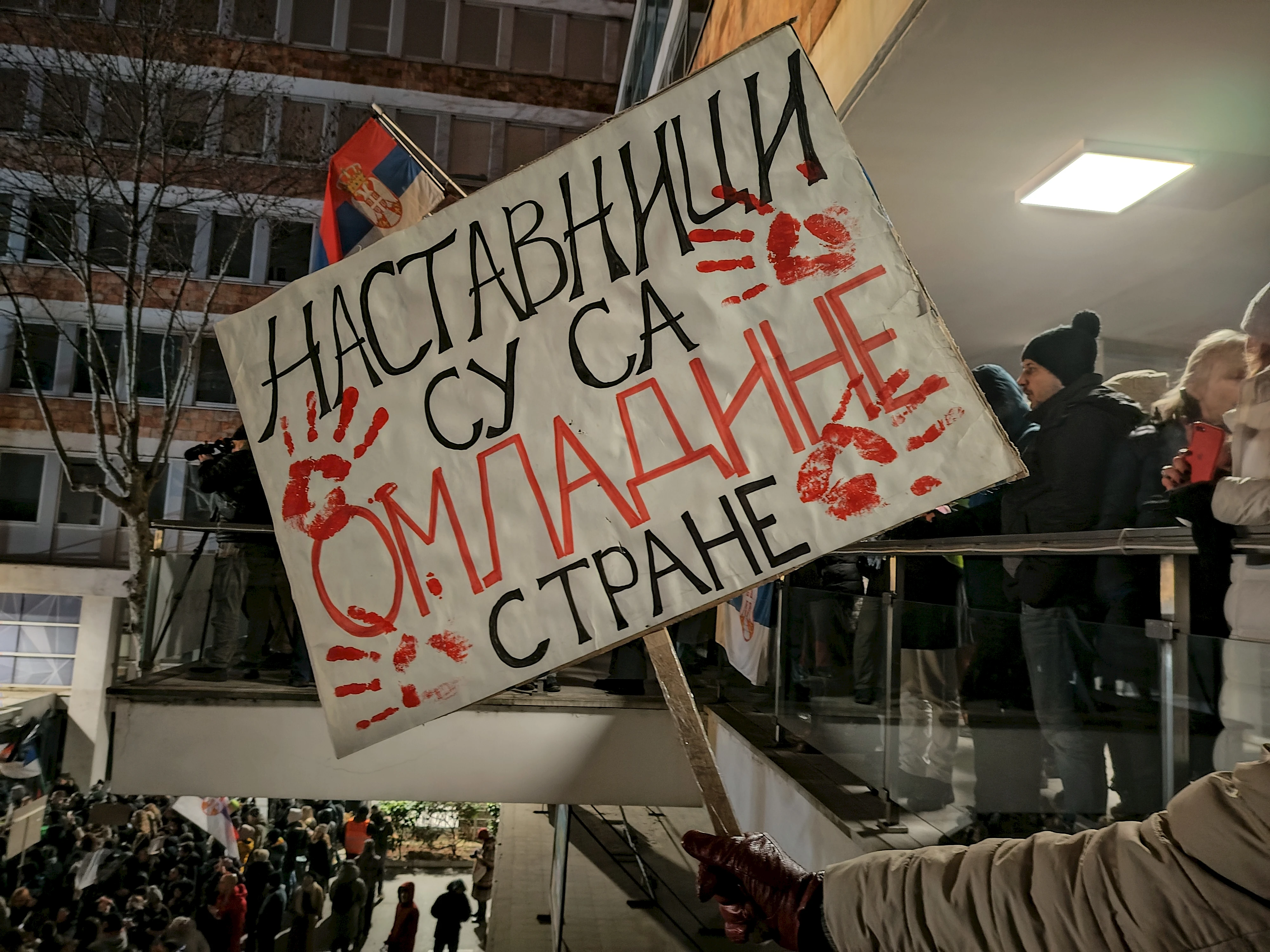

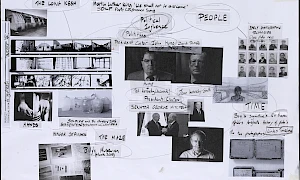

Mass student protests and blockades have been taking place in Serbia for the past three months, triggered by attacks and violence committed against students during ‘Your Hands Are Bloody’ and ‘Serbia, stop’, a series of civil protests initiated after the collapse of the canopy above the main entrance of the railway station building in Novi Sad on 1 November 2024 at 11.52 a.m.1 The incident resulted in the death of fifteen people, including a six-year-old child, while two others were seriously injured and permanently disabled. The entire state leadership is being blamed for the collapse of the canopy, which was ceremoniously inaugurated in July 2024, with demands for accountability regarding evident corruption and attempts to cover up the case.

In the four months following this event, Serbia has witnessed the largest student and worker protests in its recent history, with hundreds of thousands of people taking to the streets in cities and villages across the country. These protests have been fuelled by the outcomes and consequences of the twelve-year rule of the current president Aleksandar Vučić, and his Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), during which labour and social rights for the majority of working people have rapidly deteriorated. This period has been marked by the looting of public budgets, the collapse of public institutions and state-owned enterprises, crime, corruption, the sale and destruction of infrastructural facilities, and the demolition of cultural heritage sites.

Joint mass protest of students, workers and women, International Women's Day, 8 March, 2024. Photo: Lara Končar.

The ruling regime has significantly amplified the sociopolitical processes that have been unfolding in Serbia since the dissolution of Socialist Yugoslavia, the wars of the 1990s, and the widespread pauperization and privatization that persisted into the 2000s. These developments have been further accelerated by the imposition of neoliberal reforms. Tailored to Serbia’s position as a peripheral European country, this sort of capitalist system entails a regime of economic and political pressures that enable neocolonial relations, primarily in the form of cheap labour by workers disincentivized to fight for their fundamental rights. Brutal appropriation of natural and mineral resources and the granting of concessions over extensive systems (roads, airports and other transport infrastructure, land) and political support to the local comprador elite (who also profit from these processes) to the public detriment, are all outcomes of this regime. Concurrently, the entire society has been plunged into poverty, compelled to ‘accept’ inadequate living standards. The consequences of these economic and social policies are evident in the fact that Serbia is the country with the most pronounced social disparities in Europe.2

Amid the prevailing sociopolitical landscape, the ongoing mass student and civil protests have successfully catalysed a transformative ‘rupture’, as metaphorically articulated by the renowned author Arundhati Roy in connection with the global pandemic of 2020. Despite our relentless efforts to restore the ‘normality’ of the past, this ‘rupture’ has unveiled a ‘gateway to another world. And the readiness to fight for it.’3

For numerous artists and cultural workers, this ‘rupture’ has ushered in an intense period of self-organized practices, driven by social solidarity, resistance and a sense of shared struggles.

The political potential of the movement is reflected in the students’ push to expand the front lines, persistently urging other, predominantly atomized, social groups and sectors to (self-)organize and connect. Under the slogan commonly used by students, ‘Students in Blockade, Workers on Strike’, solidarity is ‘pumped up’ among students and workers, as well as for all other segments of society.

With the support of the student body, the first general strike and day of ‘widespread civil disobedience’ was 24 January 2025. Tens of thousands of citizens, students and secondary school pupils flooded the streets of Belgrade and other cities. The students’ appeal stated, ‘We will not work, we will not attend lectures, we will not do daily errands. We are taking freedom into our own hands. Your participation makes a difference.’ This appeal garnered a substantial public response, despite the escalating pressure of the ruling regime’s attempt to exert complete control over the entire public sector and its institutions, including the management of key representative unions. For a day, numerous small business owners, including grocers, restaurants, cafes, bookstores, craft shops and other establishments, closed their doors. Lawyers, trade unions representing cultural workers, theatres, a portion of the media and numerous professional associations also supported the suspension of work. Students were joined by pupils from various secondary schools and their parents, as well as by educators who suspended classes nationwide. In the interim, a call for a general strike was issued on 7 March, organized by students blocking faculties in Novi Sad. They urged citizens to cease work, refrain from shopping and avoid using hospitality services, public transportation, cinemas or theatres on that day, inviting them to join the students on the streets instead.

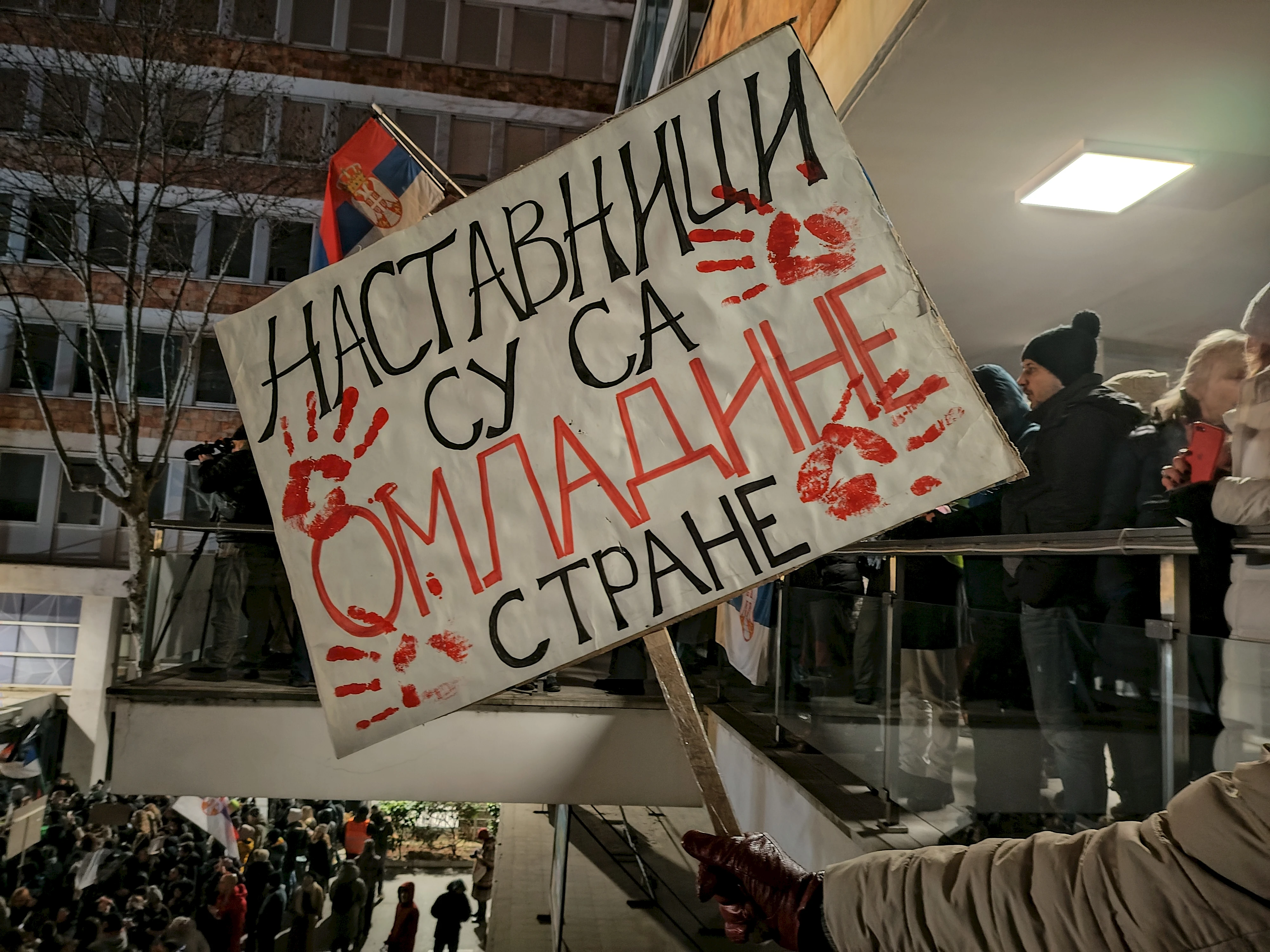

Despite tremendous pressure, threats of salary cuts and dismissals, and despite the teachers’ trade unions accepting the ruling regime’s offer intended to pacify them, school employees established new informal networks, such as the ‘Association of Schools on Strike’, through which they continued to support student demands while simultaneously articulating their own. Wave after wave of strikes within the education sector have persisted for the past year, flaring up in the autumn and intensifying in tandem with the student blockades. Having quickly recognized the significance of the educators’ struggle, the students unequivocally supported all the demands of education workers in their public appearances and announcements. They actively participated in their protest actions and gatherings and coordinated their actions with them. It is important to add that the vast majority of secondary schools in Serbia experienced school blockades and pupil plenums initiated primarily by final-year pupils, following the lead of university students. Initially, the pupils demonstrated solidarity with the students, and subsequently, inspired by this alliance, also extended their solidarity to their striking teachers. The final-year students were followed by other, younger, secondary school pupils, who, embarked on another, unforeseen trajectory of sociopolitical education: through practicing solidarity, togetherness, direct democracy, negotiation, and striking. Through this form of education, they gained a practical understanding and experiences of complex social processes that were merely lessons from textbooks in school programmes.

In response to the students’ emphasis, throughout their public appearances and announcements, on collaborative partnerships between students, pupils, parents, teachers and university professors, as well as all citizens, there has been a significant shift in public perception of the social role of education and education workers. Moreover, over the past four months, school reform has unofficially begun. This transformation has been achieved through the power of unity, solidarity, plenums, negotiations and mutual support among pupils, teachers and parents. In the process, a system of relationships and information has been established that has empowered individuals in education, even amid immense pressure, to feel that they are in control.

Mass Student Protests in Serbia 2024-2025. Photos: Vida Knezevic

‘All Power to the Plenums’: The spread of a mass student uprising

The initial blockade of an academic faculty commenced at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts (FDU) in Belgrade. This action transpired following the attack on faculty students and professors on 22 November 2024, while they were peacefully demonstrating to pay their respects to the victims of Novi Sad. The blockade began on 26 November because the police failed to respond to the students’ request to apprehend the attackers. Subsequently, the rebellion spread to encompass all public universities throughout Serbia.

A distinctive feature of the mass student protests is their organizational structure through plenums, a direct-democratic method of decision-making, involving all participating students, by a simple majority. The students’ choice of this form of political organization is neither coincidental nor historically unfounded.4 The organizing of faculty blockades is the foundation of their perseverance, mass mobilization, and political potential, enabling other social segments to join the fight. The students have effectively opened the door to self-organized practices ‘from below’: direct action and direct-democratic methods that were once neglected or confined to small, marginalized anarchist and radical left collectives. Today, the term ‘plenum’ holds real significance in Serbia, opening up a range of possibilities for radical, systemic social transformations as well as the political subjectivization of new generations who may be instrumental in implementing change.

This form of organization has allowed students to present an initially wide set of demands, subsequently condensed to an ideological minimum in order to establish a mass front of social support and struggle. Recognizing the ideological differences that have been hindering political activity in Serbia for decades (as a result of the regime’s demonization of opposition and even political engagement itself), the student plenums have maintained a stance of noncooperation and disengagement with all political parties and organizations from the outset. The students continue to assert that their struggle is directed towards the realization of four fundamental demands, and the establishment of a social system in which ‘institutions fulfil their mandates’ as defined by the laws and the Constitution. With this strategy, the students have effectively neutralized the potency of the right-wing topics and prominent figures that have been tainting political and social discourse in Serbia since the end of the 1980s. At public student and civil demonstrations, issues such as Kosovo, Serbian nationalism, the ‘endangerment of the Serbian people’ and religious fundamentalism are less prominent. This shift has resulted in right-wing parties falling silent. They are absent from media outlets and public spaces, and there is declining public interest in their views – in other words, no one seeks their opinion.

Instead of drawing inspiration from the mass student protests that occurred during the 1990s, which were predominantly organized in a parliamentary manner (adhering to the principles of representative democracy) and featured recognizable student leaders (typically embodied in dominant male figures), the current students are inspired by the student protests from the second half of the 2000s. These include the 2006 student protests in Belgrade, which featured the slogan ‘Faculty Blockade: Knowledge Is Not a Commodity’ and resulted in the publication of the manual A Short Guide to Student Self-Organization, and the 2009 Zagreb protests, whose experiences and lessons were documented in The Blockade Cookbook. Over the past three months, the student manual has undoubtedly become the most widely read book among students participating in the blockade, providing comprehensive information on horizontal student organization structured around three fundamental bodies: the plenum, working groups and attendants.

As the governing body, the plenum of each faculty establishes its own set of specific rules of conduct and determines the working groups that subsequently assume responsibilities such as security, housekeeping and hygiene, strategy, goal development and communication, as well as various public actions. The attendants’ function is paramount in ensuring the implementation of protests and other activities. Their mass organization and discipline serve as a valuable lesson not only for the political opposition, but also for trade unions and broader society, demonstrating the potential for effective collective action through solidarity and unwavering determination in pursuing one’s struggles. The desire for justice, expressed as a call for institutions to uphold the law and ‘do their job’, has become a powerful motivator for thousands of Serbians. There is widespread public support for students, including donations of food and essential equipment to the blockaded faculties. Additionally, along their marches the students have been met with overwhelming receptions in numerous villages and cities, liberating residents from fear, anger, depression and political apathy. These encounters have led to cathartic experiences that foster (political) awareness and subjectivization among individuals who, for decades, had internalized the sense of being deprived of their voice (and right to vote).Recent research supports this notion, revealing that approximately 80 percent of Serbian citizens support most student demands, and 64 percent express support for the ongoing protests, in which a full third of the population has actively participated.5

‘Students, Workers, Peasants and Artists – A Single Struggle’: The implications of the student uprising for the cultural sector

As ‘the student perspective’ highlights the dysfunction of the general system and its institutions in Serbia, it also illuminates the systemic weaknesses of the cultural institutions that, for decades, have been on the verge of functioning, so to speak, due to the ‘state of emergency’. In recent decades, the Serbian cultural landscape has been characterized by a profound disconnect between public cultural institutions and the creators of culture themselves, including artists and cultural workers within those institutions, as well as those undertaking various self-organized initiatives and independent cultural and artistic practices. Public cultural policies often obscure the true state of affairs, failing to identify critical issues that call for attention, or potent resources that require investment. Furthermore, an atmosphere of division and mistrust, particularly between the public sector and the independent cultural scene, has been first fostered and then nurtured by decision makers for an extended period. Additionally, the cultural sector in Serbia faces significant challenges in terms of financial, spatial and other resources, alongside concerns about the potential loss of hard-earned funding (and privileges), due to a tendentious misallocation of substantial funds to government-aligned structures and projects.

The impossibility of addressing these issues in this domain within the existing system of relations has led to pervasive decline in cultural life over the last fifteen years or more. The hierarchical decision-making and partocratic6 governance in place hinder pluralism in politics and democratic dialogue on critical matters. This governance structure is predicated on the exclusive control and implementation of a single dominant sociopolitical discourse, a system that closely resembles relations of production characterized by private ownership, while the public sector undergoes a gradual reduction and neutralization as a social factor. Consequently, cultural-institutional actors whose resources, finances, freedom of speech and labour are progressively curtailed, leading to a loss of autonomy and inability to determine the programmes they produce and present, are rendered incapable of defending these institutions.

This state of affairs has further exposed the class inequities within the sector and revealed the extent and the consequences of the catastrophically articulated and even more poorly implemented state cultural policies, which have left many on the brink of financial ruin. Unacknowledged and invisible, these practitioners have long since become ‘the dark matter’ of the system, as defined by artist and theorist Gregory Sholette.7

Liberated Students Cultural Center in Belgrade. Photos: Knežević Strika.

Student Cultural Centre and Cultural Centre of Belgrade: ‘The Student Cultural Centre for Students!’ and ‘Culture for All’

The prelude to the rebellion and blockades in the cultural sphere began in December 2024, when public theatres in Belgrade, Novi Sad and other cities staged a powerful symbolic gesture by ending their performances with bloodied hands. This action went on for several weeks and was followed by strikes and work stoppages, with actors and other employees of these theatres expressing unequivocal support for the students. Subsequently, large orchestras, including the Belgrade Philharmonic Orchestra, the National Theatre Orchestra and the Serbian National Theatre, also joined the cause.

In early February 2025, while students were preparing for the occupation of the Student Cultural Centre (SKC) in Belgrade, once a vital institution for youth and student culture, an informal initiative titled ‘Culture in Blockade’ (hereafter also ‘the initiative’) was launched. The initiative ‘liberated’ the Cultural Centre of Belgrade (KCB), one of the city’s vital central institutions, by taking over its cinema hall (DKC), and organizing daily plenums.

The objective of the self-organized students who occupied the SKC was to liberate the institution towards critical thinking and self-education, fostering new encounters and exchanges of ideas. As they themselves emphasized, the SKC should serve as ‘a welcoming space we happily return to and which is an integral part of our lives’. Originally, the SKC was one of numerous youth cultural centres established during the socialist self-management period in Yugoslavia, a direct result of the famous student protests that took place in 1968. Over the past few decades, the SKC has been transformed into an institution of the national neoliberal capitalist state. During the 1990s and the subsequent neoliberal transformations of the 2000s, an entire array of student and youth institutions, which had, in the former Yugoslavia, served as platforms for young individuals to engage in the creation of various cultural, artistic and educational content, became gradually detached from the fundamental principles upon which they were established. This trend included but was not limited to the SKC, which was not only subjected to non-transparent and irregular management practices but also struggled with the commercialization of its infrastructure and programmatic content. Situated in the heart of Belgrade, this significant youth institution began its operations two years after the demonstrations of ’68, and at this pivotal moment its management was entrusted to the University of Belgrade. In 1993, a legislative amendment resulted in the SKC’s separation from the university and its direct administration by the Ministry of Education. This shift symbolically and administratively alienated the institution from its intended constituencies, effectively removing not only the SKC’s management and decision-making processes, but also its access and use, as well as the cultivation and development of student culture, from the purview of students and faculty. One of the primary objectives of the ongoing student blockade is to restore the SKC’s affiliation with the university, thereby empowering the majority of students to participate in decision-making processes with the assistance of their professors. This request was submitted to the Ministry of Education shortly after the establishment of the SKC blockade in February of this year.

Inspired by the students’ protests, the informal ‘Culture in Blockade’ initiative is also organized on the principles of direct democracy and plenum, and is open to all cultural workers, independent artists, members of art associations and employees of public cultural institutions. From the outset, the initiative has supported the students’ blockades and advocated for their demands, while expanding the social front of the struggle in solidarity with educators, farmers and workers in other sectors, thereby raising the question of the position and function of cultural institutions and the need for radical transformation.

It is possible that this change might serve as a catalyst for a profound re-evaluation of cultural institutions and the role of art in fostering potentially different (more equitable) social structures, not least, a radical transformation in the organization of workers within the cultural sector and a critical examination of both content and production methods. It could also lead to the emergence of a new class antagonism and new avenues for struggle through artistic and political means – precisely the kinds of practices that Walter Benjamin ascribed to the role of intellectuals engaged in social struggles, their position relative to the proletariat, and the manner in which they are to be organized.8 From the Paris Commune to the present, such connections between artistic and political struggles have been and continue to be integral components of the art of the Left, and are still evident today. These critical artistic practices authentically raise awareness of the ineffectiveness of addressing political issues solely through aesthetic means.

The history of distinctive encounters between Yugoslav art and politics during the long twentieth century continues to be etched in collective memory. Notably, this includes the interwar revolutionary social movement that emerged from the convergence of workers’, students’, women’s and artists’ fronts, under the leadership of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. This movement played a pivotal political role in shaping new, socialist social relations, following World War II. Despite the strong revisionist tendencies imposed ‘from above’, transgenerational memories persist of the socialist self-management policies that were practiced and experienced. Not confined to specific institutions, these policies permeated various aspects of our lives, including in schools, workplaces, local communities and other forms of collective existence. The integration of this knowledge of previous generations into the fabric of our society enables today’s students to instinctively, affectively, spontaneously and intuitively comprehend the power of collective action.

In response to the ‘Culture in Blockade’ general strike, numerous cultural institutions at which work had been suspended were subjected to attacks by the authorities, including inspection visits and intimidation by the Ministry of Culture. The initiative has continued to organize protests in front of the Ministry, with clear demands. Of these, key demands include ensuring accessible culture for all by securing sustainable financing for the cultural sector, allocating at least 1.5 percent of the national budget and 6 percent of the local budget to be fairly distributed via a process including the full participation of all relevant actors and entities. Further demands include the release of complete documentation regarding the EXPO 2027 project,9 and a halt to ‘investment urbanism’ and the destruction of cultural heritage in Serbia, citing current examples of illegal and unconstitutional decisions such as revoking the permanent cultural heritage status of the Yugoslav Ministry of Defence Building, and the case of the Belgrade Fair complex.10

In a public explanation, the initiative clarified that the KCB had been ‘liberated’ rather than occupied. This distinction underscores that the status of a public cultural institution is that of a shared resource, serving all citizens as a legitimate platform for societal engagement. The insistence on the concept of ‘liberation’ implies an awareness that the goal of all struggles in various segments of society over the past few months has been just that: liberation. In this case, the initiative specified, the forces from which the KCB has been liberated include ‘individual interests, capitalistic exploitation, nepotism, partocratic employment, exclusive market practices, and corruption’.11

Mass student protests in Serbia 2024-25. Photos: Lara Končar

There is an alternative, it is right before our eyes

Since the protests began, waves of optimism and hope have continued to emerge, helping to unite, connect, influence and effect changes within the social system, which, in Serbia, is underpinned by nationalist policies and the privatization of all social resources. The result has been extreme class and economic stratification, dividing society into the comprador bourgeoisie, the silenced middle class, and the impoverished workers. Furthermore, values such as solidarity, togetherness and compassion have been effectively neutralized. The messages and actions of the student groups, operating as a united, cohesive and disciplined social force, could not fail to get the attention of those groups that have been opposing the regime for years, albeit with less success: educators, farmers, cultural workers from the independent cultural scene, environmental justice fighters and activists (against, for example, the privatization of mineral resources and lithium mining, the pollution of air and waterways, etc.), and unions in the public and other sectors, such as electric power production, where corruption and abuse of public resources have become evident. The students, for their part, recognizing all these fights, organized in support and formulated direct messages to encourage those groups to continue their struggle. Emerging from these initial alliances, the fight has gradually expanded to include other citizens who joined the protests and who, while they shared the students’ demands, also brought demands of their own that were significant to their communities. Through this alliance, these citizens’ demands too gained further momentum. A widespread feeling of liberation from the fear of the oppressive influence of authorities and their coercive tactics of ‘ruling’ has permeated the entire nation. In almost every municipality, for several weeks, daily protests have continued (and continue) to be organized, simultaneously addressing local concerns and fostering a sense of community, solidarity and faith in the potential for collective social transformation.

That these cohesive social processes are propelled by determination, resistance and struggle for systemic change makes the current events a particularly sensitive topic in relation to the policies of the European Union, the United States, China and Russia towards Serbia. All of these political entities share support for the current Serbian regime, albeit in their own ways and for their own interests, while being declaratively in favour of peaceful negotiations and against violence. The European administration, for one, appears to have been caught unprepared by the students’ tactics and strategies, and equally apprehensive about questioning the adequacy and efficacy of representative democracy.12 Furthermore, the EU seems more concerned with the realization of its economic and political interests than the aspiration of the Serbian people to liberate themselves from the corrupt regime.13 Yet, the students’ demand, and that of a growing number of other social actors, for the introduction into society of plenum organization and direct democracy has emerged as the most significant achievement of these protests. Through, and for, its consistent application and ongoing critical self-examination, a new generation of conscious and active citizens has come to be recognized. This generation emerges as one that has successfully overcome numerous constitutive elements of the neoliberal system, such as competition, privatization, individualism and uneven power relations among people and nations.

Underpinned by the Thatcherite paradigm that posits the nonexistence of society and the primacy of individuals and their private interests, the systemic erosion of the social fabric has been imposed upon us since the 1980s as an unquestioned doctrine without an alternative. However, a reaction to this ideology is re-emerging, and, like a boomerang thrown from a peripheral capitalist colony to today’s Europe, it comes with a powerful message: there is an alternative, it exists, and it is unfolding before your eyes.

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

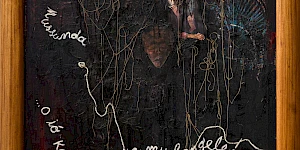

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

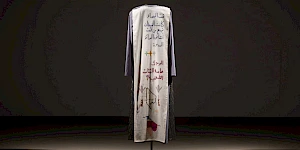

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

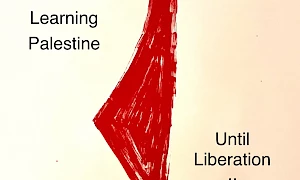

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials