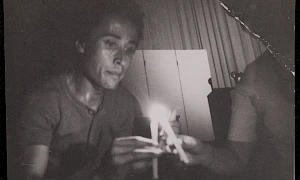

Milad: The Birth of a Dream and Its Continuation

Translator and writer Sanaa Salameh remembers her husband Waalid Daqqa, the novelist, educator and political prisoner of 37 years, who died in an Israeli prison last year. The text was originally published in Majallat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya (issue 139, summer 2024) and has been translated from Arabic by Jude Taha.

Walid taught me, through his patience and unwavering strength, how to cultivate the most profound connections and safeguard the most sacred ones. He showed me how to breathe amidst the polluted air of an era defined by national and moral decay, how to remain ethically alive, and how to lead a life motivated with meaning and purpose, even in a world that has reduced human worth to that of a disposable cup. Yet, for all I learned from him, he often told me that I had taught him something even greater – that love is as essential as freedom. In his Letter to a Companion, he described me as the ‘al’ – the defining article – in his life.

Our life together was never easy, Walid, but it remains unlike any other. Everything we have taken from this world, took from us, giving everything a unique meaning. Every phase of our journey is a story worth telling – stories we share with ourselves and with others. The crown jewel of these stories is Milad.

Though Milad and I must now navigate this difficult life alone, carrying only your memory, you will always remain our first teacher. We will follow your path and pursue your dreams. We will continue to dream, for dreaming is a beautiful act – it magnifies our strength to face life’s challenges and complexities. Many fear dreaming, confronting it as if it were a nightmare. But Milad and I will dream boldly, without fear, because the worst that can happen is waking up – ready to face reality, clear-eyed and aware.

I remember my first visit to Walid as though it were an extension of the visits I used to make to my father during his imprisonment in the 1970s. Back then, we referred to ten-year sentences as ‘short periods’, a grim concession to the decades our prisoners now endure in Israeli prisons. Through my father, I came to know the icons of the prisoner's movement, those who spent countless years in captivity, like the martyr Omar Al-Qasim. Little did I know then that my life would become intricately connected to a prisoner whose journey would so closely mirror that of Omar Al-Qasim.

Walid, both a martyr and a witness, remains in my memory. I recall his unwavering moral integrity and remarkable politeness during that first visit, which I initiated to better report on the prisoners directly. Out of courtesy, I asked him, ‘What can I bring for you (all), Walid? Is there something you need?’. Without hesitation, he replied, ‘Yes, yes, please bring me the book The Israeli Military Mind’. From that day forward, books became Walid’s foremost request. At the start of every visit, his first question was always, ‘Did you bring books?’. Over time, after Milad’s birth, this question evolved into something more tender: ‘Did you bring photos?’.

My prison visits became sacred rituals, each one marked by meticulous preparation and lingering reflections afterward. The energy, hope, and determination that Walid infused in me were unparalleled. Each visit was divided into two parts: the ‘work visit’ and the ‘hope visit’. The work visit was filled with discussions of instructions, plans, and activities to support the prisoners’ cause from within the prison walls. I do not recall Walid ever speaking only about himself or his own conditions; his focus remained steadfast on the collective – on the prisoners, the prisoner movement, broader political and national issues, and even the state of the larger Arab world.

I vividly remember visiting him in Gilboa Prison during the Egyptian revolution, after he had already endured 25 years of incarceration. With unshakable resolve, he told me, ‘If spending another 25 years in prison is what it takes for the Egyptian revolution to succeed, then I am ready.’.

As for the hope visit, which focused on Walid’s eventual freedom, it remains unfinished to this day.

Days turned into weeks, weeks into months, and months into years. Together, we created countless memories, too many to recount here. Through it all, Walid remained steadfast in his struggle both within and beyond the prison walls. He dedicated himself to grappling with the most difficult questions and seeking even harder solutions for the Palestinian national movement. Walid continued to write, to nurture hope, and to cling to the unyielding dream of freedom and liberation.

Yet Walid was abandoned by the very national movement he devoted his life to, forgotten by those for whom he sacrificed everything. I still recall the piercing cry I delivered in Ramallah on May 8, 2023, during a speech commemorating the 21st anniversary of national leader Marwan Barghouti’s imprisonment. My words were directed at the Palestinian Liberation Organization, the national and Arab movements, and all supporters of Palestine worldwide. Today, I repeat that cry: I demand the release of Walid Al-Sharif's body so it may rest in the sacred soil of Palestine, not remain imprisoned in the cold, oppressive refrigerators of the occupation.

Must the prisoner wage the battle for freedom alone? Must his family shoulder the burden of securing his release – or even just his body – on behalf of the entire national movement? How can we justify a prisoner languishing in captivity for four decades if not as a result of betrayal? What is more unbearable: the silence of the betrayer, or the anguished cry of the betrayed?

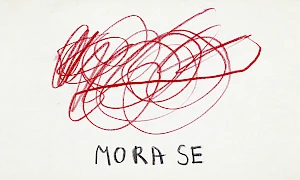

At that time, I stood before the Palestinian leadership in Ramallah and screamed, and I continue to scream the words Walid could never write and will never write – words lost to the illness, exhaustion, and betrayal that consumed him during his long, cursed wait... until martyrdom claimed him. My words were as stark as Walid’s plight, as the plight of all prisoners of the Palestinian national movement. As stark as captivity, as stark as freedom. As stark as martyrdom, and as stark as the martyr himself.

Walid joined the struggle as a member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine in 1983. He was arrested on March 25, 1986, and, in March 1987, sentenced to life imprisonment by the military court in occupied Al-Lydd. In 1998, Walid and a group of his comrades from Jerusalem and Palestine 1948 officially joined the National Democratic Assembly Party, though they had been actively involved with it prior to that. Despite being abandoned by their national movement and enduring the depths of prison, these individuals never ceased their struggle within its ranks.

In 2012, Walid’s life sentence was set at 37 years, meaning his release was scheduled for March 24, 2023. However, on May 28, 2018, the military court in Beersheba issued an unjust ruling, adding two more years to his sentence under the pretext of his involvement in smuggling mobile phones to facilitate communication between prisoners and their families. As a result, his new release date became March 24, 2025. And given the slim chances of repealing the Zionist law that prevents early release for prisoners like Walid – even for medical treatment, unless granted clemency by the state president — his family began pursuing legal avenues to challenge the additional two-year sentence and to request a one-third reduction of this extended term.

In the final chapter of Walid's illness, as the walls of his captivity tightened and the Palestinian national movement faltered, his family found itself nearly alone in their struggle. On March 28, 2023, they launched the ‘Campaign to Release the Prisoner Walid Daqqa,’ rallying the support of thousands of Palestinians, Arabs, and advocates for justice and freedom worldwide. The campaign’s sole objective was clear: ‘the immediate release of prisoner Walid Daqqa to allow him access to unrestricted medical treatment.’

Yet, this goal was cruelly thwarted. The racist Zionist judicial system denied justice, solidarity protests faced brutal repression, campaign content on social media was censored, and a torrent of malicious rumors sought to undermine their efforts. Undeterred, the family worked tirelessly to refute these falsehoods. During this time, prisoner leader Zakaria Zubeidi rose up from solitary confinement and submitted an urgent request to donate bone marrow to his brother-in-struggle, Walid, declaring himself a comrade ‘to the bone’. Yet others hesitated, and tragically, all attempts failed.

The shocking, unofficial announcement of Walid's martyrdom came on April 7, 2024, transforming the campaign from one for his release into one for the liberation of his corpse.

Walid Daqqa was always a unifier, a relentless critic of wrongdoing, whether within his organizational framework, the PLO, or the broader Palestinian national movement. Today, we do not seek to overshadow Walid’s voice, but we have the right to ask: how could he be excluded from prisoner release deals and exchange agreements not once, but four times – in 1994, 2008, 2011, and 2014? What did every individual and leader in his national movement do for Walid Daqqa, whose body remains detained alongside his comrades? What have they done, and what will they do, for the sick prisoners and all those still languishing in enemy prisons? How will they confront Walid’s memory, knowing they failed to secure his freedom in life?

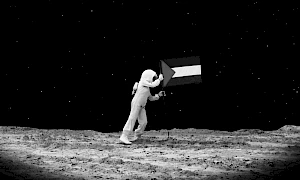

Walid wrote extensively about resistance – the resistance in Jenin, the resistance against the erasure of consciousness, and the resistance to the ordinary and parallel time imposed on prisoners’ bodies. Even in his children’s trilogy, he centered his stories on prisoners, refugees, and martyrs, yet he steadfastly refused to write about death. Instead, he wrote a play about martyred prisoners, The Martyrs Return to Ramallah. Time and again, we called for Walid not to be left alone, for his prophecy of returning as a martyr to remain unfulfilled. We urged that he must not end up like the characters in his play, whose spirits returned to Ramallah to inscribe on the walls of authority buildings: ‘Free the martyred prisoners. Liberate the prisoners’ remains.’

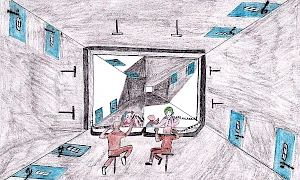

On March 25, 1986, Walid Daqqa founded a university unlike any other in the world – a university whose branches now extend across 28 locations in northern, central, and southern occupied Palestine: 19 prisons, 4 interrogation centers, 3 detention centers, and 2 military courts. This institution spans the entirety of historic Palestine, covering 27,027 square kilometers, unimpeded by checkpoints, as if one owns the entire land with no one to stop them.

Nothing could stop Walid – not even his martyrdom, which was unofficially announced on April 7, 2024. He remained steadfast, as he said to me and a comrade in a recorded call before the war of extermination on Gaza and Palestine: ‘I will not let them write the final line.’ True to his words, he continues his struggle even after his physical absence through three texts: a novel, a play, and an intellectual study, published in the special issue of the Journal of Palestinian Studies, where he served on the editorial board.

We will continue, alongside those who carry Walid’s legacy, to protect, amplify, and translate his vision into action through a precise programme that honors his body of work, just as Walid intended and as befits him and Palestine. Walid’s spirit still fights, and his presence lingers, even as his body remains unjustly and unlawfully detained.

Walid Daqqa continues to defend us – his people’s cause, the prisoners’ cause, and the cause of freedom and liberation.

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

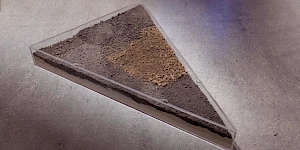

The Soils Project

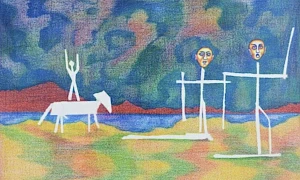

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

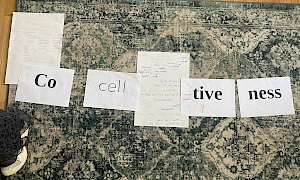

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

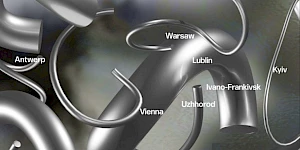

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

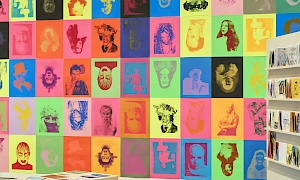

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

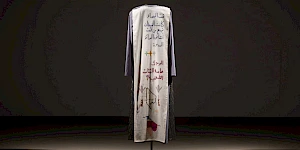

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

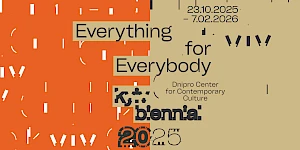

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

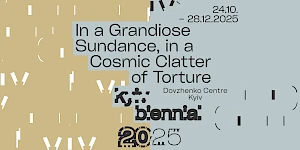

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

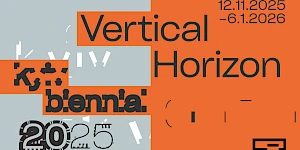

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations -

Translated into Socialism: An experiment in internationalism

Merve Elveren, Tevfik Rada, Sezgin BoynikInternationalisms