The Library and the Massacre: A Novelist's Testimony on the Destruction of Libraries in the Gaza Strip

Novelist Yousri al-Ghoul recounts the complete destruction of libraries and access to literature for Palestinians in Gaza. It is described as ‘a systemic siege on books’ by the Israeli occupation, taking place over many years. The text was originally published by Institute for Palestine Studies and has been translated from Arabic by Jude Taha.

I often dreamed of living my life surrounded by books, moving from one to another – diving into a dictionary then exploring an encyclopedia, searching through indexes, and skimming through countless references each day. A page here would captivate me, a chapter there, perhaps a cover or an ending elsewhere. So, I decided to create a personal library in my home, one that would serve as a legacy for my children, my neighbors, and anyone in my community interested in reading and writing. My journey began during my university years when I started collecting books, particularly literary works, as I embarked on my path as a writer. Today, I practice narrative writing professionally and have published nine works, including short story collections and novels. Many of these have been translated into multiple languages and reprinted in several editions. My latest novel, Clothes That Miraculously Survived, published by the Arab Institute for Research and Publishing in Beirut, envisions a devastating massacre through the interplay of two narrative worlds: a shelter and the memoirs of a former Minister of Culture.

My home library continued to grow, as did libraries across other homes and throughout the city. Cultural life flourished, with cafés transforming into intellectual hubs. One such space was the Cordoba Culture, which I established eight years ago as a platform for intellectuals and literary figures in Gaza. Similarly, the Shaghaf Cultural Initiative brought together university writers, holding meetings at venues like the Palmera Restaurant, Cordoba Café, Masarat Center, and the House of Wisdom. At times, it felt as though Gaza itself had become a sanctuary – a vibrant center for intellectuals seeking their identity through colors and words. This was especially evident in the Shababeek for Contemporary Art, a venue showcasing art exhibitions by both established and emerging artists. These efforts were part of a larger mission: to create a legacy, to affirm an identity that the occupation seeks to erase from the collective memory of the world. Yet surely, those who paint or write poetry cannot be erased – so how could those who carry a rifle to fight?

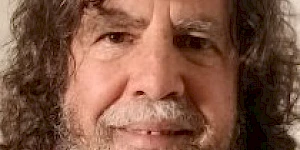

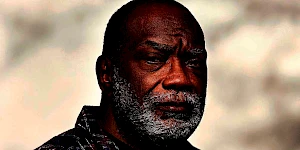

With children in the neighbourhood, Yousri al-Ghoul, Gaza City, July 2024

Several years ago, the occupation destroyed the National Library in Gaza City, razing its towering structure to the ground. With its destruction, the dream of creating a repository for both ancient and modern Palestinian works was obliterated. The site that once promised to preserve a rich cultural heritage became little more than a platform for displaying political party flags and leaders’ portraits. Yet, this cultural devastation was not an isolated incident; it was preceded by a systematic siege on books. While Palestinians had anticipated restrictions on food, fuel, and travel, few realized the occupation would also besiege their minds.

Books were imprisoned, their circulation banned, and their entry blocked.

The global silence on Palestinians’ right to read – a basic freedom enjoyed elsewhere – only deepened the loss. Libraries, stripped of vital collections, struggled to replace missing titles. The acquisition of new works, in an attempt to provide access to the latest knowledge and literary productions, became a desperate reliance on the internet and modest printing efforts, barely sustaining access to knowledge and literary expression.

And when Hamas assumed power, the Gaza Strip became besieged, enduring a series of Israeli assaults and military operations that claimed the lives of thousands of this bereaved population. The infrastructure lay in ruins, leaving Palestinians preoccupied, consumed by the struggle to rebuild amidst destruction, while the occupation methodically devoured the West Bank – Judaizing land, erecting new settlements for a people brought to a land with deep-rooted, native owners since the dawn of history.

In Gaza, Palestinians endure with very little. Internal political divisions have further marginalized the already neglected role of culture, which the Palestinian Authority allocates less than one percent of its budget. Islamic movements in Gaza have displayed indifference in cultural initiatives, even within their own institutions – an approach that, regrettably, mirrors that of official Arab and Palestinian governments.

I remember vividly August 2018, when the occupation destroyed the Said al-Mishal Center. A space that was once a sanctuary for dreamers – young people seeking beauty through painting and poetry, cultural evenings, theater performances, film screenings, and book signings. Its destruction reduced more than just the building to rubble – it crushed the spirit of a community and extinguished the dream of a special cultural haven.

Home to a large theatre and multiple exhibition halls, the Center was where we witnessed countless artistic and theatrical performances by Gaza's celebrated artists, signed our literary works, and collaborated with the Press House, which nurtured young talents. Yet, we found ourselves mourning not only the loss of the Press House but also its founder, the late martyr Bilal Jadallah.

Then the massacre came, extinguishing the very dream of life itself – beyond the dreams of writing or painting. The occupation deliberately targeted human existence, not just Palestinian identities, committing acts of genocide unparalleled in modern history. Even stones and trees were razed, leaving the people of Gaza grappling with a single, desperate concern: preserving their lives and families. But, even this modest aspiration became an impossible dream under the relentless shadow of planes raining barrel bombs on fragile homes in overcrowded refugee camps.

Homes seemed to lean on one another, bleeding and mourning entire lives, dreams, and memories.

Each fragmented ruin tells a story: That crumbled wall once held a photograph of a young man who lost a leg in the war. That patch of paint was chosen after a wife insisted on a shade of gray she admired in an old Egyptian film. Those scribbles on the wall belonged to children dreaming of becoming doctors and engineers. That tattered painting was crafted by a child who had won second place in a school competition on children’s rights. That shattered frame held the bachelor’s degree of a young man who fled south seeking safety, only to be killed by a soldier’s bullet. And those scattered kitchen utensils were purchased after countless arguments between a husband and wife over a paycheck too small to meet the household’s needs.

These images cascade, but for the ordinary, disoriented citizen searching desperately for food to feed their children, such destruction becomes a blur. The loss of the Gaza Municipal Library means little when survival itself hangs in the balance. Food – any food – becomes the sole focus amidst a suffocating siege in northern Gaza, where even animal feed had run out.

I remember, during that grim chapter in human history, how I joined my neighbour – the so-called ‘thief’ – to scavenge through the abandoned homes of those who had fled south in search of safety. We searched for anything – an old can of tuna, a handful of flour, even dog food.

Together, we went to the northern beach area, the ominous buzz of drones and the quadcopters overhead. We recited the shahada, weaving through alleys and the rubble of shattered homes to reach a house we knew. Entering through a gaping hole in the wall, we climbed cautiously to the first floor as artillery fire thundered nearby, targeting other ‘thieves’ scavenging for food for their children. My body trembled with terror, but my friend said: ‘Don’t be afraid; you’ll make it back to your kids. You’re here to feed them, not to steal.’

As a university lecturer and director at a respected institution, I found myself silently pleading with God not to let me die in the home of a family I would never meet. My friend suddenly shouted with joy: ‘Come here!’

I hoisted sacks of bread and flour while he carried a plastic container of clean water – a rare treasure in Gaza, where Israel had bombed desalination plants, leaving the available water unfit even for animals.

We fled as the drones circled above, quickening our steps toward the displacement shelter in Al-Shati Camp. My friend laughed, and said: ‘Don’t worry, they know we’re here to steal, not to resist.’

We returned victorious. I carried 15 kilograms of flour – a triumphant knight with enough to sustain his family for a month. Others died searching for food. My cousin, Ahmed Mohammed Al-Ghoul, was one of them. He vanished, his 31-year old body discovered only after the occupation withdrew months later. By then, it was barely recognizable, riddled with shrapnel and decomposed. Perhaps animals had scavenged his remains, as they had with so many martyrs of this genocide. Or perhaps the bombs had ripped him apart, just as they had ripped apart our homeland.

Looking at the ruins of the city, Yousri al-Ghoul, Gaza City, June 2024

Between my grandmother, who sought refuge at the UNDP headquarters and found no water to drink until my uncle placed a container under the air conditioner’s drainage pipe to collect the trickle, and Gaza Municipal Library, where people stole books to light fires for cooking, the culture of civilization and humanity crumbled. The beleaguered citizen lost faith in both Arabism and Islam amidst deafening popular and official Arab silence and a dubious global complicity.

Books no longer held a place amid the bloodshed. The mask of the silent Arab elite had fallen, leaving behind women who had lost their femininity, burning those letters and words to cook meager meals – the wild herbs we gathered from fields soaked in gunpowder, blood, and remnants of scattered missiles.

Amidst this, I returned home and found my library – whose collection had taken over twenty exhausting years to assemble – reduced to ashes. Despite this devastation, I tried to document the scene, photographing the books crying on the soil of a city drowning in its grief.

As I stood there, a group of children, robbed of their childhood, approached. No longer did they go to school, watch television, or play in parks and playgrounds. Instead, they worked, transporting food, gathering firewood, and queuing for bread. When they saw the scattered books, they exclaimed joyfully, ‘these are perfect for lighting the fire’. They carried the books home with them, triumphant in their defeat.

I, too, left my house, wandering between locations in search of food. On my way, I passed the Rashad Shawa Cultural Center, once the largest and finest venue for grand events in Gaza. I stopped for a picture at its destroyed entrance, surrounded by memories of Diana Sabbagh’ library, the vast halls, and walls that had whispered their connection to letters and ideas.

From there, I continued walking to the bookstore of my friend Samir Mansour, a cornerstone of Gaza’s cultural scene. This bookstore had championed the works of young Gazan authors, bringing their voices to the world through participation in Arab book fairs. But when I arrived, I was confronted with a scene of utter devastation – a vision of hell. The books were reduced to ash, just like those of my friend Atef Al-Durra, the founder of Dar Al Kalima for Publishing. He had fled to the southern part of the Strip, leaving behind a lifetime’s work to burn alongside the homes of his neighbours.

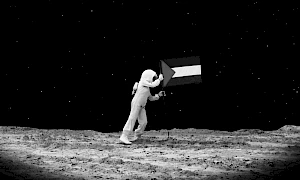

Between the books and libraries, a realization took hold among this Palestinian: liberation is impossible as long as the minds of the young remain occupied. The enemy knows this too, which is why they burn our books, kill the heroes of our stories, and even steal our identity – claiming our heritage as their own. Traditional dishes like shakshuka, falafel, and hummus are presented as Israeli, part of an erasure of our cultural essence. Yet they fail to grasp that the Palestinian spirit is indomitable. As long as our language survives, we endure.

Gaza’s writers have turned to their words during this massacre. Through diaries and texts published in newspapers, magazines, and books, they recount the suffering. The Ministry of Culture’s recent publication, Writing Behind the Lines, documents the massacres committed by the occupation, as does the book The Commandments, which I had the honor of supervising.

The targeting of Gaza’s historical sites only deepens the pain. The enemy’s attacks go beyond the present, striking at our very roots: the Great Omari Mosque, Qasr al-Basha, Sayed al-Hashim Mosque (named after Prophet Muhammad’s grandfather, peace be upon him), the Byzantine Church, the historic Al-Ghussein House, Al-Saqqa House, and countless other irreplaceable landmarks, that cannot be confined to a single testimony. It is as if they are declaring: ‘We will crush you at your roots.’ Yet they underestimate the Spartan-like resilience of the Palestinian people – unyielding and enduring, as Hemingway wrote in The Old Man and the Sea: ‘A man can be destroyed but not defeated.’

So how can the Palestinian, the rightful owner of this land, ever be defeated, especially now, as the world begins to awaken to the savage brutality of the colonial Zionist occupation?

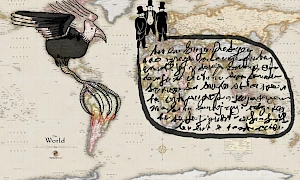

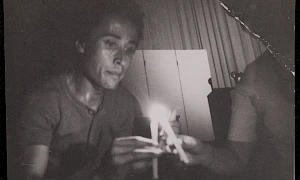

Collecting wood for fire, Yousri al-Ghoul, Gaza City, Spring 2024

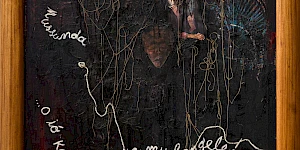

Not long ago, I visited Shababeek for Contemporary Art, where I often sat with friends Majed Shala, Shareef Sarhan, and Basel Elmaqosui, the founders of this important artistic space. Upon arrival, I found the paintings I had once hoped to adorn my new home with completely ruined – torn and saturated with rainwater – after the occupation wiped the area off the map during the incursion near Al-Shifa Hospital. Yet, the inspiring part of this story is that Basel, Majed, and Sherif refuse to stop painting, even in their places of displacement. More than that, they are teaching children to paint, just as I once did with boys and girls at the Asma School run by UNRWA, which had become a shelter after the school year ended without education and over 15,000 students were martyred.

I still remember Sumayya Ghazi Haniyeh, 16 years old – may she rest in peace – who used to come to school asking for recommendations from the library that still functioned at the shelter. She would listen eagerly as I spoke about literature and writers, soaking in every word. But Sumayya’s fate mirrored that of thousands of girls in Gaza. She was killed when an F-35 strike obliterated her family’s home. Even as I write this testimony, her body remains buried under the rubble. Sometimes I find myself visiting the site, as if to tell her more stories, longing to hear her ask me once again, ‘Why didn’t I become a superhero like the characters in your stories, Yousri?’.

In the camp, where rubble and sewage water chokes the streets, where the stench of decomposing bodies clings to the air, it’s nearly impossible to pass a child who doesn’t engage you in profound conversations about survival – discussing how to cook without wood or gas, when the city has run dry of both.

They speak with a startling practicality, paying little mind to the blood in the streets, the trash piled high, or the omnipresent hum of planes that has become a permanent fixture in our memories.

And then, they suddenly ask, ‘When do you think the war will end?’.

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

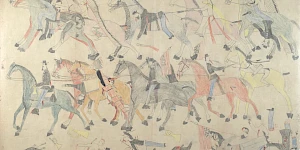

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials