Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

In this paper, researcher Mine Yıldırım charts the history of street dogs in Istanbul, from 1910 to the present. Structured through five episodes, the text spans the conditions that determined the life and death of dogs, practices of care and resistance and the wider dynamincs of human-animal relations. ‘Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul’ was presented in exhibiton form as part of ‘Lives of Animals’ at Salt Beyoğlu (April - August, 2025).

Two opposing yet inseparable forces shape the lives, movements, bodies, and health of Istanbul’s street dogs and their relationships with humans and other non-human inhabitants: care and violence. This tension defines their births, illnesses, and deaths, underscoring the fragile balance between these conflicting but interconnected dynamics. On one side, violence manifests itself as the state’s destructive power over street dogs, exercised through local governments and fluctuating in intensity over time. Spatial regulations increasingly restrict the freedom of these animals, reinforcing a politics of displacement, isolation, and extermination. Policies and narratives dictate where, how, and under what conditions they should live and die. On the other side, care emerges as a quiet but persistent resistance to state-imposed violence, rooted in the profound affective bonds between humans and animals. Simple yet widespread daily acts sustain and protect street dogs, allowing them not just to survive, but to live. Despite the growing systematization of violence, care and compassion for animals remain the primary force that enables their continued presence in the city, fostering coexistence in defiance of violence.

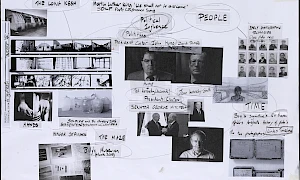

‘Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul’ is the title of a long-term research project encompassing my PhD, a recent exhibition at Salt Beyoǧlu (Istanbul), and a forthcoming book. The research explores affective and political landscapes that shape the lives of Istanbul’s street dogs. Tracing its origins to the 1910 Hayırsızada Incident – when over 80,000 street dogs were exiled to Sivriada, the city’s smallest and most remote island, and left to die – the study examines the ongoing interplay between care and violence. Archival documents and firsthand accounts reveal how these opposing forces have continuously shaped one another. ‘Between Care and Violence’ investigates the persistence of decanisation policies, their contradictions and reversals, and the progressive restriction of street animals' spaces and freedoms despite a longstanding culture of care and protection.

Mine Yıldırım, ‘The Lives of Animals’, Salt Beyoǧlu, Istanbul, April 2025, photograph

‘Between Care and Violence’ maps the politics of decanisation in Istanbul across five key historical episodes from 1910 to the present.1 It analyzes the shifting discourses, affective regimes, spatial policies, and legal frameworks that have shaped the existence of these resilient yet vulnerable creatures. Beginning with the 1910 deportations – which dismantled the city’s deep-rooted tradition of canine care – it traces evolving mechanisms of violence, charting their transformation over time.

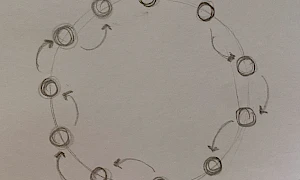

The ‘episodes’ that mark turning points in the trajectory of decanisation politics cannot be reduced to a linear or progressive narrative or confined to a fixed, segmented timeline. Instead, they reflect multidimensional, complex, and interpretive processes, most importantly encompassing the foundational, non-dialectical tensions between violence and care. These episodes unfold through interwoven dynamics, shaping and reshaping one another, revealing a historicity rooted in the here and now, marked by continuities, ruptures, and returns.

‘Between Care and Violence’ uncovers how notions of care evolve in response by examining the emotional intensities stirred by violence against street dogs. It presents a dual narrative, intertwining the changing concept of care – which both influences and resists shifting forms of violence – with the broader discourse on rights and justice. This framework reveals how animal welfare policies and rights shape – and are shaped by – the conditions under which dogs live, interact with humans, and ultimately die.

EPISODE I

In the Wake of the Catastrophe

The birth of decanisation politics: Shifting registers of proximity, compassion, and care for street dogs

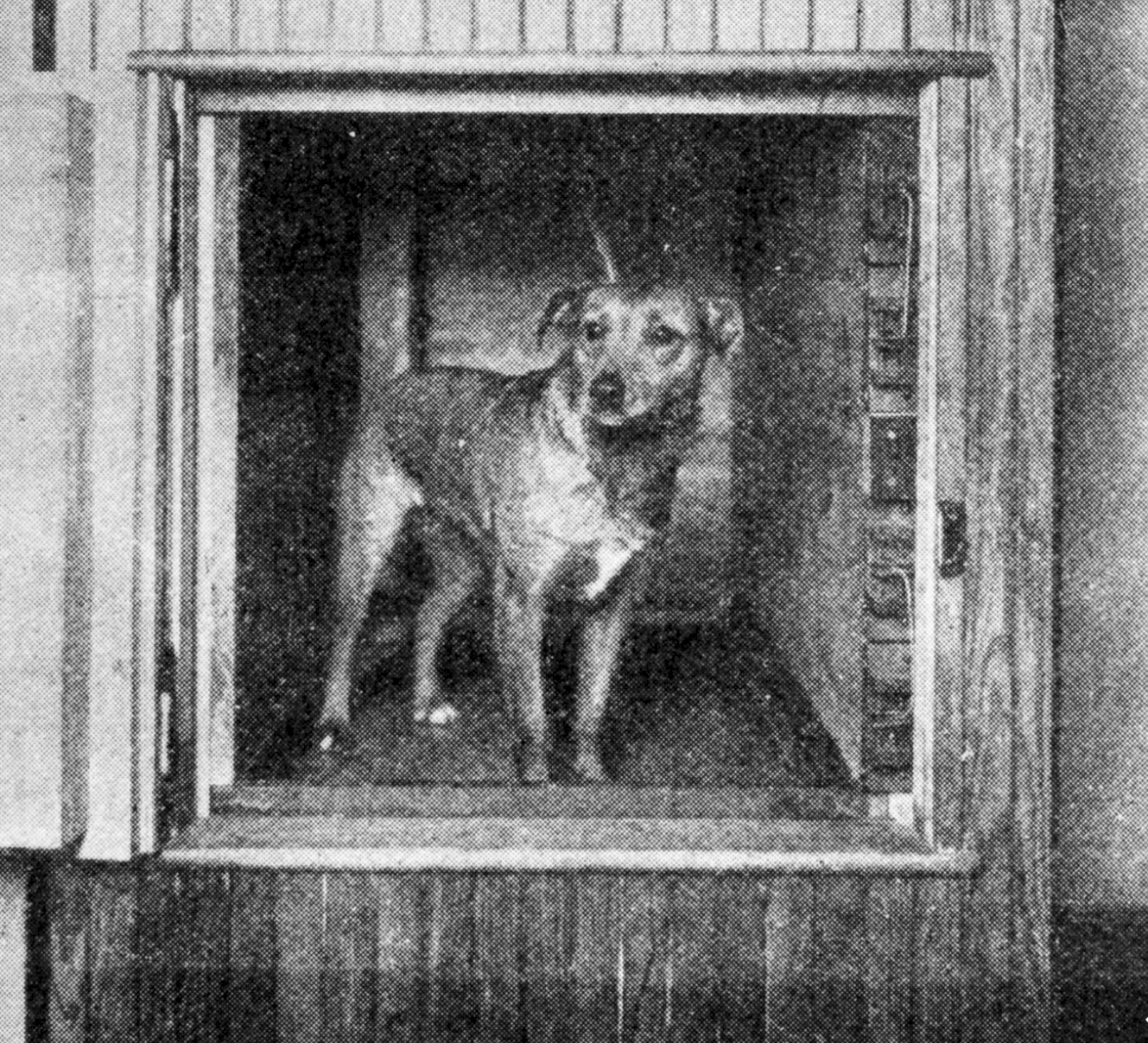

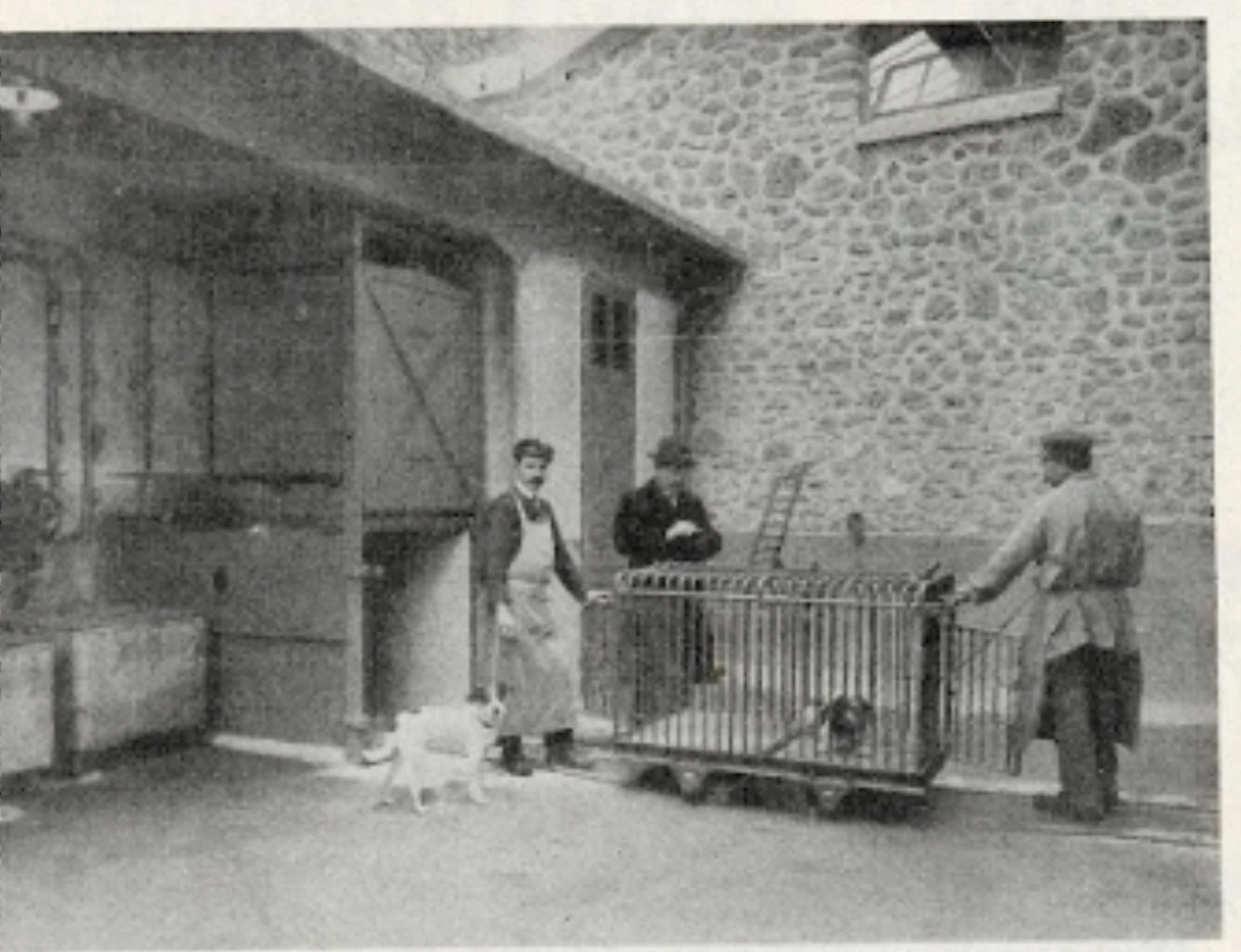

Capture of Stray Dogs, 1910, photograph, Pierre de Gigord Collection

Jean Weinberg, Street dogs exiled to Hayırsızada by the Young Turks, 1910, photograph

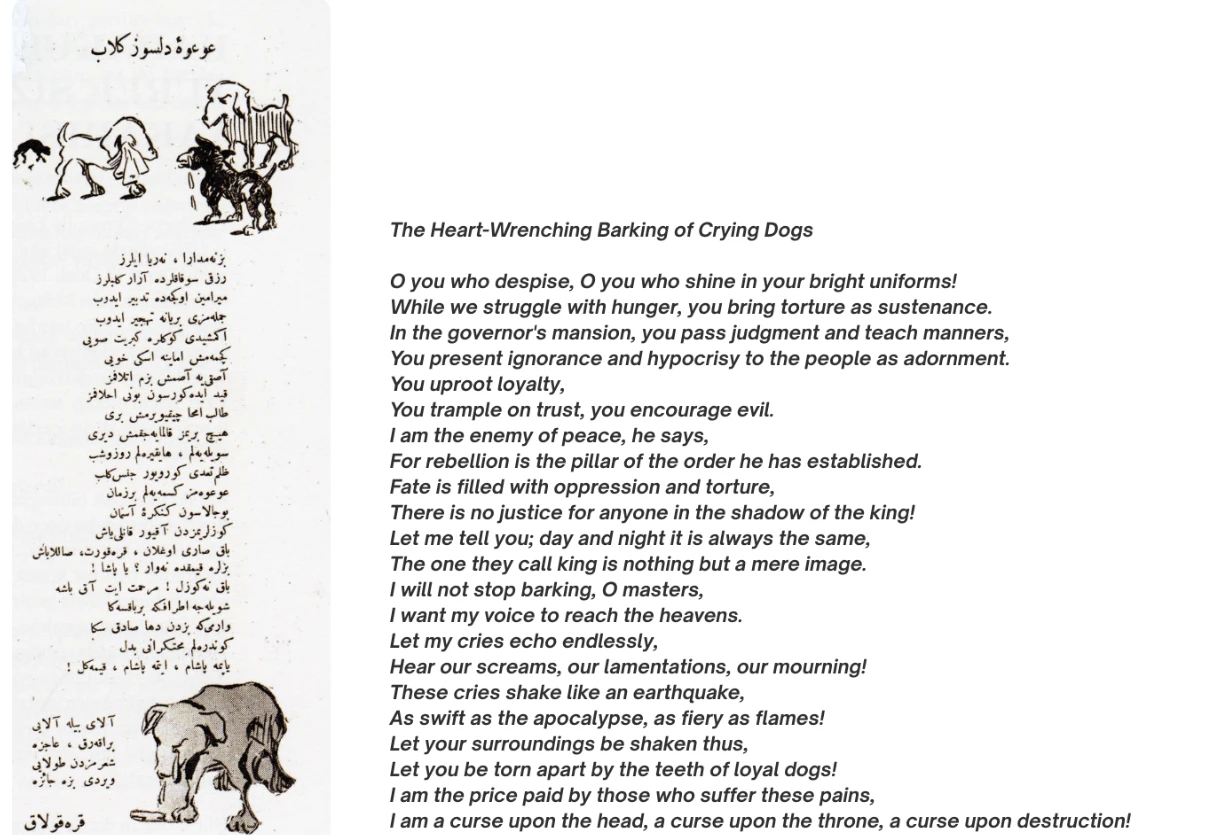

Kara Kulak, Illustration in Alay, no. 2, 1920, print illustration

Violence | Fear of Disease

Following the exile and abandonment to death of over 80,000 dogs on Oxia in 1910, both the violence directed at street animals and the care shown toward them became shaped by a single, overwhelming emotion: fear.

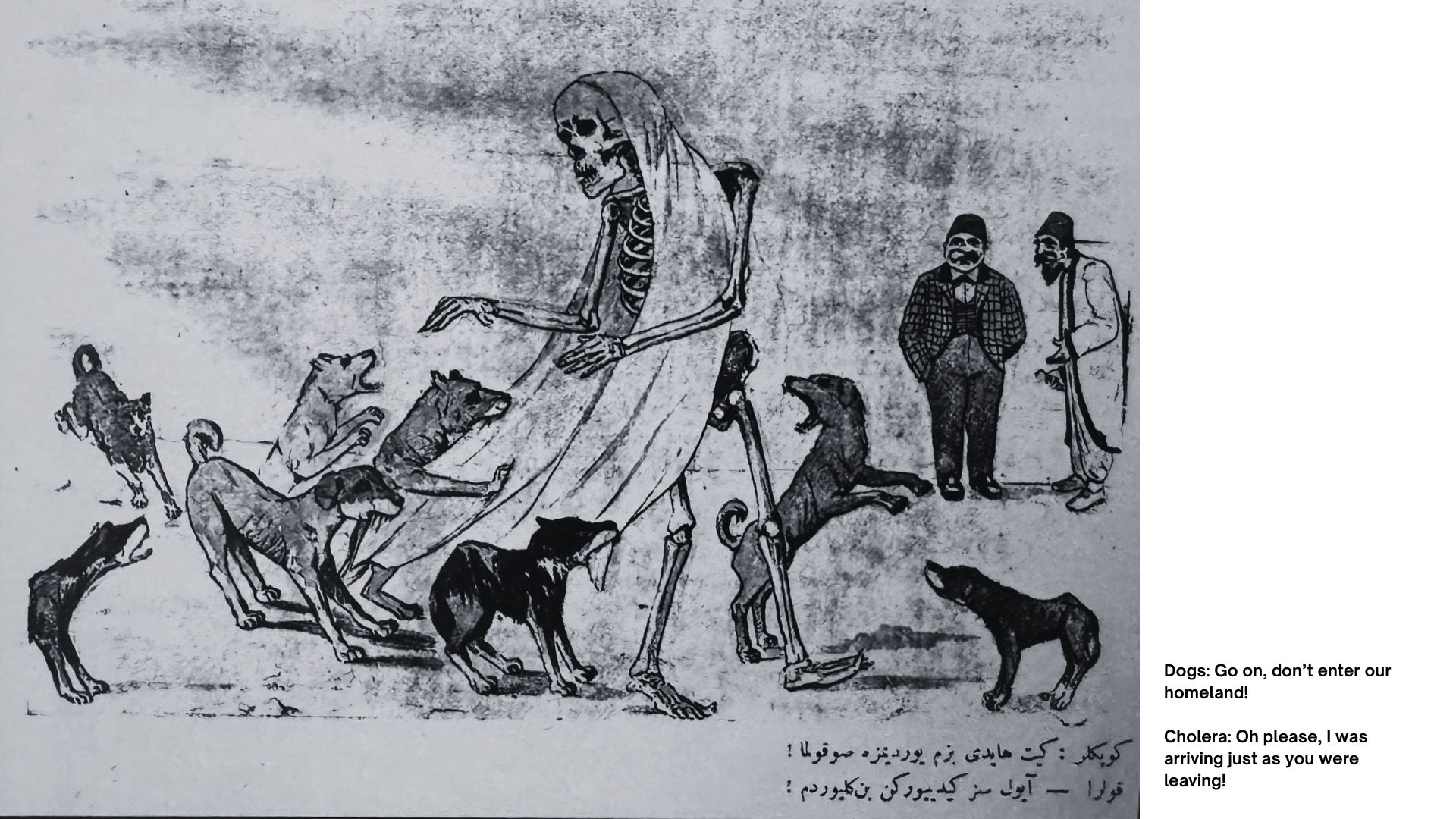

This fear stemmed from haunting images and anxieties – that tens of thousands of starving, sun-scorched, and desperate dogs, driven mad or drowning as they leaped into the sea after every passing boat, would wash up on the shores of the Bosphorus; that the stench of their decaying corpses would pollute the city; or that the waters of the Marmara Sea, which consumed them, would contaminate Istanbul’s drinking water and poison its residents. Added to these visceral anxieties was a mounting panic over disease: cholera, rabies, and contagion became synonymous with the presence of dogs.

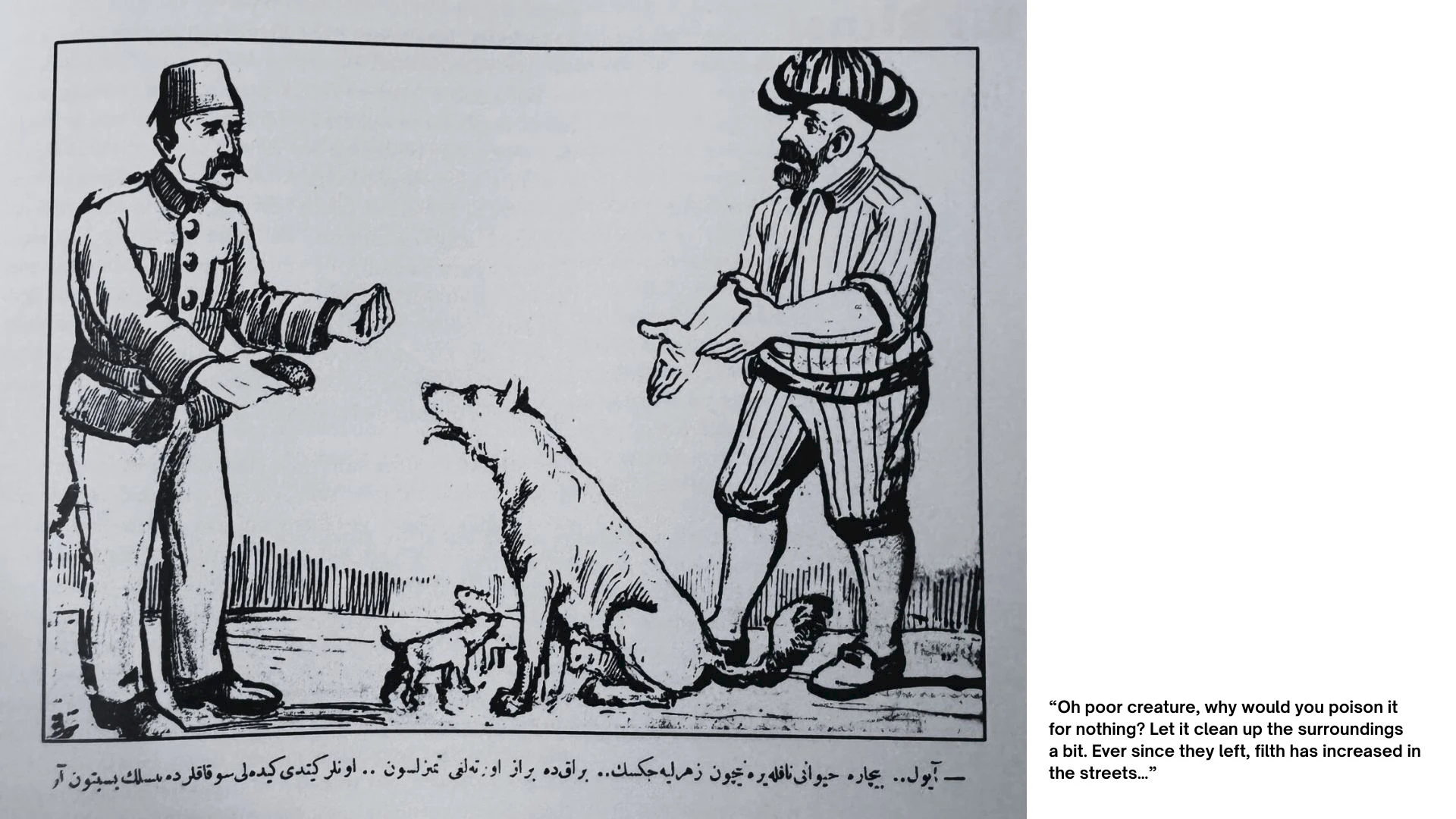

Unknown artist, Illustration in Yeni Geveze, no. 70, 1910, print illustration

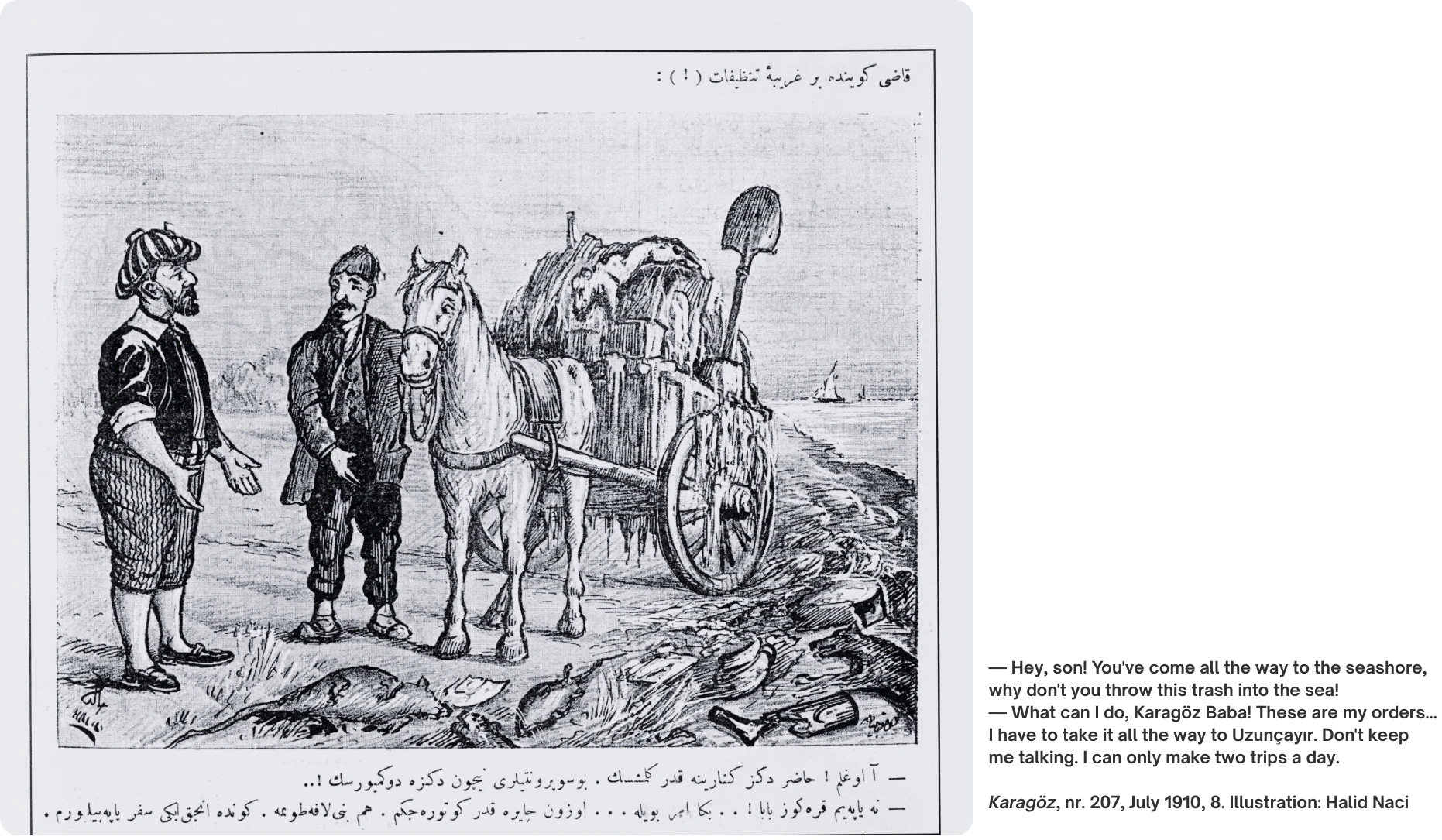

Halid Naci, Illustration in Karagöz, no. 207, 1910, print illustration

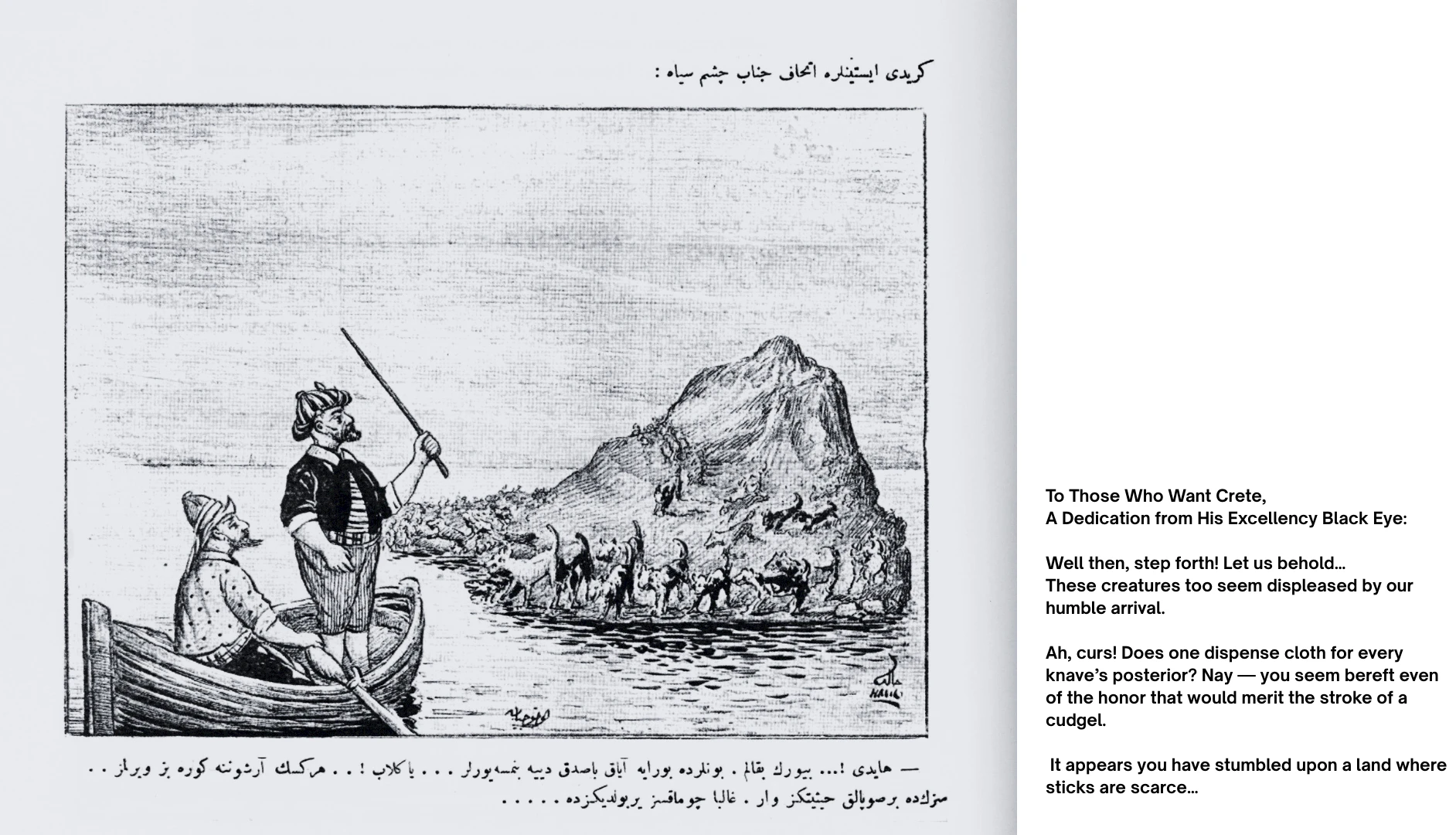

Utucuyan, Illustration in Karagöz, no. 207, 1910, print illustration

Unknown artist, Illustration in Karagöz, no. 312, 1911, print illustration

The most profound consequence of this fear was a transformation in the methods and spatial politics of dog control. After the ‘Hayırsızada Incident’, authorities no longer sought to remove, deport, or exile dogs from the city. Instead, they were killed wherever they were found. Once perceived as companions embedded in the fabric of urban life, street dogs were now reimagined as filthy, dangerous, disease-spreading creatures whose extermination became not only acceptable but necessary – and this violence unfolded publicly, in full view of the society that had coexisted with them for centuries.

Care | ‘Pets’ vs. ‘stray’ dogs

Mass dog exiles in 1910 ultimately failed in its goal of eradicating Istanbul’s street dogs; by 1912, Mayor Cemil Pasha was still lamenting their presence on the streets. Yet the mass displacement and abandonment of dogs on Istanbul’s smallest and most remote island – where the whimpering, barking, and howling of tens of thousands of animals echoed along the shores of the Marmara Sea – marked a profound rupture in the relationship between the city’s people and its canine inhabitants. This event shattered a longstanding culture of care, triggering a fundamental shift in the meanings, emotions, and practices surrounding dogs’ lives.

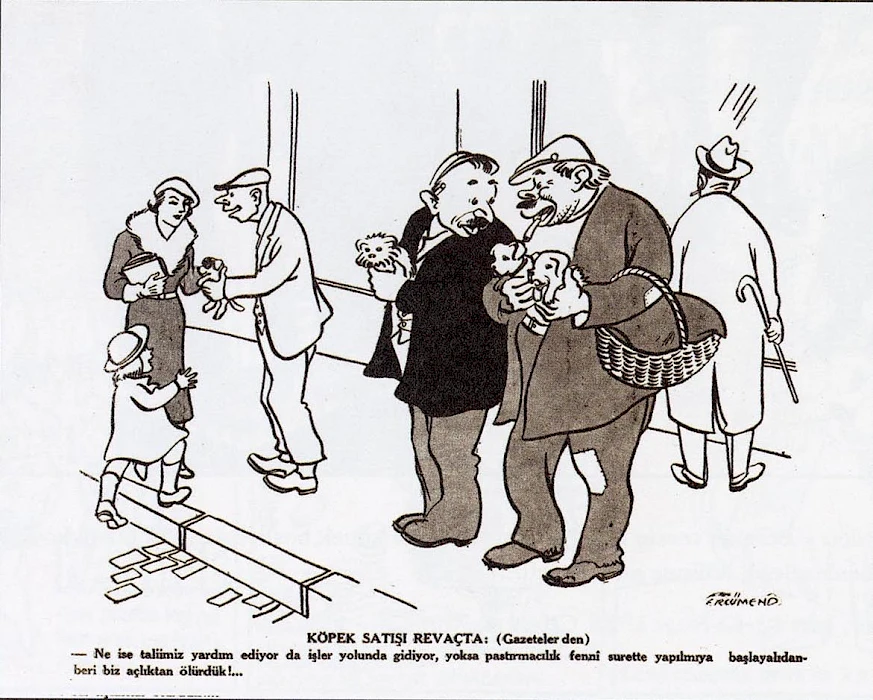

Ercümend, Illustration in Karikatür, no. 100, 1937, print illustration

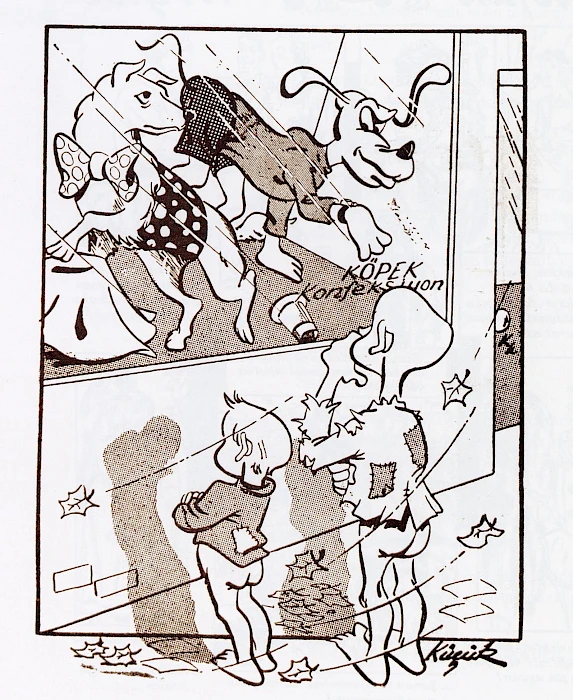

Unknown artist, Illustration in Papağan, no. 8, 1968, print illustration

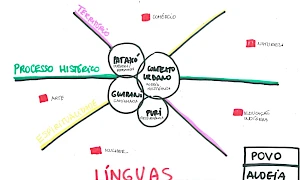

Rumors of cholera, suspicions of rabies, and press-fueled fears intensified during this period, altering perceptions of dogs and redefining their place in the city and in people’s hearts. Practices of care, protection, feeding, and cohabitation that once expressed closeness, compassion, and belonging gave way to new classifications that marginalized street dogs. Increasingly, dogs were labeled as ‘stray’ and ‘ownerless’, while a Westernized ideal of domesticity emerged – framing ‘acceptable’ dogs as purebred pets, tied to private households, class distinctions, and modern urban life.

A new binary took hold, one that remains foundational to violence against animals in Turkey today: the distinction between ‘pets’ and ‘masterless’ animals. Street dogs, once integral to Istanbul’s social and urban fabric, became recast as ‘strays’ contrasted with ‘domestic’ companion animals that embodied bourgeois values of civilization, modernization, and privatized care. This discursive division continues to shape human-animal relations in the city and underpins contemporary debates about the presence and treatment of animals in urban space.

EPISODE II

‘Slow Eradication’ vs. ‘Swift, Painless, and Scientific Culling’: Euthanasia debates, ‘stray dog problem’, fear of rabies

Violence | ‘Stray dog problem’ and mass dog culls justified by rabies

Alongside the growing distinction between owned and ownerless dogs – a reflection of shifting notions of property, private space, and the redefinition of dogs' presence, movement, and interaction with humans in public spaces – another term gained prominence: ‘stray’ dogs. The Turkish term ‘başıboş’, the equivalent of the English ‘stray’, erased dogs’ local embeddedness, settlement patterns, and cultural, historical, and urban roots. It disrupted the symbolic and linguistic framework in which dogs had once been seen as neighborhood residents, instead recasting them as rabid, unruly, dangerous beings in need of elimination. The justification was already in place, reinforced by the most horrifying images seared into the public imagination – rabies outbreaks, vicious dog attacks, and deaths.

Tülay Divitçioğlu, Street dog culling scene, 1979, photograph

The method of dog elimination had shifted. No longer reliant on mass displacement or forced deportation, it now took the form of ‘gradual extermination’ and ‘on-site killing’. Amid escalating rabies hysteria, fueled by the press, Cemil Topuzlu – who served twice as Mayor of Istanbul – recalled in his memoirs: ‘At the time of my appointment, I found nearly thirty thousand dogs. I had them exterminated slowly.’ During this period of ‘slow extermination’, and for decades afterward, municipal and police teams routinely executed dogs in the streets – either by shooting them with firearms or feeding them poisoned meat. Violence had been normalized, woven into the fabric of everyday street life. Culling was not just accepted; it was celebrated, one of the most publicized and proudly reported municipal activities in the newspapers.

Care | The Emergence of ‘Euthanasia’ Debates in Istanbul – Decanisation by ‘Swift, Humane, and Scientific Methods’

Euthanasia: ευθανασία, meaning ‘good death’.

(ευ, eu, ‘good, beautiful’; θάνατος, thanatos, ‘death’)

As the public grew accustomed to witnessing ownerless dogs being killed on sight, the discourse shifted – not toward improving their ‘good lives’ but toward ensuring their ‘good deaths’. The widespread fear of rabies gave rise to the rhetoric of ‘humane and scientific methods of culling’, promoted by the Society for the Protection of Animals (Himaye-i Hayvanat Cemiyeti) – Türkiye’s first animal rights association, founded in 1912 in response to the Hayırsızada deportations.

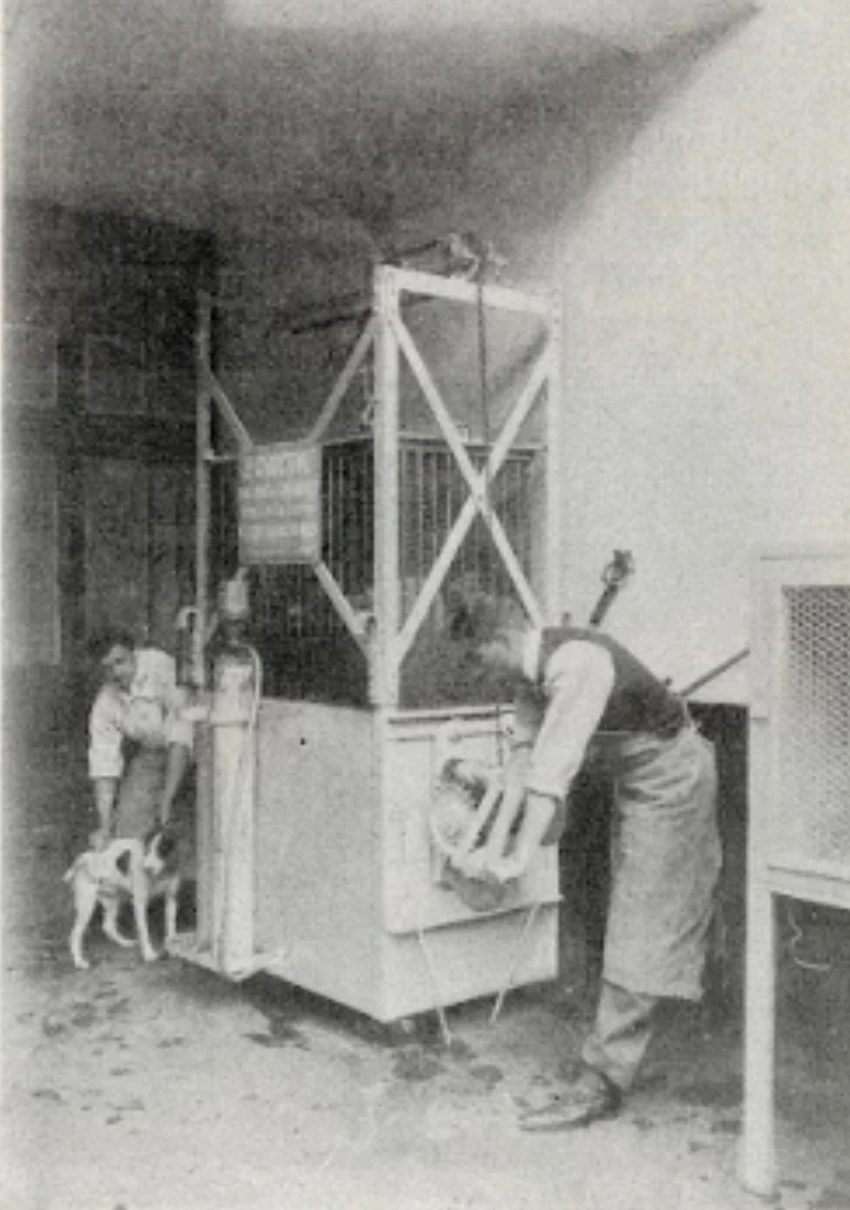

Jacques Boyer, Electrocution machine used to kill dogs with electric current, 1923, print illustration in La Nature

Jacques Boyer, The last hour of the condemned!, 1923, photograph in La Nature

Jacques Boyer, Cynoctone, a device used to asphyxiate dogs with compressed carbonic acid, 1923, print illustration in La Nature

The concept of euthanasia, now understood as the use of sedation and lethal injection, began to form the technical and medical infrastructure of decanisation politics in Istanbul. Gas chambers using coal gas or carbon dioxide? Electrocution systems? The exact methods remain uncertain. What is clear, however, is this: The Society for the Protection of Animals, which condemned the public shooting of dogs and the poisoning of meat as ‘barbaric,’ also endorsed municipal efforts that resulted in the annual killing of thousands of street dogs. Their concern was not how to improve the lives of street dogs but how to ensure their ‘good deaths’. The dominant question was no longer how they could survive but where and how they should die.

EPISODE III

Confronting stray animal shelters and carceral decanisation:

The Making of Animal Protection Law in Turkey

Violence | The birth of “stray animal shelters”

The Society for the Protection of Animals (Himaye-i Hayvanat Cemiyeti), the first animal protection society in Istanbul, voiced sharp criticisms against the ‘outdated scenes’ of dogs being shot or poisoned in the streets. Yet, their simultaneous efforts to develop faster, less painful, and more scientific methods of killing animals inadvertently laid the groundwork for a new spatial, visual, and testimonial politics of violence against animals.

By the early 1990s, a new spatial model emerged, one designed to isolate street dogs from urban life and, conversely, to shield urban residents from their presence. This marked the beginning of a new phase in the politics of dog removal: ‘home for the stray animals.’

İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality Kısırkaya Stray Animal Care Center, 2017, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Küçükçekmece Municipality Treatment and Rehabilitation Center for Stray Animals, 2024, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Bakırköy Municipality Stray Animal Care Center, 2012, photograph Mine Yıldırım

İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality Hasdal Stray Animal Rehabilitation Center, 2014, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Promoted under the slogan ‘a home instead of extermination’, shelters were introduced as the primary mechanism for managing the street animal population. Yet, in reality, these spaces became the command centers of violence against street animals and the epicenters of dog removal policies. Across Istanbul and throughout Türkiye, municipal authorities increasingly relied on shelters as tools of exclusion, control, and eventual disappearance.

Care | Reckoning with impunity and isolation: The making of the Animal Protection Law

In the print media, shelters were framed as safe havens – places where dogs would be fed, vaccinated, and neutered, shielded from suffering. This narrative sought to pacify public concern over the mass removal of dogs from the streets and to defuse social backlash against the ongoing violence.

However, it wasn’t long before the true nature of shelters was exposed. Reports and images surfaced nationwide, revealing suffering, hunger, disease, neglect, beatings, and torture in these spaces of isolation. Dogs were no longer simply wandering the streets; they were forcibly collected by municipal sanitation teams and confined in shelters – out of sight, beyond public concern, and inaccessible to intervention. These shelters functioned as centers of control, restriction, and discipline rather than care.

Throughout the 1990s, Istanbul residents witnessed firsthand the mass collection of dogs, the poisoning of tens of thousands during and after the 1996 United Nations Habitat II summit, and their execution with air rifles known as ‘tüf tüf’. No longer were dogs shot in public spaces, creating ‘outdated’ scenes of violence; instead, they were killed behind closed doors.

Neither stray, nor dangerous, unowned or vagabond. The dogs of Istanbul are street dogs.

What enabled the spatialization of dog removal, the unchecked violence in shelters, and the mass collection of street dogs was the absence of legal protection for street animals in Türkiye. Violence against street dogs was not punishable by law.

In response to this institutionalized violence – both in shelters and in society – the politics of care began shifting toward legal reform. The struggle to secure animals’ right to life in law became central. The enactment of the Animal Protection Law No. 5199 in 2004 marked a turning point for the animal rights movement. It was a milestone in the fight for legal recognition and a direct response to the systematic capture, confinement, and killing of street dogs.

EPISODE IV

Living and Dying on the Roadside:

Mass dog exiles and abandonment revisited

Violence | Transcarceral Geographies of Isolation and Exile in Istanbul

The Animal Protection Law, enacted in 2004, legally protected the lives and habitats of street animals for the first time. Article 6 empowered local governments to neuter, vaccinate, and administer medical treatment to street animals. Crucially, it also mandated that animals be returned to their original locations, ensuring they could continue to live in their natural environments rather than face indefinite confinement in shelters.

In Istanbul, the ear tags worn by street dogs serve as visible markers of identity, conveying three key pieces of information: first, they indicate that the dog has been neutered and vaccinated. Second, the color and shape of the tag indicate which municipality performed the medical intervention. Third, the tag shows which district affiliation marks where the dog ‘belongs’ within the urban fabric.

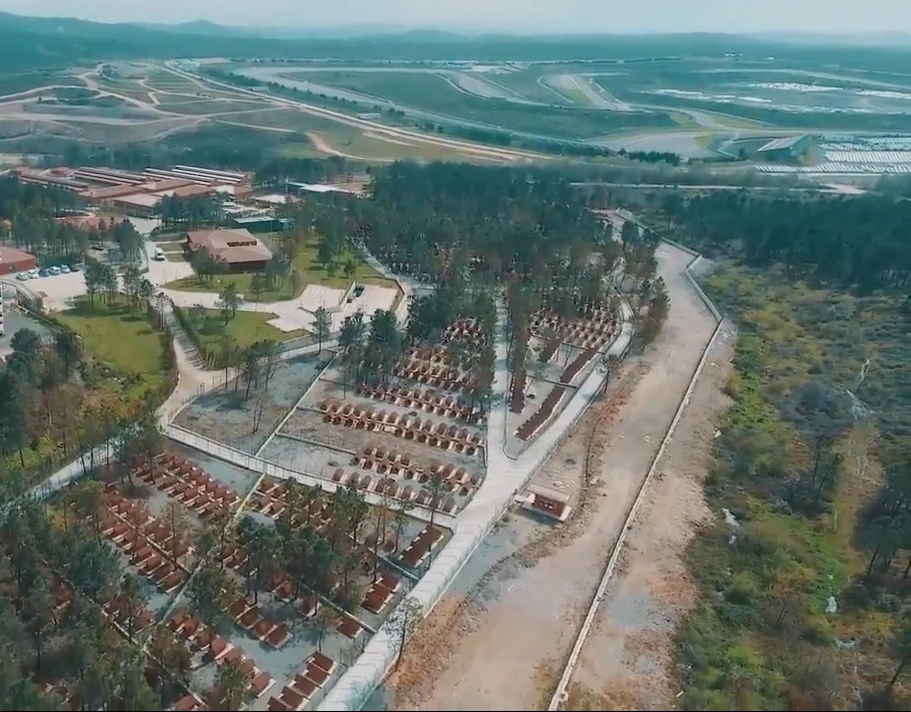

İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality Kısırkaya Stray Animal Care Center, aerial view, 2017, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Life under confinement, Kısırkaya Stray Animal Care Center, 2021, photograph Mine Yıldırım

İstanbul Metropolitan Municipality Tepeören Stray Animal Care Center, 2019, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Despite this legal recognition of street dogs' local embeddedness, municipal authorities' administrative reach continued to expand. The establishment of new veterinary affairs departments granted local governments greater authority to intervene in dogs’ bodies, lives, and environments. By the late 2000s, it became increasingly clear that shelters were not spaces of protection but sites of confinement and exclusion. As Istanbul’s urban landscape underwent a rapid transformation – driven by mass infrastructure projects and the dominance of the construction industry – street animals became subjects of mass deportations once again. In 2013, then-Mayor Kadir Topbaş declared the city had developed a ‘final solution’ to Istanbul’s street dog problem, unveiling plans to build two massive shelters on opposite sides of the city. The Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality (IMM) moved forward with the construction of two unprecedented facilities: one in Kısırkaya (Sarıyer) on the European side and one in Tepeören (Pendik) on the Asian side. Each was designed to confine tens of thousands of dogs at once. This time, isolation was no longer localized – it was a systematic, citywide operation.

Dogs exiled and abandoned near Tepeören Street Animal Shelter, 2018, photograph Mine Yıldırım

However, a new reality soon emerged that continues to define the present-day dynamics of care and violence toward dogs: Only a fraction of the dogs captured by municipal teams were confined within these massive shelters. The majority were instead abandoned in the surrounding peripheries, left to fend for themselves in inhospitable terrain far from the public eye.

Dogs abandoned along Northern Marmara Motorway, Section 4, 2017, photograph Mine Yıldırım

Care | Rethinking the dogs of Istanbul: The Four-Legged City

As Istanbul expanded along its east-west axis, driven by infrastructure megaprojects that defied urban planning principles and environmental sustainability, its urban peripheries were profoundly transformed. Forests fragmented by highways, airports, and bridges, and increasingly impoverished rural neighborhoods became the new dumping grounds for street dogs forcibly removed from the city centre by municipal authorities.

Mass dog exiles were no longer limited to remote islands, nor was their isolation restricted to mass shelters. Instead, the epicenters of dog removal policies became construction sites, roadside wastelands, and degraded forestlands on the urban periphery. These sites – where thousands of dogs were abandoned and left to die each year – formed a new geography of exile and isolation, deeply entwined with Istanbul’s urban transformation.

In response to this systemic violence, the politics of care now focuses on identifying and tracking the movements of displaced dogs, advocating for their right to life within the broader context of economic, spatial, and political changes shaping the city.

The Four-Legged City, a civil society organization, works to uncover and preserve the histories of street dogs subjected to isolation, displacement, and extermination – from the 1910 Hayırsızada Incident to the present day. Their mission spans archival research, historical and political analysis, and on-the-ground advocacy and protection efforts. By tracing the footprints of street dogs, both in historical narratives and daily urban life, The Four-Legged City continues to challenge the mechanisms of exclusion and extermination, pushing for a future where street animals are no longer treated as disposable beings.

The Four-Legged City is a non-governmental organization that traces the increasingly faint footprints of street animals who have been isolated, exiled, and exterminated in urban spaces from the 1910 Hayırsızada Incident to the present day. It works not for their ‘good death’, but for their good life. The efforts of The Four-Legged City are shaped by the attempt to make visible the lives, illnesses, and deaths of dogs – their joy and their pain – in the city, on the street, in everyday life; by the effort to hold the hands that reach out to us from under the rubble, from the destruction and devastation, and to listen to their voices.

The organization searches the archives for their trembling but resilient legs, for their anxious, distrustful, yet always tender eyes. It strives to seek, find, acknowledge, and make visible and audible the dogs from within official narratives, memories, documents, and testimonies; from within the language of politics, the realms of art, literature, and representation; from the transformations of the city and daily life. It endeavors to create space for these animals – whose slaughter is once again being decreed today – and inspires others to do the same.

Street dogs are not merely victims or passive casualties of violence. Each one is unique, emotional, sentient, and a bearer of rights – erratic, unruly, and affectionate subjects. The organization advocates for the urgency of care in response to discourses and systems that distance dogs from public spaces, that restrict and surveil human-animal interaction and coexistence, that vilify through discrimination, and that discard some while gentrifying others under the label of ‘acceptable animals’, in line with capital and violence. It reminds us of the efforts to live and let live between human and canine residents of the city, of the responsibilities born out of mutual vulnerability, and of the possibilities of coexistence rooted in our shared fragilities. It works to bring forth humans’ ability to respond to each other’s call – human and animal alike – and to the needs and searches we share.

The Four-Legged City works for the lives of dogs – for their rights, for their close and peaceful relationships with humans, for their freedom, health, and natural movement – for lives wrapped in care, love, compassion, curiosity, and attention. Compassion for street dogs and care for animals are the only forces capable of overcoming the violence that surrounds their lives. Efforts to protect the most fragile among us are the greatest strength for living together.

Today, as the door of the law is once again slammed in the faces of dogs and other animals, The Four-Legged City whispers into their ears: ‘You are not alone; millions of hands reach out to you,’ and reminds us all that care for these dogs has always, always defeated violence – and it will, again.

Dogs abandoned along Northern Marmara Motorway, Section 5, 2017, photograph Mine Yıldırım

EPISODE V

Today: Before the Law

Collective, The Rescue of Firuze, 2024, photograph

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

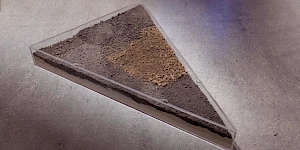

The Soils Project

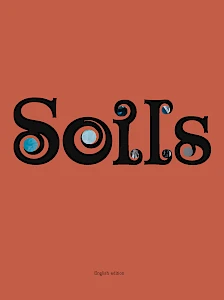

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

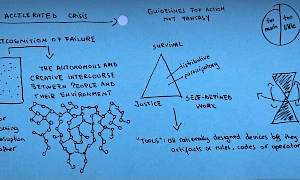

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

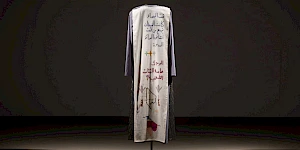

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

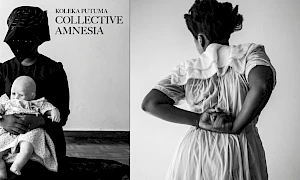

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations