Poetics and Operations

This conversation between artist Otobong Nkanga and curator Maya Tounta builds on the pair’s contributuion to Climate Forum III: Towards Change Practices: Poetics and Operations. The exchange moves between Nkanga’s studio in Antwerp, the farm co-run with her brother Peter and Akwa Ibom, the space she co-founded with Tounta in 2019. Nkanga’s poetry and close readings of images and objects serve as entry points to dwell on questions of transformation, failure, regeneration, repair and change.

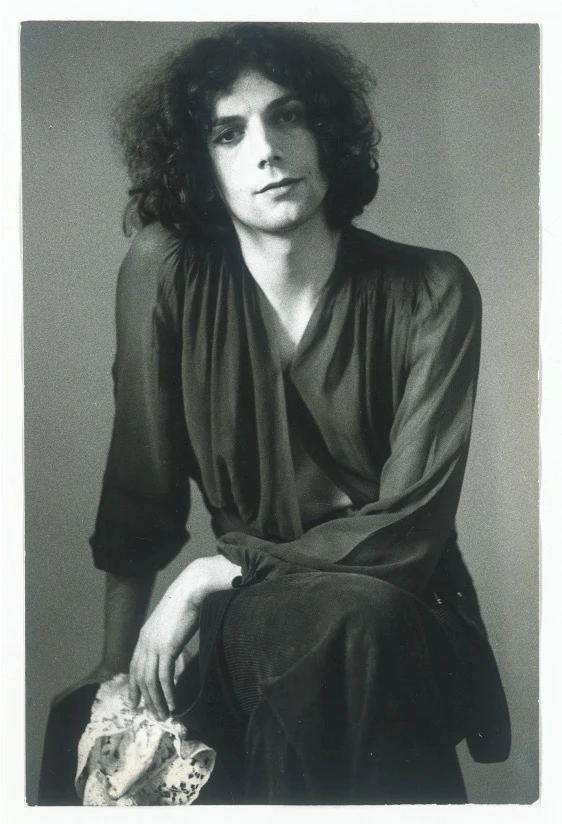

Otobong Nkanga: Whose crisis is this? (2013) addresses the multiple life forms and entities living on this planet and their interactions with humans. Today, many things are cracking. The landscape is shifting. We are moving through the world differently. I wanted to think about a relationship to resources and the things that give life to other life forms. What does that mean for people that are in relation to natural resources? Human extraction has meant that those who take ownership of resources deny the possibility of the commons.

Whose crisis is this?, 2013 acrylic on paper. Courtesy the artist

In this drawing, humans extract from other humans, while trees are being sucked dry of water and minerals.

Burning Tongues

Taste the salty skin

Tame the sultry

Burning tongues

Born from a tear:

Looking for some terms

That could unite us

Like a glorious choir in sync

Solid Manoeuvres, 2015, performance – duration 1 hour, Thursday December 17, 2015, performed by Otobong Nkanga, 'Bruises and Lustre', M HKA, Antwerp. Photo M HKA, courtesy the artist

Solid Manoeuvres, 2015, acrylic, Forex, makeup, tar, various metals, vermiculite, 'Bruises and Lustre', M HKA, Antwerp. Photo M HKA, courtesy the artist

I will start with an image of an anthill. Now think of the way we, as humans, make holes within spaces, extract, and then turn what is extracted into other forms. Like a skyscraper: imagine the holes and materials required to build skyscrapers, or phones. The performance and sculptural piece Solid Manoeuvres (2015–20) speaks to that process.

Performance allows for an expanded form of storytelling in which we relate to materials through, inside and around the body. The materials in the sculpture – metallic, tars, acrylic – are all transformed from minerals in the ground to what’s in the sculpture itself: the heavy sand, salt and make-up that are part of everyday life.

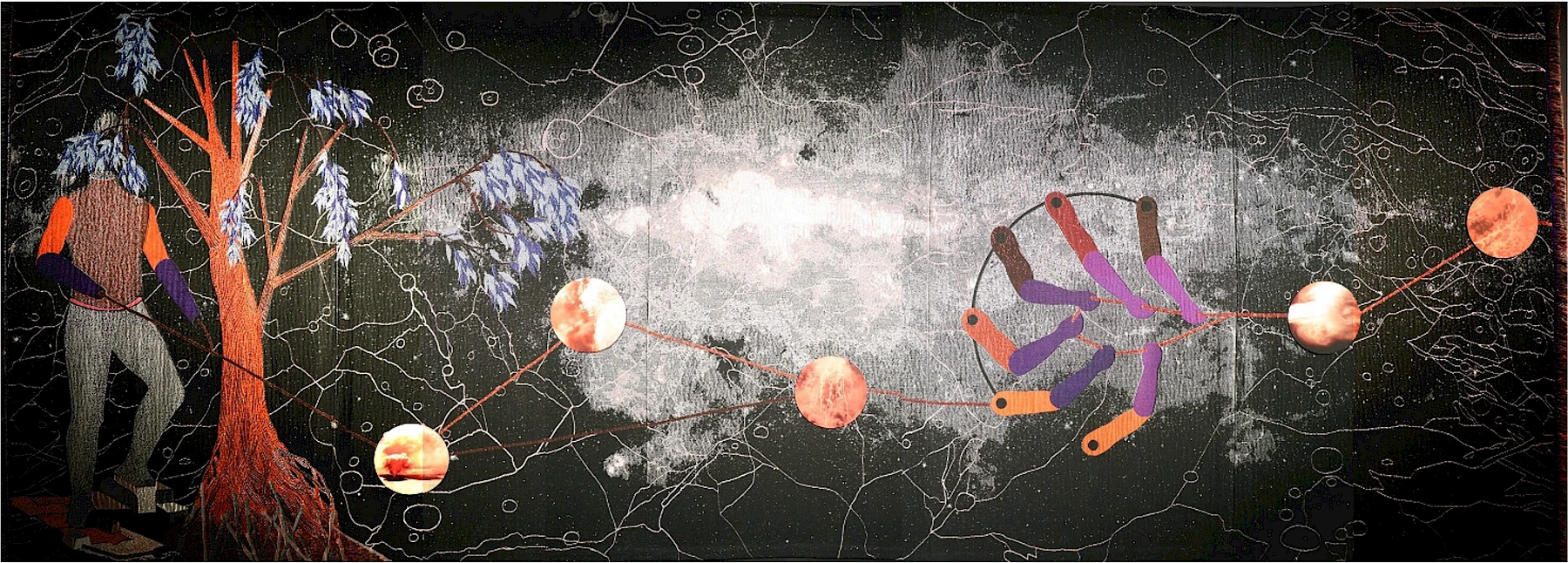

Carved to Flow, Preliminary Recipe for a Support System, 2016-17, digital drawing, collage and acrylic on paper. Courtesy the artist

The works presented at Portikus in Frankfurt, addressing extraction, were pivotal for Carved to Flow (2016–), which I started thinking about in 2016. I was not only thinking about the things where holes are made, let’s say, but how that affects places. I call them places of obscurity. Those places where things are taken out from the land, where the livelihoods of people also change and the landscape and ecology of a place changes. Most of the time we do not hear much about these places. I was moved to think: What does it mean to work from a place and not only think of the holes that are there, but to imagine and create structures that could be support systems for places of extraction? I wanted to create something that could be generative and that could be taken care of, something that would allow you to connect with the life – the flora, fauna and other life forms in a place.

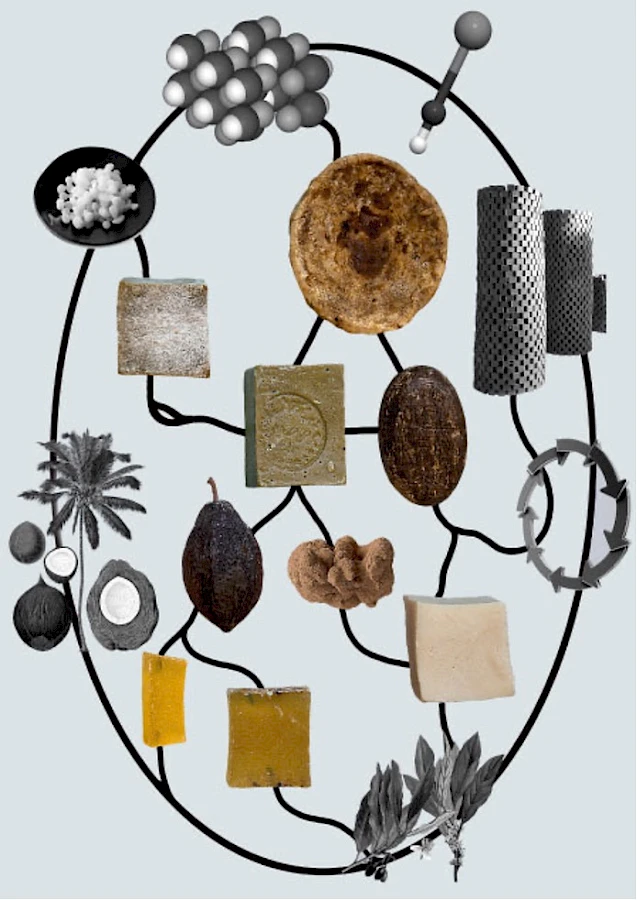

In Carved to Flow I started to work with soap. This was the first drawing reflecting on places that feed the world – if we think of Southern Europe or North Africa, West Africa, the Middle East – with the oils and materials that come from these places. And at the same time, these places are going through wars, intense ecological crises, mass migration, political and social shifts. And that’s where the idea of the soaps began.

Last Year June

I dreamt of you early in the morning early after mourning

I dreamt that you slightly foaming lightly with a smell

I was nervous when I was invited for documenta in 2016. I wanted to make work – or embark on a process – that was connected to different landscapes. The first idea for the project came from a dream about the smell of soap. I remember waking up at seven-thirty in the morning, and I turned around to my husband and said, ‘Oh my God, I know what I’m going to do for documenta’. That clarity was based on the project being in two places, in Athens but also in Kassel, and reflecting on how many plant-based oils are found in the Mediterranean region, but also in many territories including Nigeria, where I come from. And that’s where we started from. So this was 2017, when I met Maya Tounta who I have worked with since, and with whom I co-founded a space in Athens.

Carved to Flow: Laboratory, soapmaking session with Otobong Nkanga and Evi Lachana, documenta 14, Athens, Greece, 2017. Courtesy the artist

Maya Tounta: Up until that point, Otobong, you had worked with performance, installation, sculpture, drawing and painting. This was the first time you moved beyond those formats and the work became more difficult to categorize. The laboratory in Athens was opened up during documenta as an installation space: as a sculpture, but also as a workspace. There were many aspects of this work which were invisible to the public but were crucial to how it functioned. One was the development of a ‘product’ that would support and finance other endeavours independent of Carved to Flow.

The project wasn’t conceived as a finalized idea that was then executed. Rather, you began with documenta, and then slowly things started to appear in terms of what made sense and how it should develop. And it’s still evolving.

ON: In Athens, we needed a space where we could have a laboratory. And of course, a museum structure could not offer the kinds of things that Carved to Flow needed. We found a space in Kallithea but where we had to build everything: new floors, new lights, new windows. This became the workshop where we could invite people to test our prototypes for the soaps, but also a space for rest and conversation.

Carved to Flow: Laboratory, installation view, documenta 14, Athens, Greece, 2017. Courtesy the artist

In 2016 I met different people – Maya, but also Evie Lachanae, a botanist. Evie knew how to think about the business model of the project but also to choose products that were ethically sourced, how to work within a circular economy of materials – all things that were important to me. With Maya we thought through the operations of the project, the production and presentation of the work as well as formulating the language around the exhibition. Maya curated the public programme. She sees and describes the project in very expansive terms, not only who is involved in the project itself but in relation to the realities of today.

MT: We had to understand, together, what this process of making soap entailed, including its history. In Greek villages in the 1960s, it was quite common to collect leftover fat and cooking oils to produce soap for the whole community. It was first and foremost a social process, one that embodied a circular economy through the recycling of material. Otobong researched similar practices in other places, including in West Africa and, of course, in Aleppo, Syria.

It was important to bring other people into the work in order to understand what kinds of extensions cold-process soap had, how it persisted and survived and what this revealed about similar products. One perspective was that of ritual in the act of production, which for Otobong became a way to consider what kind of life a product originates in and reproduces; whether it is made in a commercial setting or in a personal, intimate environment. What are the elements involved that are not, strictly speaking, part of production itself?

We started looking at things that might seem remote from the process. For example, the poet CAConrad had, for many years, devised rituals aimed in part at deconditioning himself from everyday consumption. For instance, he would go to the parking lots of large supermarkets in the US, sleep in his car, and then write poems informed by that experience. Another example he shared in a workshop, though I’m not sure he ever actually performed it, involved standing behind the door of his apartment with one leg in a bucket of water while looking through the peephole. The point, I think, was to enter an experiential process that disrupted a capitalist mentality centred on maximizing time.

The question of alternative valuation within an economic process was central to the work. It shaped not only the soap recipes but also the broader process: with whom the soap was produced, and where. It actively informed decisions that did not always make sense financially but spoke to other value systems the work sought to explore, raising the oblique question of whether these decisions could also be felt in the soap itself or in the work as a whole.

Fernando Garcia Dory at the Carved to Flow: Laboratory, documenta 14, Athens, Greece, June 17 2017, programme curator: Maya Tounta. Courtesy the artist

Otobong had a really beautiful talk with Erik Van Buuren who researches circular economics. Fernando Garcia Dory, who works with agroecology in his practice, spoke in the space.

Mould

Eight meet in a melting pot

fifty five degrees perfect hot

sign a pact to form a solid block

bound by lye and blood

ON: Most of these poems were written in the development of the project. So, if we made the soap at a 55°-hot perfect temperature, it created a certain form for the soap, or type of texture.

Olive tree at the Vis Olivaie soapmaking laboratory in Kamalata Greece, where O8 Blackstone was produced, as seen during a 2017 research visit.

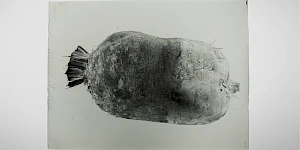

MT: O8 Black Stone was the core of the work. It is impractical as a product – it relies on oils from several geographies, meaning it’s not cost-efficient, yet it is the best soap I’ve ever tried. By that stage, which must have been a few months before the opening, there was a recipe in mind, but we didn’t know who could produce it in large quantities, and Otobong wanted it to be produced locally. We began travelling across Greece to meet different producers – amateurs, businesses and others – who were each given the same recipe.

The image you’re seeing is from the Peloponnese, where we met Vis Olivae. They had just started making soap, purely for the love of it. They had set up a small workshop in their basement while both were working full-time at a nearby hospital. Their passion was real, especially for using oil from Kalamata. Once we met them, it was an immediate fit for the project.

ON: We had met a company that was making soaps for boutique hotels in Crete and we knew from the way they were working that it would not work. Later on, we met a company that mass produces soap. When we went to visit the company, we learnt they were working with a mix of different chemicals, even though they talked about using sustainable materials. When we put all the soaps together, we realised that you could actually feel and see when something is alive and when something is dead. And this shrivelled soap that came out of Athens had no life. We were shocked. We wondered how two formulas can produce such different things. The soap from Vis Olivae was alive. You could smell it. There was a flavour and texture to it with this marbley effect. And when you used it, it was amazing. But at the same time, it was the most expensive.

A funny thing that happened when we visited the maker of Vis Olivae. He has beautiful olive trees that are over 100 years old. I remember coming out of his space, hugging one of the trees and talking to it. At the time I did not know that his wife had seen me. Later on, I received a letter from him written in Greek saying, ‘I heard that you hugged my tree’, and that he wanted to sponsor the project. And actually with his proposition he was the cheapest option. The tree helped me or helped us do this project. It’s always important to acknowledge that there are other entities working with you or creating a kind of passage for things to happen.

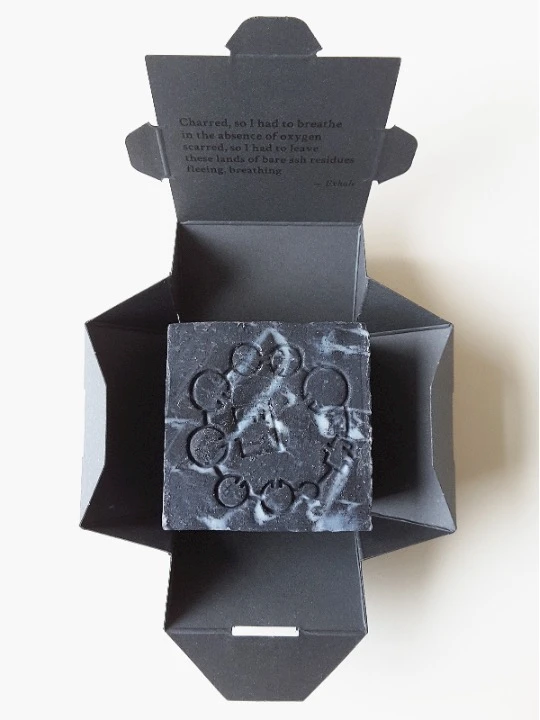

When we made the soap we made nine or ten prototypes, some containing seeds, olive seeds, cherry seeds; some of them containing chamomiles, indigo, and some just with earth. We were thinking of different geographies and what it meant to be able to use different materials in the soap. The one we chose for the project contains charcoal. It has seven oils and butters coming from the Mediterranean region, the Middle East and North Africa. The soap itself is a sculptural work that contains nutrients: it brings together different places of care, but also, through the charcoal, speaks to an absence of oxygen and what is burnt.

Exhale

Charred, so I hate to breathe

in the absence of oxygen

scarred, so I had to leave

these lands of bare ash residues

fleeing, breathing

Making the work, I reflected on what it means to be able to breathe in a landscape, in a place where the landscape is charred; in a place that has been affected by war, where there are droughts, water scarcity, where the elements that you lived with, that you were born with, become scarce. What does that mean in relation to renegotiating the landscape that you have to continue working in? What does it mean to migrate and to leave a place that you were born in, that your ancestors have invested in and all of a sudden it becomes alien to you? What does it mean in relation to the breathability of a space? And in relation to its economy, in relation to its ecology, in relation to its materials, in relation to storytelling. There’s so many things you consider that make a place breathable. Once that starts cracking, once that is affected by internal and external factors, how does one still find a way to relate to it? When we’re thinking of migration or the movement of people from a place, it’s not always a simple choice to leave a place that you know and to go to a place of uncertainty. The soap is a way of thinking of the relationship to charcoal, to organic matter, once we feel burned by a place – and of being able to breathe within that landscape.

O8 Blackstone, 2017. Courtesy the artist

With Carved to Flow we produced about 15,000 bars of soap. But we also had to think about transportation, distribution and legal questions. It was important to find the right language to talk about the soap as an art work, not a product. I remember the lawyer saying you would have to pay 19 percent tax on all the soap. And I said no, as an artwork you pay 7 percent tax, but how do you convince the tax authorities of that? The legal advice helped us understand how the work should be presented within the context of the exhibition.

MT: Otobong set up a foundation in Brussels that was able to absorb profits and process them into funding, via the King Baudouin Foundation. The foundation functions almost like a bank, with a unique purpose: whatever comes in from a sale is converted directly into funding that can only be directed to another nonprofit. This financial model made the project possible.

Carved to Flow: Storage and Distribution, performance at Neue Galerie, documenta 14, Kassel, Germany, 2017

The performance in Kassel was the first iteration of selling the soap. Later on it was also available in shops and museums, for example, but the first iteration of selling the soap was through performances. This led to adjustments in the way that transaction was made. One was that people would have to listen to the performer talk about the project if they wanted to buy the soap, which a lot of people didn’t have the patience for. From this came the second decision to allow the performers to refuse to sell the soap. It was a significant consideration of how a transaction could happen – that maybe money and the desire to acquire something is not enough.

'Earth Workshop – Bee Houses', workshop led by Nuno Vasconcelos, Thomas Meyer (RATIBOR 14), and Cornelis Hemmer (Deutschland summit!) in the framework of Carved to Flow: Germination, October 16 and 30, 2020, as part of There's No Such Thing as Solid Ground, Gropius Bau, Berlin, Gemany, July 10 – December 13, 2020. Courtesy the artist

And then we go to germination, which is the third stage of the project, and that is ongoing. The image that you’re seeing now is from an educational programme that happened in Dakar at Raw Material. There have been various iterations of this programme.

ON: We also had one in Gropius Bau during Covid-19. We invited the architect Nuno Vasconcelos, and he stayed in Berlin for six months. This space was an open space where people could come and work with soil related to different regions and areas. We made a sculpture for bees. Everything here could be touched. We did events within the spaces in Gropius Bau, often involving artists and different forms of spatial practice. We also started a podcast where I worked with Sandrine Honliasso.

MT: I’m realising now that Carved to Flow operated like a think tank. It allowed us to be in relation to different practices: to learn from and with different research, like the podcast with Sandrine, or to foreground practices that were precursors to this way of thinking, like that of Newton Harrison with his wife Helen, who, at the Harrison Studio, are pioneers of environmental art in the US and have managed to help shape several policy changes related to ecology.

Beyond this, the two long-term investments of Carved to Flow are the farm set up in Akwa Ibom, which is Otobong’s patrimonial land in Nigeria, and Akwa Ibom in Athens, which borrows its name from Akwa Ibom in Nigeria and is a nonprofit art space. This evolved quite naturally from the time that Otobong and I spent together in Athens.

Carved to Flow Foundation land in Uyo, Akwa Ibon State Nigeria. Couresy Peter and Otobnh Nkanga

I had left Athens in 2007 and came back ten years later to work with Otobong. I had no real sense of what the contemporary art scene looked like in Greece at the time. Together, Otobong and I realised pretty quickly that there was a lot of work, especially from the 70s and 80s, that had not really received attention and had not been written about or shown. That was one of our initial reasons for creating a space in Athens: to address the lack of institutional support for practices that were being overlooked. We set up this space together with an open approach to the programme, working with living artists, more historical material, but also different formats, including a fashion show with the German designer Kostas Murkudis.

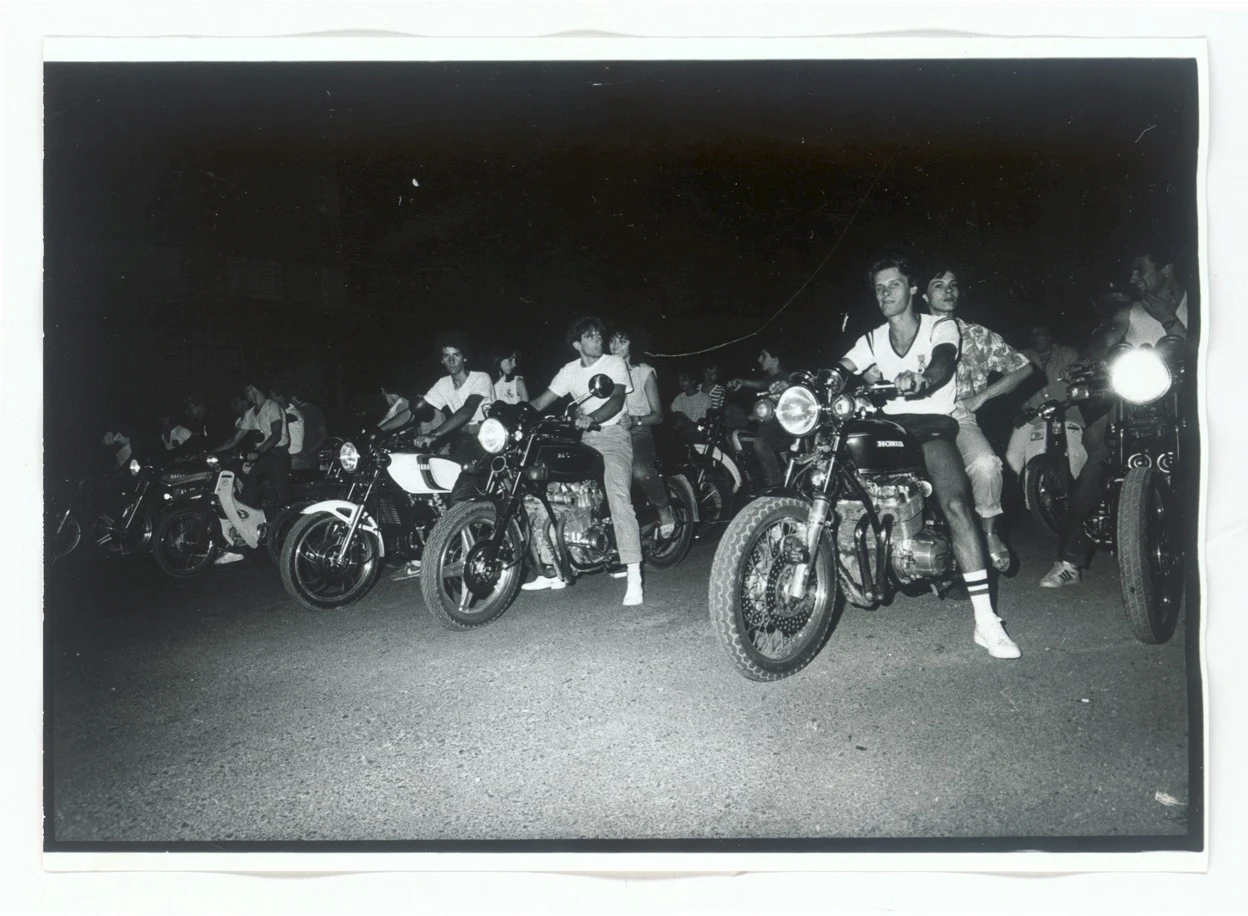

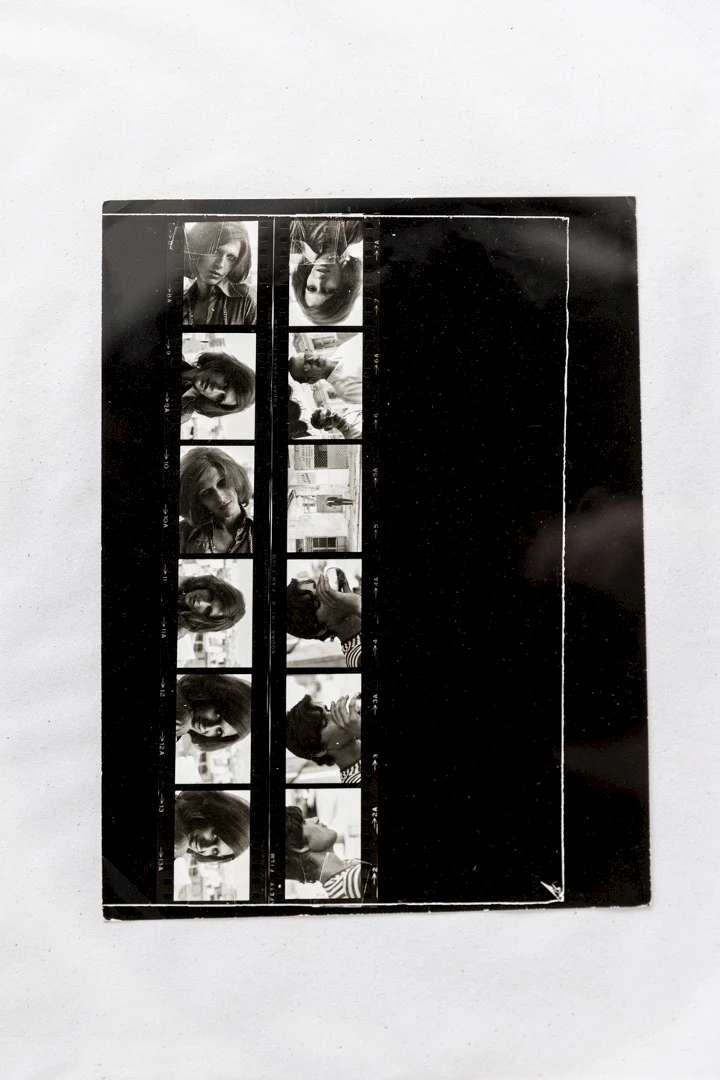

George Touskovasilis, Untitled, no date (c. 1980s). Courtesy Maya Tounta

George Touskovasilis, Untitled, 1981. Courtesy Maya Tounta

George Tourkovasilis, Untitled, 1973, Collection of Tasos Gkaintatzis

George Touskovasilis, Untitled, no date (c. 1970s). Courtesy Maya Tounta

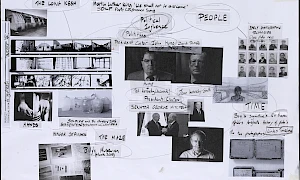

The most concrete, long-term engagement has ended up being the representation of two estates. One is that of the Greek photographer George Touskovasilis (1944–2021) who I met in 2020, and who had rarely exhibited during his lifetime. Touskovasilis had an incredible archive of images which varied from diaristic, personal images of his daily life to more documentary, sociological studies of specific subcultures in Greece. For example, there is one series taken after the military dictatorship in Greece, showing transgressive, illegal events like the motorcycle races that would happen in the outskirts of Greece. Touskovasilis had infiltrated and these photographs are the only documents that exist of that ever happening. He was also the main documentarian of the rock and punk music scenes in Athens and Thessaloniki. Touskovasilis documented his relationships with men and women. In Greece, nothing like that existed in sanctioned art history, let’s say. What we were able to do with Akwa Ibom, starting from the soap, was to make this work known. We did several exhibitions, and our next step is to translate one of his books into English to get the work known elsewhere.

Another figure we are working with is Christos Tzivelos, a sculptor who was active in the 80s who has also remained at the margins of the local canon. This is some of the work we are doing in terms of germinating back into the Athenian and Greek scene. I think it is an important contribution to try and change the narrative around different art histories.

Right Place

Our roots are anchored

To feed from this soil

The right place

To stay, to hold.

Home

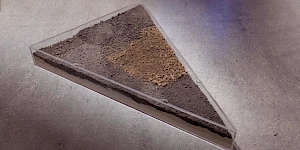

Unearthed – Sunlight, 2021, in collaboration with Martin Rauch, installation view third floor Kunsthaus Bregenz, 2021. Photo: Markus Tretter. © Otobong Nkanga, Kunsthaus Bregenz. Courtesy the artist

This is a work that I made in Bregenz. A lot of the pieces I make consider what it means to be able to create work within a space and related to a place. This is a soil from the Voralberg region whose economy is changing due to climate shifts. For a long time I was interested in going back to my father’s village, which I hadn’t visited since he died in 1981. The first time I went back was in 2018. When I went back, all of a sudden it all made sense. With that we started looking for the land in Akwa Ibom.

I found this land in my father’s village. We started getting one or two plots and now have about three hectares of land which my brother manages. He used to live in Abuja, the capital, and he decided to make his livelihood and live in Akwa Ibom. He started working with the soil, trying to revive certain soils, and changing its pH. Then he started planting trees: lemon trees, orange trees, palm trees, palm wine trees. There are many, many types of trees that we have.

Video shot at Akwa Ibom Foundation, 2024. Courtesy Otobong and Peter Nkanga

These are personal videos he has sent me. You can sense the aroma, it’s amazing. Queen of the night, flowering and bringing all of its extraordinary scent. This was a tree we planted about two years ago. My brother keeps sending me videos of things that are sprouting – a new flower, or if there’s a praying mantis or toad that he found at three in the morning, he sends videos.

Video shot at Akwa Ibom Foundation, 2024. Courtesy Otobong and Peter Nkanga

This was when I visited. It is behind the little house we built where NAME lives. We’re planting vegetables and things that local women could come and buy at a cheap rate and then they could go back into the market and sell to earn money. The farm is off-grid. We have solar panels, converters and a solar pump. And with that we’re able to charge people’s phones, charge their batteries, charge their computers at a very low rate. The money is used to pay people working on the land. We are able to pump water from the grounds and give people free water. We have a tap and from seven in the morning till seven in the evening, people are constantly taking water. It’s a way of practising the commons, but a way of generating an economy with our resources so we can have more workers, pay them, and also for people to generate an economy for themselves. We work with local plants with different timelines. Some come out in three months, some in six months, some nine months, and some trees will be ready in five years.

The way my brother thinks about planting is to place plants in the vicinity of other plants and to see how those plants work for each other. But also to think about what insects eat – and plant those plants around other plants, so the insects eat them first before eating our plants. Sometimes my brother would notice a whole exodus of millipedes and he would then let them pass through, planting things around them so they would not eat our plants. We don’t kill them, we actually allow them to pass through during different seasons. It’s an observation of the landscape and shifts the way we work in relation to other life forms moving through space.

Video shot at Akwa Ibom Foundation, 2024. Courtesy Otobong and Peter Nkanga

We’re still constructing and we’re constantly thinking about how we should work. Some land we’re thinking of as orchards and some other places we have local palm trees where we make our own oils. We have animals now – goats, a snail farm – and we’re creating a mushroom farm. People from the village are also working on the land. Carpenters, metal workers, all those people are part of building the whole space. It’s really interesting to see how things have developed since 2020.

Repair

She took the threads out

From the same cloth

Each thread would find its place

Interwoven to cover the hole

She would squint at every gap

Cut her breath to make it work

Time flies as fingers stiffen

Some gestures overlap to Repair the flaws over time

Landversation, conceived by Otobong Nkanga. Performed by Peter Webb, Shanghai, Sunday September 4, 2016. Courtesy the artist

With Akwa Inbom, the art space or the farm, we are constantly thinking about how to evolve. Do we need a space? Do we need the land this way? Do we have to shift? And so the space could be something else tomorrow. The project Landversation (2014–) was first done in Sao Paulo where I worked with an ecopsychologist, Peter Webb. He was later invited to Shanghai, Beirut and Bangladesh. The project involved conversations with people that are thinking about land in multiple ways: a homeless person, a permaculturist working with government on land policy, or those involved in water systems and infrastructures, for example. The conversations shift perspectives on different topics. For example, in one conversation we discussed how people might leave trash on the street not because they want it there, but because it serves to resist gentrification. Engaging with the economy and the politics of a place has shaped how I work with people, how I bring them together and negotiate their time, their labour, their way of getting involved. It’s a negotiation within all projects – if it’s a work in a museum or on the farm, with a painting or with a plant.

Double Plot

In a place between yesterday

Today and tomorrow

Paths form in slow motion

Visible traces melting away

That, which was solid

Flaking, aching, so many ragingIn a place between stillness

Fear and a slow meltdown

a new form grows

Visible only to the heart

Palpitating at the unknown

Flaking, aching, so many craving

Double Plot, 2018, woven textile with photography. Courtesy the artist

Once you’re negotiating with the landscape, and with people, there are a lot of emotions involved related to loss and anger. We’re seeing it also with places that are flooded. People are angry. We see that with people leaving places where they’re meant to stay, where they thought they will stay their whole lives. I am thinking through the emotional weight of landscapes, in relation to our histories, and ancestry. Those relations crystallize and ask for different ways to engage with the political landscape, the economy of a place and how we can relate to others and think of otherness, in which we bring in race, identity. But also the relationship to resistance and riot as in Double Plot (2018), produced for the Arte Mundi exhibition in Cardiff, which includes a series of images from different manifestations worldwide.

Manifest of Shifting Strains and Double Plot, 2018, National Museum Cardiff. Photo: Polly Thomas. Courtesy the artist

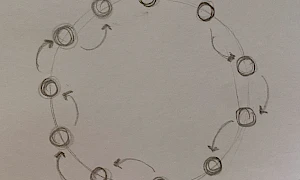

Shown next to this work was Manifest of Shifting Strains (2018). It is a circular form that contains different materials in different states. The work was looking at material and how it manifests through expansion, heat, rusting. For me, it’s necessary and generative to think through material in relation to politics and to the kind of upheavals that are taking place today. But also to think through these upheavals in relation to matter, the farm land, soil, the shift of acidity, what all of that means for many life forms. One is not separate from the other; rather, these are different forms of translation and visibility. I hope that makes sense.

I would like to end with this poem.

Future

The chains are formed

Linking stubborn bubbles

Of isolated worlds.

Will it stain or purge these ageing cells future.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

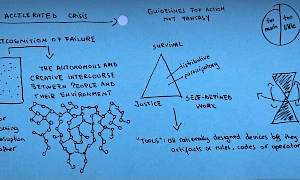

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

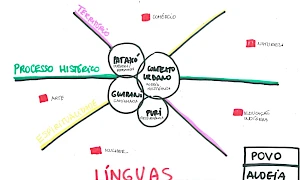

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations