We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

This conversation is an edited version of a panel of the same name, which was part of ‘Climate Forum III – Towards Change Practices: Poetics and Operations’. ‘We, the Heartbroken’, which takes its name from sociologist Gargi Bhattacharyya’s 2022 book, extends a series of workshops by artist G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide in conjunction with the Van Abbemuseum’s collection department, exploring how death figures within heritage institutions. At stake is the possibility to consider the life and death cycle of artworks, breaking the stranglehold of infinite accumulation and conservation that is at odds with acknowledging climate breakdown, practices of sustainability and care.

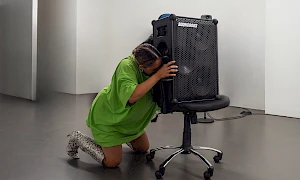

G, WHAT WOULD IT BE IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D, 2021, installation at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, OPEN 2021, featuring five clay sculptures, Morse-code programmed lighting and wall drawing. Photo: Sander van Wettum. Courtesy the artist

G: This is a body of work which I finished making in 2021. I think time has gone weird on me – us all – these past few years. There were five works and they all took about nine months to make, which also reminded me of a life cycle. The Morse code lighting omits a message that appears every five minutes and says ‘Go away’, ‘Leave me alone’ or ‘F off’, depending on who you ask. I also had the floor-to-ceiling drawing of ‘2020’ on the back of the wall, which remains unfinished, and always will, because there’s still work to do and questions to be answered from events that happened in 2020: political uprisings, Black Lives Matter, the #MeToo movement, Covid-19. I was also interested, and always will be, in the ephemeral – those moments on the bus or when you come out of the shower and condensation reveals a past drawing or an imprint of a resting head. Often simple, quick sketches – hearts, Superman ‘S’s, a crush’s name, phallic shapes.

In the deep throes of grief, I would follow lookalikes of my father, or things I believe were sending me a message, or animals I thought he had become reincarnated as, or children who looked like my siblings holding his hand or playing. So, since his passing, which was eleven years ago now, I have been making work about grief and life. I only recently realized that I had started doing it before he passed. It’s something I think you always work through in some shape or form. With this body of work, I’d ask myself: ‘WHAT IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D?’ ‘How could I give shape to something or someone that’s no longer physically there?’ The works were all kind of intuitive, there were sometimes quick rough sketches in order not to give Marianne a migraine (shout out to Marianne Peijnenburg, ceramics specialist without whom none of this would have been possible). I often had a clear idea of scale but I allowed this to shift depending on how things felt, which in the end came with a lot of challenges, like how to move these massive things. I had no idea how much they weighed, I wasn’t really thinking about practicalities. ‘About the weight of a baby elephant’, I often say as a semi-joke when asked.

G, WHAT WOULD IT BE IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D, 2021, installation at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, OPEN 2021. Photo: Sander van Wettum. Courtesy the artist

There are three sorts of ‘prongs’ in the series: myself, my mother and my father. There are also references to Christianity present in some of the works, as I grew up in a religious-ish household. But I wasn’t holding any of this, really, in my mind. I was just moving through it.

All the everyday objects in the space – the carpet, the washing machine, the stretcher, the leather boots – were items that were either discarded, thrown away, or chosen to be given away: the second-hand leather boot from a once-alive cow; the frame from discarded wood; the sheep’s wool from a ‘free bin’ of offcuts in a textile store; the engraved conch shell that was once the shelter of a living being, from my mother’s land, Barbados.

G, WHAT WOULD IT BE IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D, 2021, installation at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, OPEN 2021. Photo: Sander van Wettum. Courtesy the artist

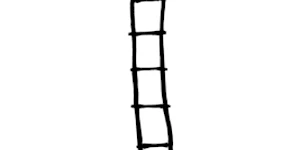

One thing that was bought, though, was the bows. After years of trying to feel through life after loss and death, in this work I wanted to kind of honour/celebrate life; so every year it would have a birthday. Each year I celebrate by adding a bow, as a way of remembrance; instead of flowers, I decorate it/them with a symbol to show the time; something like a present. The symbolism of the washing machine speaks about how grief can come up on you in moments when you least expect it, like flashbacks or sound glitches, or the scent of a passing person, even in an action completely seemingly unrelated to a memory of someone.

Time goes back and forth, and you can’t wash grief out; it doesn’t work like that. It just shifts and morphs and changes. So the washing machine is an important part of the work.

G, WHAT WOULD IT BE IF THE THINGS YOU CANNOT SEE AND ONLY FEEL WOULD BE IN 3D, 2022. Bow evolution: satin bows dipped in glass resin for every yearly celebration. Photo: G (? To check). Courtesy the artist.

These sculptures will continue to be made throughout my life cycle. I am curious to see how my body changes throughout the different phases of life and age and how I approach, tend to or confront the material. I’m currently making one involving satellite dishes coming together, as a way to communicate with people that are no longer here. Dish-to-dish wouldn’t work, so I guess it could be seen as saying you cannot speak to ones no longer here. But I don’t necessarily think that’s true, it’s just the feedback – the response – won’t be what you’re used to.

Work in progress, made by G at EKWC residency, the Netherlands, with the support of Stichting Stokroos, 2025. Photo: G. Courtesy the artist.

I also made a performance. I perform a lot, especially for the camera, it has become my way to communicate – actually doing interviews and presentations like this makes me nervous, as it can feel so static. I performed with my dad’s ashes and turned an urn into a handbag so I could rave with him. The score of music at the beginning was the opening of the performance. Produced by Cheb Runner, it’s called MISSED CALL (2002). I dance and interact with the sculptures through the performance. It’s fifteen minutes long. The score becomes a really fast jungle drum-and-bass track, alongside my dad’s voice, snippets of my granny singing, and heartbeat sounds. It takes you along the route of my life so far. Jungle was the music of my youth, and even now I believe that raving, dancing, makes me stronger and somehow also trains me to be emotionally stronger. It brings me back to my body and out of my head, which is important for me.

G, MISSED CALL, 2022, durational performance with handmade urn handbag of the artist’s father’s ashes, commissioned by Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven; sound piece produced by Cheb Runner. Photo: Özgür Atlagan. Courtesy the artist

G, THERE ARE (MANY) PARTS TO THIS – 3, 2025; MISSED CALL XL, performance, 20 min, borrowed car, soundtrack produced by Cheb Runner with audience members. Photo: Sophia Xu. Courtesy Marwan Gallery and Van Abbemuseum

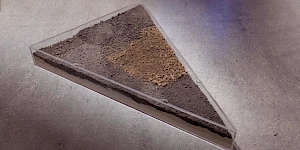

This is another piece of work: THERE ARE (MANY) PARTS TO THIS – 1 (2024). I used Albert Heijn supermarket shopping-bag handles, and all of the objects are cast metal. When I was thinking about if I were to make my own urn, which I have, what objects would symbolize the kind of life that I live, or that I’m hoping to or trying to live? I never turned them over to be revealed because I don’t think that is the point. You have various things here: the sheet I’d had for the last decade; a mouth guard; and other things which will remain hidden, because I think it’s fun to imagine and it’s more about us all than what my objects are. But the shopping-bag handles were fixed upwards, as if to say that you can’t really carry all your own shit. You need people in order to live through life, so it’s impossible to lift it alone without destroying it.

G, THERE ARE (MANY) PARTS TO THIS – 1, 2024, casting sand, found objects collected over the past ten years, hand-poured aluminium. Photo: Franzi Müller Schmidt. Courtesy the artist and Marwan Gallery

One small detail is these kind of Barbie figurines. The square is also a laptop. I was interested in social media trends. I would see a lot of adults starting to play with kids toys, making tiny cups of tea and things like this. I read it as a self-soothing activity and I thought it was interesting it happened in adulthood, people soothing themselves in this way.

G, ENGERLAND PART 2, 2021, 4 min 13 sec, filmed by Artor Jesus Inkerö. Courtesy the artist

ENGERLAND (Year 2017–) is an ongoing series of films which I do every four to five years when there’s an election in the UK. I will do this until the end of my life. So, the next one will be in 2025 or 2026.

G, YOU ASKED FOR IT YOU GOT IT, 2020, performance still, performance with artist’s mother at Emalin Gallery, London. Photo: Katarzyna Perlak. Courtesy the artist

I perform a lot with my mother; she has taught me a lot about performing. We dressed nearly identically in this work apart from she had a smiley face drawn her shirt and I had a sad face on mine. In this still, we’re embracing; there was a live percussionist, a family friend (Skins), and my mother and I were performing the dance routines. Skins has since passed so this piece is now dedicated to him. My mother and I been working together for more than a decade, from before my dad passed away. It’s a way for me to stay with the people I love the most. She’s a big influence on my practice.

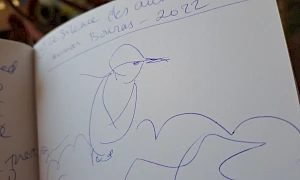

G, GRIEF-SAD-FEELING-WEIRD-OUT-OF-THIS-WORLD Colouring Book, Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, 2022. Cover by Bart de Baets. Courtesy Van Abbemuseum and the artist

As I mentioned earlier, I often find language difficult, especially when thinking through or facing grief. So I made this colouring book, commissioned by the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven). GRIEF-SAD-FEELING-WEIRD-OUT-OF-THIS-WORLD-COLOURING-BOOK (2022). And above, it says: ‘These images were birthed in the quicksand. When it’s unbearable, ask yourself the following questions… What are my favourite things? How do we love ourselves and our shadows? And where are my pens?’. So I hope to bring in elements of humour and drama in my practice. There is grief, but there is also life. I think there’s about nine pages of drawings which people are invited to move through, and in their own time.

That is me.

Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide: Picking up from where G left off, G and I are thinking about the question of death/life cycles in the context of the museum. G and I have been in conversation since 2022 about how death and grieving can figure in an institution, and I would say specifically a heritage institution, especially if – as G advocates – we are to domesticate grieving and death and integrate them into daily practice. Bringing up this question in the context of a museum means many things. But first it’s important to remind ourselves of the context of the museum, and here specifically that of the Van Abbemuseum.

Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven

Van Abbemusuem, Eindhoven. Photo Peter de Koning & Twyce

Here’s an image of the original building, the first structure of the museum, from 1936 when it opened. Designed by architect A.J. Kropholler, the building is notable for its neo-Romanesque style, reminiscent of Roman Catholic churches. Kropholler was commissioned by the museum’s namesake, cigar manufacturer and founder H.J. Van Abbe. Van Abbe’s cigar company, H.J. Karel I, sourced tobacco from Sumatra and Java in Indonesia, a former Dutch colony. While the Van Abbemuseum doesn’t explicitly display colonial loot, its history, like many others in the Western world, has a colonial foundation. Van Abbe donated a small of 26 collection of paintings to the municipality, along with the building that became the museum. In 2026, the museum will celebrate its ninetieth anniversary, and the collection display that G and I are working towards will open. The museum was founded with the capital raised by Henri Van Abbe, often referred to as an entrepreneur today. Van Abbe’s cigar factory, Karel I, was funded by the tobacco he bought in Amsterdam and plantations owned in the then Dutch Indies. The museum’s origin story is heavily influenced by the slave labour used in plantations in Sumatra, where Van Abbe sourced his tobacco.

The Van Abbemuseum is located in Eindhoven, the main city in the north of Brabant, in the southern part of the Netherlands. Known as the Netherlands’ technological city or design hub, with a population of around 250,000 people, Eindhoven comprises a unique blend of technocratic and agricultural areas. It’s the birthplace of Philips Electronics, whose founder, another ‘entrepreneur’ in our origin story, played a significant, paternalistic role in the city’s development, contributing to urban planning. ASML, the tech company responsible for manufacturing chip-making equipment, has its headquarters in Feldhoven, not far from Eindhoven.1

‘Museum Index’, designed by Laura Papa for Van Abbemuseum, in Charles Esche and Chương-Đài Võ (ed.), The Museum Is Multiple, Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, 2024, pp. 18–19

It’s important to remember the specificities of a museum when discussing its composition. (If we’re not in the same geography, I invite you to think about that of your local modern art museum.) Statistically, our collection looks something like the ‘museum index’ or data visualization above, put together by Joost Grootens and Julie da Silva Lenoir in The Museum Is Multiple, coedited by Charles Esche and Chương-Đài Võ and designed by Laura Papa,2 which reveals some discrepancies: for instance, that there are works by approximately 634 male-identifying artists compared to 143 female-identifying artists (as well as about 58 artist collectives) in our collection of around 3,600 works.

‘Museum Index’, designed by Joost Grootens and Julie da Silva Lenoir for Van Abbemuseum, in Charles Esche and Chương-Đài Võ (ed.), The Museum Is Multiple, pp. 24–25

This representation shows the geographical origin of artists in the collection, based on their birthplace. It’s unsurprisingly European and American–heavy, with fewer artists from Indonesia and South Africa, where I’m from. This is particularly jarring when considering the colonial relations between these geographies. By keeping this data in view, we recast heritage sites as contested spaces – a view which, when discussing resistance, particularly against the frameworks that define museums and artworks and the role of death and life cycles, comprises the crucial contextual backdrop of our position.

G mimicking Francis Bacon’s Fragment of a Crucifixion (1950) as part of the workshop dress rehearsal, Van Abbemuseum, 18 November 2024. To the left, Bacon’s Fragment of a Crucifixion and Guercino’s Andromeda (1660) to the right. Photo: Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

In 2022, G and I began contemplating the life and death cycles of artworks after G’s body-sized ceramic family of sculptures UNSEEN/JUST FELT SOULS, HARDLY LIVING SKIN/ HOME & HEADS (2020–22), and MISSED CALL, a performance tied to her life cycle, entered the collection. Since then, the curatorial and collection team have started considering a death/life cycle for artworks in our collection. This approach aims to integrate questions of death, transition and afterlife, against the usual practice of suspending artworks in time to be conserved indefinitely.

Practically this has involved a re-evaluation of how we, as museum workers and custodians of artworks, can update collection maintenance practices. We’re collaborating with the collections team to develop conservation protocols on a number of case studies – works at different stages of dying. G is also commissioned to design birthday parties and funerals for artworks as part of the upcoming collection display presentation with the working title ‘That Time When We Were Not There’; both forms of commemoration will inform the design and logic of this exhibition.

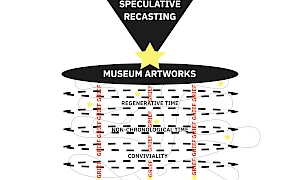

In it, the collection display is further organized around three other research threads exploring time besides ‘Regenerative Time with G’: ‘The Unchronological’ thread, led by Lineo Segeote and David Andrew of the Johannesburg working group of Another Roadmap Africa Cluster, presents a special edition of their unchronological timeline tool, a tool which connects seemingly remote geographies, prompting questions and weaving-in personal stories; ‘Public Time’, developed with Ima-Abasi Okon, draws inspiration from her road-running practice and incorporates art outside the museum’s operating hours; ‘Cosmic Times’, created with Nolan Oswald Dennis, explores planetary temporalities, using the universe to address local concerns.

G has invited us, as well as others working in similar institutions, to rethink and reset our relationship with collections and collecting, while G’s practice has helped us broaden our understanding of death and dying. With the collection team, we’ve begun to define dying as ‘the phasing out of public life due to fragility of artworks’: when an artwork is too delicate to be displayed, we could consider this a form of dying. Similarly, while a work’s deaccession is often equated with its death as it moves out of the collection, G’s practice is helping us to broaden this into a definition: now, if artworks were to enter the private domain (a rare occurrence), we could view this, too, as a form of dying.

Something else I would like to discuss is the concept of recasting and/or speculative narration. I continue to be in contentious relationship with the museum, particularly its collection, because it feels like an institution of standardization. Since joining the museum in 2020, I’ve been engaged in a lot of curatorial work that explores museum reform and the reasons behind it. Yet, when we consider how change could be incorporated into the museum, we’re immediately confronted with the challenge of maintaining the status quo, which is, perhaps, a simplified way of describing conservation.

I invite you to recall the data I began with, and how, in the context in which we operate, this serves to highlight the ongoing forms of violence that occur within our modern art museum collections. Reform can be achieved through exhibition-making, experimenting with ways to recast artworks – beyond notions of autonomy and genius and towards a more convivial approach. Here, invoking ideas of public time or unchronological, regenerative time could involve placing works in close dialogue, allowing them to resonate with each other, for example; this could also involve dis- and re-assembling displays, challenging the linear narrative of art history that is often the default way collection displays are ordered.

Curatorially, my intention is not to disrupt our enchantment with canonized works, particularly when it comes to Western art; I’m not interested in fading this enchantment. Instead, I’m interested in unsettling the autonomy of the Western art project, which promotes a history of artistic geniuses. I do this by fostering conversations between works that challenge the established canon, and as I understand it, recasting isn’t about stopping the default recreation of hierarchies within collection structures. Instead, it’s about shifting the conditions of our engagement with the knowledge that history is negotiated. Many scholars discuss this kind of shifting, or recasting, but I keep returning to Karen Salt, a scholar of sovereignty, race, collective activism and systems of governance.3 She argues for the role of the reviser, one who shifts the terrain by moving away from becoming and towards the disorganized unfinishedness that we determine. This may not be a permanent fix for the hierarchies of the collection, but one of the first goals of revisioning is to reuse the tools around us to move the conditions. So, insertion and inclusion, yes, but on the terms that we determine.

I also want to say something about the decolonial strategy of inserting and including, which I’m also in a troubled relationship with. If we take the data of the male–female ratio – a formulation which is binary and highly problematic to say the least, but, as the saying goes, what we don’t measure, we don’t know – if we take this as an example, one correction strategy would be to acquire as many female-identifying artists as there are male-identifying artists in the collection. And that’s maybe a job of around ninety years, given the age of the collection. We don’t have this time, I don’t have this time. Moreover, I don’t think that strategic accumulation is the right measure, because it’s precisely the logic of capital that we’re trying to subvert; moreover, depot space is running out. But speaking in the context of the Climate Forum, we especially don’t have the luxury of time, or time to be this short-sighted either. It’s important to try and think of the collection in totality and to shift, a little bit, the conditions or the prism that we view works in or through.

That’s why this act of recasting artworks is so important. Speculative narratives, particularly those that blend revisionist history with predictive futures, offer unique perspectives. Unlike narratives that neither acknowledge the past’s tensions nor seek resolution, these narratives don’t aim to eliminate all contradictions and unevenness in pursuit of a fixed future. Instead, they suggest we embrace these challenges for a while. They’re actually saying, ‘Let’s stay with those challenges for a bit.’ If the promise of Francis Bacon’s [Fragment of a] Crucifixion (1950) or Guercino’s Andromeda (1648) is not yet fully realized, then the horizon of that political project is still necessarily open.

Dagmar Marant requested a reprint of Guercino’s Andromeda and invited workshop members to take cut-outs of the reprint as a way of collectively connecting to the painting. Van Abbemuseum, 18 November 2024. Photo: Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G: Thank you.

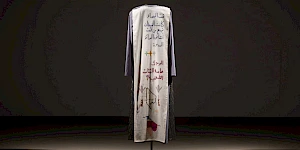

Yolande mentioned the different categories of case study that we’ve attempted to place works in. These are: ‘latent’, ‘the accumulative’, ‘artworks that are too big’, ‘the too fragile’… When the question of what could be put into the ‘latent’ case study was posed to the collection team, Guercino’s Andromeda was one of the artworks they immediately identified. It has never been shown before, which I find interesting. It’s not to say that it hasn’t lived a life, but let’s say it’s in an institution and hasn’t been let out, and essentially no one knows what to do with it. It was painted in the seventeenth century, and it was donated to the museum before it decided to follow the trajectory of becoming a modern art museum.

Yolande described this work as the outlier, which is a perfect description. I was interested in this case study in relation to what Yolande will speak about next – a high-stakes work. What happens when we think about life and death when someone like Francis Bacon comes into the picture? Everyone starts to get itchy feet. They are like, ‘OK, now it’s serious.’

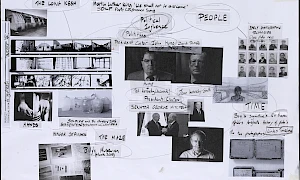

I’ve been working with the collection team and also other people in the team – the librarian, archivist, where I have posed questions about language and how you move through – or how you are meant to move through a museum when you think about life and death, as opposed to how you might be outside of it. I asked team members to bring in an object from their home that they were willing to let go of, playing with the idea of freeing something, allowing it to move on, as opposed to how Yolande was mentioning, how museums are taught to preserve everything until infinity, right? The responses have been astonishing – not ever anything that I’ve heard discussed before in the museum. They have been incredibly creative and poetic and artistic – if and when we started thinking away from the institution, what people would do, in terms of ritual or ceremony for a deaccession or a loan, was incredibly interesting. We are now proposing a dress rehearsal where we will be dining with said artwork and maybe, fingers crossed, with Francis Bacon alongside it. We will be dining next to these works and, at the end of our meal, attempting to create a ritual that we will share with one another.

YH: When I approached G to work as one of the four artist interlocutors that I mentioned, the invitational commission had two goals. The first part was to design what we’ve been calling a footnote or an appendix to the care and deaccession protocol, in collaboration with the collection team – that is, the team in charge of maintaining and caring for artwork. Their task, I would define as like ‘freezing’ works in time: trying to keep them in one material state so that they can last for forever – the mandate of the modern art museum. Of course, we know that’s impossible. How, then, do we contend with that impossibility? In order to answer this question and come up with appendix points that could be added to the usual protocols of care and maintenance, I invited G to think along; and that is what the workshops with the collection team are working towards. Part 1 is back-of-house work, domestic work, or the work that never actually comes to the fore. You don’t encounter this maintenance work when you visit a museum.

The second part of the invitation draws from G’s performance practice and presents that front of house. When we were thinking about death/life cycles in relation to artworks, the idea of throwing a birthday party or funeral ceremony which is present in G’s work came to mind. The question is, how do we visualize death/life cycles? The invitation is for G to think of a score that she and others will eventually perform, and that can facilitate a birthday party or a funeral. G talks about how these are two sides of the same coin. The dress rehearsal with the collection team is us figuring out quite practically what that might feel like and look like.

To close out, we can spend a few minutes thinking about the other case study out of the six that we have, namely what we’ve called the ‘high stakes’ category. When we consider our seventeenth-century friend [Andromeda], the stakes seem low. But something changes when we look at a recognizable work from the canon, like Francis Bacon’s Fragment of a Crucifixion. In the above images of G at the Van Abbe, both G and Bacon’s Crucifixion depict two figures: some interpret them as human, while others see them as animals in struggle. The upper figure, possibly a dog or a cat, crouches over, possibly at the point of a kill. The lower figure resembles a crucified Christ but is too small to hang on the cross. Thinly sketched passersby appear oblivious to the central drama. Bacon made several paintings on the theme of crucifixion, believing that so many beautiful paintings of the crucifixion in European art serve as a fantastic peg to hang various feelings and sensations. When reading about Bacon’s intentions behind the painting, I was surprised to relearn that part of what is at stake in this piece is the act of producing an icon of crucifixion to peg new ideas on it. The practice of recasting, I believe, works similarly, which suggests I may be more of an art historian than I thought – this is deep art-historical work. Bacon didn’t paint the crucifixion to promote religious themes, but he had a certain agony or fear around death that you see in his paintings. One reading of his paintings is as an attempt to escape this destiny. Ironically, this work we’re trying to bring closer to death is a work that actively tries to escape it.

When preparing our workshop, our art handler colleague Toos Nijssen discovered that the work’s frame wasn’t made by Francis Bacon. This revelation allows us to display the painting without the frame. Initially, the painting and frame were attributed to him, but this isn’t the case. Toos realised this while conserving the painting, which needed mould removal. Frames and glass protect the work from degradation, preventing it from being exposed to the elements and catching parts of the cotton pieces in the work should they fall. For this collection display, we are considering showing the painting without a frame, exposing it to natural disintegration. This challenges the tendency in collections to ward off death and offers a shift in thinking.

There’s a clear tension between death or disintegration and conservation practices. Addressing death requires confronting value systems around capitalist accumulation and maintenance. Thinking about heritage also requires considering how its construction as a system of shared beliefs has been made possible through the destruction of other worlds and values, such as by removing existing settlements – purifying monuments or curating life – challenging universalism and anthropocentrism in world and heritage. Even removing a frame raises questions about a work’s universality and its intended audience. Who’s the ‘we’ being served?

I’m drawing from Rhania Ghosn, a social professor of architecture and urbanism at MIT, and El Hadi Jazairy, with whom she co-authored Climate Inheritance.4 I’m interested in how Ghosn and Jazairy approach World Heritage sites as narrative devices that facilitate the process of figuring out and outlining. They draw from Donna Haraway’s concept of ‘string figures’ as a way to engage in continuous unfolding and reweaving, challenging the assumption that the world cares about or should care about a World Heritage Site. Climate crisis conversations often speak about an ambiguous ‘we’, implying a shared future where everyone might be served. Uncommoning histories and futures involve uncommoning the ‘we’ of the world in climate response. Private interests like Henri Van Abbe’s have come at significant public costs, and if we don’t ask who’s behind the ‘we’ of the world in climate response, solutions may perpetuate similar systems of dispossession.

Reframing collection displays as a way to think about regenerative time is part of our approach to shifting the conditions under which we view, accumulate and conserve works. We’re trying to connect past oppositional practices to present resistance as part of a continuum. This is why working with collections is important: it’s one way to address the future. Part of shaping just futures involves rescuing the future from its own utopian promises. This work is possible within the framework of a collection display of modern art, where we can do this by situating moments of transformation and revolution within the past, contaminating the future with ghosts.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

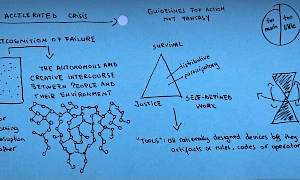

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

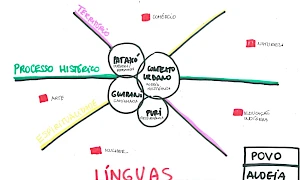

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations