Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Published to accompany ‘The Lives of Animals’, first presented at M HKA (Antwerp) in 2024 and now on view at Salt (Istanbul) – philosopher Fahim Amir explores the shifting dynamics of human-animal relationships in face of global health crises. From the workers' struggle for coexistence with persecuted animals during early 20th-century epidemics in Rio de Janeiro to the recent Covid-10 pandemic, Amir reminds us that ‘there are not only viral leaps between species, but infectious solidarity as well’.

Dedicated to the memory of Marion von Osten

2020 is the year when a microscopic entity left its mark on the young third millennium. All eyes quickly turned to medical laboratories as heroic figures in the salvation story of this pandemic. In the Sick 80s,1 the laboratory had been a site of biopolitical militancy: AIDS activists staged ‘die-ins’ to shed political light on the lack of medical research into the ‘gay plague’. At the same time, animal-rights activists liberated the collateral victims of medical progress and initiated public debates about its legitimacy. Subsequently, the laboratory became a space that hermetically sealed itself off from the clandestine intrusion of outsiders and the uncurated distribution of potentially incriminating documents. A public debate on the actual nature of medical research like the one in the Sick 80s would appear to be crucial, but at the moment nothing seems more remote.

With the COVID-19 pathogen, old-fashioned parochial nationalism made a comeback. While the public discussion demanded fact-based policies, the focus shifted away from the causes to the effects. Thus, the question of whether the pandemic was a symptom of late-capitalist animal exploitation disappeared from public awareness as quickly as it had appeared. More precisely, to paraphrase the French philosopher Jacques Derrida: not in spite of but because of the fact that the animal question arises everywhere, it cannot really be broached anywhere.2

Thinkers of all stripes seemed to promptly reject any idea of nature or animals taking revenge, either invoking instead the immanence of capital or seeking their salvation in dusty, old-school humanism. But even among humans, ‘revenge’ is not always a perfidious plan of malevolent minds. Often – like the Afghan badal or the Italian vendetta – it is a social practice that leaves little room for individual decisions or sentiments. Then again, in present-day capitalism, nature is at the center of production and reproduction. This makes it a site of crisis and revolt. But those who can think the political only in terms of civil law and order miss what makes this site political. The free and sovereign will legitimizes the signing of an employment contract, a confession, or a petition. In short: modern subjects go to the workplace, to prison, and into the voting booth. This problematic normative constriction rejects everyone and everything, humans and nonhumans alike, whose bodies or minds do not speak the language of sovereignty.

Animals, however, not only escape from liberal enclosures, but they also overburden textbook Marxism. Instead of grasping the tragedy of the current situation as a compelling reason to reevaluate traditional categories and cognitive patterns, one of the most baffling aspects of the pandemic is the glaring poverty of ideas surrounding it. The world seems to be on the verge of collapse, but looking beyond the white male heterosexual industrial worker as the primary subject of history still appears to many otherwise critical minds as ‘a touch too much’.

As we know, the burden of the pandemic is unjustly distributed. Women and migrants constitute the majority in most of the so-called systemically relevant occupations, from retail to health care to home care. The burden of our health, however, is also borne by countless (often female) nonhumans, as the installation Novogen (2017–18) by the Hungarian artist Dániel Szalai makes us aware. It consists of 168 individual portraits of laying hens of the eponymous commercial breeding line. These are clones, meaning they have an identical genetic construction kit. But in Szalai’s photographs, they recall historical portraits of individual workers. Their bodies are factories for our health, because their eggs produce the flu vaccines that are administered annually to worried Europeans at the beginning of the winter season. Thus the hens are workers and factories at the same time, individuals and clones, long-since dead in Hungary, but parts of their bodies circulate long afterward in countless European veins.

Meanwhile, a race has begun to see which country will be the first post-pandemic ‘vaccination’. The words ‘vaccine’ and ‘vaccination’ are derived from the Latin word for cow, vacca, since administering cowpox (and horsepox) was the first successful form of immunization against smallpox. Chains of transmission are not one-way roads either; historically, it is likely that far more animals have been infected by human pathogens than the other way around.

The stressed bodies of bats played an important role in the genesis of the current pandemic. Locally, norms and taboos had long restricted the killing of bats. But since dead and living bat bodies have become profitable, a contest for their bodies has broken out. At the same time, mining, plantation farming, and lumber depletion have destroyed their habitats at grueling speed. Stressed to death, their immune systems go haywire, turning them into chronically feverish bioreactors. Hounded to death, they swarm in search of asylum and end up near animals that are equally weakened by hunting or husbandry: ideal conditions for chains of viral transmission. In eastern Australia, for instance, bats learned to live in trees near horse pastures (leading to Hendra virus). In Malaysia they turned up in the vicinity of an up-and-coming hog industry (Nipah virus). In Saudi Arabia, where animal farming had changed over from nomadic to sedentary, they took up residence in camel stalls (MERS).

When the first minks on Danish fur farms became infected with COVID-19, they were killed and buried without delay. The gases produced by decomposition, however, pushed the dead mink bodies back to the Earth’s surface. A subsequent news headline read: ‘Culled mink rise from the dead to Denmark’s horror.’3 Something, however, is not only rotten in the state of Denmark, but anywhere people think that simply burying and carrying on is the best way to proceed in a catastrophe. Every kind of cultivation and hunting of animals for which ‘intensive’ is a euphemism is the real horror. As long as this does not change, the current pandemic is only an appetizer for the courses that the coming century will serve up to us.

The connections, similarities, and relationships between our bodies and those of animals are the hinges that open the door to the viral will to reproduce – accelerated by the infrastructures of the world economy and amplified by social inequalities like those in nutrition, healthcare, and housing. Whether it was – as first surmised – pangolins pushed to the edge of extinction that served as the wet bridge for the virus between bat bodies and our own, or whether – vice versa – the virus first circulated in pangolins before jumping across to bats and then to us, or whether some other animal was involved, has not yet been determined. But we do know that we have hunted down these and countless other animals in the most remote corners of the world and swallowed up their habitats. With COVID-19, our social spaces became smaller and smaller as well. First, we locked up the animals in factories, and now we are trapped in our own apartments and workplaces. You could call this an especially strong form of feedback, or revenge.

Elucidating our relationships with animals, tracing their complexities, and learning to understand their consequences has been turned by the pandemic into a historic task. This may also mean that we need to develop a new register of notions, a counter-vocabulary to the semantics that constantly cause us to lose our ideational grip. An intellectual tradition that absolutizes the otherness of nonhumans because it has fallen in love with its mirror image will presumably fail at this task. Thus, in one of the most quoted essays of the twentieth century, the philosopher Thomas Nagel poses the question ‘What is it like to be a bat?’ – only to promptly set it aside as unanswerable.4 The deficient objectivity here consists in the trick of a perspective from nowhere that conceals its own situatedness instead of making it part of the reflection. Imagining what it is like to be an older white professor at an elite US university would probably be just as difficult for the majority of humanity.

Brazil: 2020, 1903, 1937

Pandemics do not only have dystopian dimensions, with animal bodies at their beginnings and ends. As natural born punks, animals can harbor utopian hopes even in dark times. Thus, in the first summer of the COVID-19 pandemic, a large, flightless bird called the rhea became the hero of the progressive forces in Brazil. Communist Congresswoman Jandira Feghali professed to be ‘100% Rhea’.5 Margarida Salomão, a university professor and a leading politician in the Workers’ Party, declared on Twitter: ‘This rhea represents us.’6 But how did this becoming-bird of the higher-ups in the Brazilian workers’ movement come about? In the spring, a rebellious rhea had already been attracting attention.7 At a press conference, the notorious coronavirus skeptic President Jair Bolsonaro had offered one of these creatures a package of the medicine chloroquine (hardly effective against COVID-19). The rebellious rhea, however, wanted none of it and promptly turned tail and ran. Images of this presidential failure amused many people who didn’t think much of Bolsonaro’s ostrich-like policies. Three months later, he himself became infected with COVID-19 and was forced to withdraw into self-isolation in the presidential palace. When he tried to feed one of the rheas that live there, the recalcitrant fowl bit back at him in a flash. The ex-general, otherwise so commanding, retracted his hand in fear, but someone had already managed to photograph the embarrassing episode. Now, a huge wave of ridicule washed over the politician. It may be that a whole country had succumbed to his seductive wiles, but that bird did not. ‘Rhea-sistence’ gained national significance as an entertaining media phenomenon, but the spontaneous identification with the bird can also be interpreted as comic relief in desperate times. It is probable that the amusement was also mixed with a sigh of relief that somebody, anybody, had presumed to be so insubordinate, even if it was an odd bird.

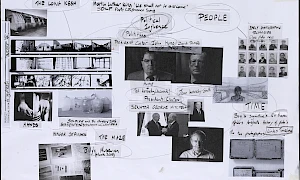

Of a different nature was the solidarization a century earlier of numerous Brazilian workers with persecuted animals, as described by the anthropologist Nádia Farage.8 At the beginning of the 20th century, Rio de Janeiro, as an important commercial port, had been forced to lament a series of recurring plagues (yellow fever, smallpox, bubonic plague) that endangered the exporting of coffee and frightened off investors. Blame was placed on the narrow lanes of the old town and on the labyrinthine slums that the intellectual elites considered a symbol of the country’s backwardness. The modernization of the city center and the harbor district, begun in 1903, was guided by sanitary measures that included not only demolishing the old town, but also fumigating the slums, and often incinerating the residents’ possessions. The rights of those affected mattered little, which is why critics called the measures “sanitary despotism.” A campaign to exterminate harmful creatures (flies, mosquitoes, mice, rats) was launched, and the expulsion of agricultural animals (cows, goats, donkeys) from public spaces was undertaken. While delivering captured strays to medical laboratories had once been considered, all stray dogs were instead captured and killed, as were all dogs whose owners hadn’t applied for a license or couldn’t afford the required fees. Thus, in 1903 and 1904 alone, the cadavers of 13,000 canine enemies of the state piled up.

During Carnival, many residents of Rio displayed sympathy for animals by dressing up as them, thus filling the city with precisely those creatures that had been banned from staying there. This included a parade in defense of dogs that made fun of the division into licensed and unlicensed dogs. Many poor people recognized themselves in the persecuted animals, for the city government was likewise trying to make it impossible for the unemployed or the unofficially employed (sex workers, beggars, vagabonds, street vendors, slum residents) to inhabit public spaces. But this was not limited to mere symbolic solidarity. Newspaper articles from this period report that groups of workers were waylaying dog catchers and freeing the captured dogs, making it necessary to dispatch armed units to protect the catchers. A strike by coachmen and haulers in 1904 began with an attack on a dog catchers’ wagon, which was broken open to liberate the captive animals. Apparently this met with the approval of the local population, since it turned out to be only the first liberation. Farage argues that ‘if bio-power symbolically equated animals with poor men, the workers’ reaction was not to negate the equation, but to creatively turn it into a struggle for life’.9

Such trans-species solidarity did not arise in a vacuum. In Rio’s workers’ associations and periodicals at the time, many ideas circulated that were influenced by Leo Tolstoy and Peter Kropotkin. The latter, in his book Mutual Aid (1902), had discovered an intensive sociality between species,10 which many transferred to their own urban situation.

Sanitary despotism won the day, but solidarity between species remained in the public memory well into the years of the Vargas dictatorship. The samba ‘Cachorro Vira-Lata’ (‘Mongrel Mutt’), composed by Alberto Ribeira in 1937 and sung by Carmen Miranda, goes like this: ‘I love a stray dog that runs alone through the world, without a collar and without a master.’ The samba goes on to point out the burden of class on animals as well – while some enjoy lunch and dinner, others don’t even have a bone to gnaw on. But along with stressing the shared class conditions, a human voice conveys sympathetic fondness for a stray dog. And the stray dog in the song, without a collar or a master, pays homage to the anarchist slogan ‘No gods, no masters’.

In the same year that Carmen Miranda sang the praise of the stray dogs of Rio de Janeiro, the attorney Heráclito Sobral Pinto, also in Rio, assumed the unorthodox legal defense of Harry Berger, a member of a Communist cadre from Germany who had been subjected to torture, social isolation, and food deprivation for two years in a special police cell. As a political prisoner during Getúlio Vargas’s recently declared state of emergency, Berger enjoyed no normal civil rights, and so his lawyer attempted a defense strategy that seems daring today. He defended Berger insofar as he was an animal. That is, the government had recently defined animals as legal persons, thus placing them under the protection of the Brazilian national state. If Berger had no claim to protection as a person (because he was a Communist, a Jew, and an alien), he did have such a claim inasmuch as he was also an animal. Pinto asserted that the same rules that apply to farms and slaughterhouses, where the government had mitigated inordinate cruelty, must also apply to prisons. Because of his defence of rebellious Communists, Pinto is considered in Brazil to be the father of human rights (which would not be declared by the United Nations until 1948). For the Argentine thinker Gabriel Giorgi, Berger’s body signifies an unrecognizable, legally unreadable, ontologically indeterminate figure between revolution and fascism.11

Both the defense of animals by the slum dwellers of Rio and the defense of Berger by Pinto would soon no longer be politically intelligible. At the beginning of the twentieth century, both sides of the Atlantic were characterized by a zeitgeist that felt close to manifestations of life, the natural word, and the findings of biology. This ‘naturalism’ comprised a broad palette of cultural and political trends extending from social Darwinism and nationalist ideology to Art Nouveau, the London Bauhaus, vitalist philosophy, youth movements, and nudism. This conceptual space, which also implied an openness to connections between the fates of animals and the fates of humans, came to an end after the atrocities of National Socialism and the fascist equation of humans and animals. The unification of humanity was purchased at the cost of the segregation of animals. In 1947, the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights focused on the commonalities among humans. In 1950, a UNESCO commission of anthropologists and sociologists turned this contraction of humanity into science by eliminating the cultural and social significance of biological subdivisions of the human species such as ‘race’.12 Both the United Nations declaration and the UNESCO report are expressions and forerunners of an epistemic break that would henceforth make it difficult, if not impossible, for even progressive forces to imagine any political continuity in the relationships between species. The horizon of the political imagination had shrunk to include only humanity.

Yet, in the past few decades, scientific insights have eroded the borders between species. Ecology, women’s, queer, and animal-rights movements have contributed to a new atmosphere – especially among the very young. Against this background, new constellations have appeared on the scene that pick up the thread politically where it had been epistemically torn off.

The World Spirit Is a Dog in Chile

During the student protests in Chile in 2011 and 2012, a quiltro, a stray dog, drew attention to itself. He took part in demonstrations and plenary assemblies, and in clashes with law enforcement he could always be found on the side of the students. The dog with black fur and a red bandana became known as Negro Matapacos (Spanish for ‘Black Cop-Killer’). Even long after his death in 2017, images of this canine icon of resistance graced many walls in the public spaces of Santiago de Chile.

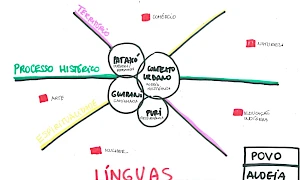

In 2019, a new wave of protests broke out, but this time they were borne by large segments of the population. To be sure, the coronavirus forced an inter- mission, but the protests gathered speed once again in the fall and peaked in the historic vote on constitutional reform. This movement – with its historical milestones, like a feminist demonstration with three million participants (out of a population of eighteen million), or the historic solidarization of parts of the slum population with the LGBQTI movement – shook the country’s political system. That system is based on the expropriation of the indigenous Mapuche, the disenfranchisement of the “mixed-race” population of mestizos, and a constitution that guarantees political power for the biggest taxpayers. After the socialist dream of Salvador Allende ended, the Pinochet dictatorship set about enforcing the market extremism of the Chicago Boys in all areas of life. But now the problems of more than forty years of constitutionally grounded neoliberalism have exploded at the same time that the 400-year-old conflicts with the Mapuche and mestizos have flared up in their wake – augmented by new political dimensions such as the freedom of desire, ecological concerns, and increased sensitivity to animal politics. The movement is consistent in demanding not only the reconstitution of Chile as a multinational and multiethnic state that guarantees the rights of Indigenous peoples, but also gender parity in parliament and constitutional status for queer rights.

While the movement seems to get by without leaders, spokespersons, or speechwriters, three representations dominate: flags of the Indigenous Mapuche; black variations of the national flag referring to anarchist traditions and signifying the absence of domination; and on thousands of buttons, T-shirts, and banners – Negro Matapacos. He is not only part of the movement’s history of resistance, but he also represents a narrative ‘from below’. After all, it is hardly possible to sink any farther down ‘below’ than a quiltro. But what is a quiltro?

In the film Kiltr@ (2012) by Lissette Olivares and Cheto Castellano,13 the poet and thinker Carmen Berenguer points out that the word is not included in the Royal Spanish Academy’s dictionary:

It is a word from Mapuche or Pehuche. When the Spaniards, the colonizers, arrived, these dogs were already in Chile. They were very small dogs, and many of them formed packs. These small dogs even put pumas to rout. It is said that the quiltro is a dog of mixed (mestizo) breed. We devalue dogs by calling them quiltros because this means they are not purebred. That is why the term quiltro is also used to denigrate people who live on the streets.

As a masterless stray, the quiltro embodies an antithesis to the domesticated, brutally trained purebred dogs of the Chilean military and police. In contrast to the obstinate Brazilian rhea or the Greek riot dog Loukanikos, however, Negro Matapacos is more than a progressive symbol or media event. Negro Matapacos fulfills a historical role. He is the face of a faceless movement of the many. He is full of identity, but at the same time beyond neoliberal identity politics. He communicates and propagates a collective political affect. As a mongrel, as a street mutt without noble pedigree, he is a permanent alien with no right of residence in the heroic, patriotic history of Chilean nation building that has been recited since the end of the colonial period. He does not stand for any specific content, but for subalternity and insubordination themselves. Negro Matapacos represents a sort of extraterritorial place. Therefore, he does not lend himself to representing any particular interest. He who was not represented anywhere has now become the representative of all. The metaphysics of revolt has a new entry, for in many popular depictions, the quiltro is titled the ‘patron saint of demonstrations and stray dogs’. Like a virus, the new saint of dissent and revolution propagates itself laterally, because many solidaristic people also adorned their household pets with red bandanas. In short: Negro Matapacos is a political super-spreader of revolt and solidarity.

When in Chile, as elsewhere, the statues of great men and colonial masters fell, in some locations statues of Negro Matapacos replaced them (and some of these were then removed and dragged through the city by fascist forces). Paul B. Preciado points out that conventional statues are sculptural manifestations of biopolitics, petrified ghosts of the past, which as ‘prostheses of historical memory’ give form to some bodies and not to others, thereby helping to constitute a pure national body.14 Negro Matapacos is in this sense a political anti-body. He does not represent any normative political body, but profoundly calls that body into question. Incidentally, the riot dog did not remain alone. In other cities in Chile as well, quiltros have joined the movement.

Their participation in protests not only casts the seeming naturalness of their social status into doubt, but also causes the borders of the political to collapse in a way that touches utopian shores. “A revolution,” as Preciado remarks, ‘is not just a supplanting of modes of government but also a collapse of modes of representation, a jolt to the semiotic universe, a reordering of bodies and voices’.15 This makes these dogs revolutionary subjects par excellence.

In 2020, we learned that health care must be public, because health is public as well. And we learned that solidarity with animals promotes public health. The dead in this story also warn us, in the midst of the efforts to combat the pandemic, not to forget that hygienic ideas for combatting dangerous fevers derive from colonial medicine. The motivation for colonial medicine was always geopolitical, and it usually directly served to support colonialist incursions and enterprises. Tropical medicine and troop medicine are not only semantic twins.16 As artist Natascha Sadr Haghighian points out eloquently: ‘Even though we like to invoke the integrity of the individual or of life or of the nation, the history of epidemic control reminds us that it is never a question of protecting all bodies.’17 Whether through reckless disregard or methodical organization, there is always an excess of death. The sciences are often accomplices of power. As the geographer Kathryn Yusoff has shown, we actually have to speak of ‘white geology’, because historically, this science established itself with an eye toward the discovery, exploitation, and extraction of mineral resources.18 To be able to understand our times and act appropriately, we need a more complete view of the world and the forces acting within it. Decolonizing the sciences and dethroning the human being as the sole subject of history are therefore not only desirable but also urgently needed politically. The pandemic is no time for intellectual faintheartedness. True, there is no reason for optimism, but things are also not hopeless, thanks to subjects of history who prove that there are not only viral leaps between species, but infectious solidarity as well.19

Related activities

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

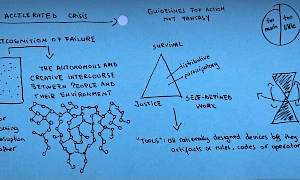

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

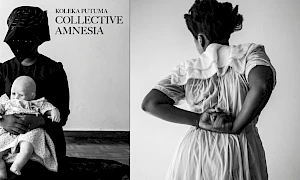

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations