The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

In her essay, curator and editor Rana Anani discusses the damaging effects of post Oslo Accords funding structures on Palestinian culture. Anani argues that the system has entrenched Western interests whilst weakening the resilience of Palestinian institutions and artistic communities. She further examines the decimation of Palestinian culture as a result of the ongoing genocide in Gaza. This essay was first published in the Institute for Palestine Studies, where Anani is a fellow.

The paper focuses on the role played by Western donor countries after the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in 1994 in weakening the resilience of Palestinian culture. This was done, the paper outlines, by flooding Palestine with funding, then withdrawing it progressively, and restricting it with conditions in an attempt to subject Palestinians to the culture of peace and the Oslo path, severed from the culture of resistance and resilience associated with the reality of Palestinians in the occupied territories. When Israel launched its genocidal war on Gaza, the role of Palestinian cultural institutions was weak, as was its resilience structure and programmes. Ambiguity still surrounds the role of Palestinian culture in the near future in light of the heavy losses it incurred in Gaza with the martyrdom of dozens of artistic and literary creators and the destruction of cultural and artistic centres, workshops and libraries on the one hand. And, on the other, the state of shock and paralysis that afflicted the cultural sector in the West Bank and the occupied territories, and the confusion and inability to transform reality into a platform for challenging, and ending the cultural siege imposed by Oslo.

Oslo and the Illusion of Culture

The return of the Palestine Liberation Organization to occupied Palestine following the Oslo Accords in 1993 and the establishment of the Palestinian Authority in 1994 opened a new chapter in the Palestinian struggle. The role played by small community and popular institutions, unions, and individuals in the occupied territories was reassigned to formal and informal institutions that were funded by the Palestinian Authority and donors. The Palestinian Authority pursued neoliberal policies that enhanced individuality over collective action, leading to the dissolution or weakening of trade unions and federations. The role played by the city of Jerusalem and other cities in 1948 occupied Palestine and their institutions in Palestinian culture also faded, as the centre of cultural gravity moved to Ramallah, the city that received the lion's share of foreign funding.

Oslo and the intervention of foreign funding contributed to curbing prevailing cultural life and undermining its organic development. It was amputated for the second time, following the first amputation after the Nakba. Culture became domesticated by foreign funding and was unable to carry out its critical role in taking a position in the face of the occupation. Rather, it merely made an attempt at survival (as opposed to resilience) by sustaining its activities within the limits and policies dictated by foreign organizations. It focused on topics un-related to the reality of the occupation and the existential threat to Palestine, and on spending funds to satisfy donors. Thus, cultural life has moved away from one of resilience and resistance, despite the apparent abundant production taking place. In this respect, Abdul-Rahim Al-Shaikh says: ‘The Palestine Liberation Organization succeeded in free falling into the post-colonial wheel when it turned into an “authority”, turning the page on “liberation”, without opening the “independence” page. Between the two pages, which were not validated by a proper conclusion, the Palestinian Authority built its state illusion in happy Ramallah...’. He adds: ‘The Palestinian civil society has turned, for the most part, from a participatory role in the national anti-colonial movement into a manicured structure, coexisting with the colonial reality, and seeking, at best, to “dismantle” (de-colonize) it through law, procedure, or architecture…’1

Meanwhile, the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement set off from Palestine to the world. The academic and cultural boycott campaign was launched, joined by artists and academics from all over the world. It pushed for the cancellation of cultural performances and events in the occupying state, and stood against cultural normalization through which Israel tried, with Western assistance, to clean up its image after Oslo.

After 2001, donors began to follow the example of the United States by putting conditions on aid, censoring terms used by cultural institutions in their publications, including the words “Nakba,” “colonialism,” “apartheid,” and “right of return,” and withholding funding for projects related to the promotion of the rights of Palestinian refugees to return, demanding that the geographical scope covered by institutions be narrowed to the territory occupied in 1967, and directing funding towards projects aimed at “conflict resolution” and “peace building”.2 The European Union also followed the United States' lead in imposing conditional funding on Palestinian institutions, which led to most cultural institutions rejecting European funding in 2020, while others were forced to accept their conditions.

In 2019, German positions wilted and became more extreme against the Palestinians. A decision was taken to criminalize dealing with the anti-Israel Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement in Germany. This led to accusations of anti-Semitism being made against those working in the field of culture that advocated for Palestinian rights, which silenced many voices.

Over the past two decades, foreign funding has gradually withdrawn from the cultural field, leading to the concentration of its funds in a few large, active institutions, which has caused the atrophy of many small cultural organisations and popular community initiatives.3 In this context, Tariq Dana says: ‘The largest and most influential segment of civil society continues to rely on international aid that is largely politically and ideologically conditional, imposing many restrictions on the work of civil society actors’. He added that the hegemony of this segment ‘has depoliticized social sectors and led to the emergence of a new elite alienated from its surroundings, squandering millions on useless projects’. Instead of Palestinian civil society being ‘an arena for resistance and mobilization against fragmentation, it has become part of the fragmentation itself.’. 4

October 2023 War

The genocidal war on Gaza that began on October 7, 2023, followed two years in which a large number of martyrs fell in the Jenin, Tulkarm and Nablus camps on an almost daily basis. The number of prisoners in occupation jails increased and the restrictions on them worsened. As for artistic and cultural institutions, they were busy holding archival exhibitions, organizing poetry readings, receiving and handing out prizes, singing the praises of folkloric cultural heritage and legacy, and wasting money producing expensive publications that ended up in garbage bins. Many institutions used the English language – the language of donors – to address their audiences. As for Gaza, it rarely had a share in the programmes of these institutions. It was given at best a marginal position, or their activities were overlooked entirely.

The conditions imposed by the European Union on Palestinian institutions before the war on Gaza were not sufficient. Merely two days after the declaration of war, the President of the European Commission, the largest supporter of the Palestinians, stressed the necessity of reconsidering financial aid to the Palestinians in light of the events of October 7, announcing the insertion of more contractual terms related to “countering incitement”, including with UNRWA, in case a decision was made to continue partnering with Palestinian institutions.5

A group of Palestinian NGOs, including cultural institutions, responded by stating that ‘the international financing system is a tool in the hands of colonial hegemony in our region, that the aid system is being used as a weapon to bring the Palestinians to their knees... and that this policy is an integral part of the Oslo doctrine and control systems imposed on us to maintain the security of the occupation’. They pointed out that the duty of organizations today is to ‘build a system of community solidarity and grassroots action networks, believe in the capabilities and potential of families and youth, remain alert to the hegemony of foreign funding, and deal with international institutions on the basis of full equality.’6 While these institutions announced their intention to disengage from foreign aid, in reality, very few of them took practical steps to do so.

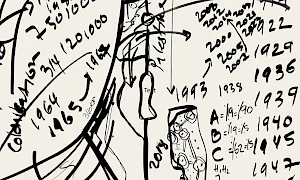

As the first months of the war successively unravelled, the Palestinian Ministry of Culture issued three reports on the losses in the Gaza Strip in the cultural field. The brutal Israeli bombing affected the lives of 41 artists, writers, musicians, poets and activists, men and women, in the field of culture,7 including the following artists: Mohammed Sami, Heba Zagout, Nismah Abu Shaira, Halima Al-Kahlot, and Mohammed Qraiqea, poets Refaat Alareer, Saleem Al-Naffar, Hiba Abu Nada, Mariam Hegazy and Nur Al-Din Hajjaj, journalist writers Mostafa Al-Sawaf and Abdullah Al-Akkad, photographer Marwan Tarzi, and guitarist Yousif Aldawas. Many also lost their entire families, and many more were seriously injured. Their homes, neighbourhoods, workshops, and productions were also destroyed. Cultural centres were completely demolished, including the Rashad Shawa Cultural Centre established in Gaza in 1985, and artistic institutions, such as Shababik Gallery and the Faculty of Arts at Al-Aqsa University. While some institutions were partially destroyed, such as Eltiqa Gallery, with all its artworks damaged, Al Sununu for Culture and Arts Association, which deals with music and included hundreds of musical instruments, and the Gaza Association for Culture and Arts, which was hosting the ‘Red Carpet Film Festival’, were destroyed. Public libraries were also destroyed, including Gaza Municipality's public library, which contains thousands of books, and Samir Mansour Bookshop, which contains thousands of titles – it was bombed in 2021 then rebuilt-, in addition to universities, archaeological sites, and archives. The house of artist Taysir Batniji was destroyed in the Shuja'iyya neighbourhood in Gaza City, and a large number of his family were martyred. He lost many works completed in an early period. Artist Fathi Ghaben lost his son, his house, his studio, and his works. As a result, his health deteriorated. Artists Mohammed Joha and Hazem Harb also lost members of their families. We saw artist Basel El-Maqosui on social media trying to hide his artwork by wrapping it in blankets and placing it under a table before his displacement. As for artist Maysara Baroud, not only did he lose his home, but also his studio and all of his artwork. The account of the fate of artists, writers, and cultural workers is still incomplete in light of continuing destruction and the scarcity of information.

As a direct result of the war, some institutions sought to document and stimulate debate on a number of topics. The Institute for Palestine Studies issued a Special Issue (No. 137) of Majallat al-Dirasat al-Filastiniyya under the title Salute to Gaza with the participation of 60 writers ‘as a historical document and collective testimony to Palestine's major event’. Its online platform was active in publishing through the Filistin Almaydan blog, with a large number of penholders, including direct testimonies from Gaza, in addition to discussion panels, videos, and policy papers. Fasha Taqafiya magazine was also active in publishing, organizing discussion panels, and producing “podcast” episodes, despite the restrictions imposed on the Palestinian territory. Birzeit University held a group of weekly seminars to shed light on different aspects of the war.

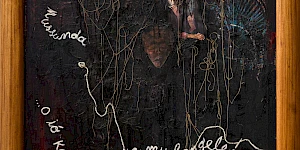

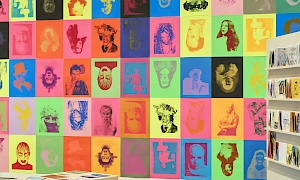

One of the most prominent events organized at this time is This Is Not An Exhibition at the Palestinian Museum in Birzeit, which brought together a large collection of works by artists from Gaza held by collectors in Ramallah, Jerusalem, and other Palestinian cities, in addition to the Missing People exhibition by Gazan artist Tayseer Barakat. The Palestinian Ministry of Culture has documented the damage to the culture sector in Gaza in three reports issued since the beginning of the war, in addition to a book of testimonies from Gaza, entitled: ‘Writing Behind the Lines’.

As for the voice of the occupied Palestinian territory, it has been suppressed since the beginning of the war. No demonstrations or protests were observed as was the case in the Uprising of Dignity events in 2021. Since the beginning of the war, the Israeli occupation authorities have arrested a number of figures and cultural symbols who dared to stand publicly against the war on Gaza on social media, such as artist Dalal Abu Amneh, actress Maisa Abd Elhadi, and other activists and influencers, in an attempt to silence the crowds. Palestinian students in Israeli universities were also subjected to physical and verbal threats and persecution. Israeli higher education institutions announced that they would not tolerate any publications that incite “terrorism”. Education Minister Yoav Kisch called for disciplinary measures against violating students.8 Organized campaigns were launched against university professors, as in the case of Professor Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian. Despite the repressive practices against journalists, a group of cultural media outlets at home continued to cover the war on Gaza, and a series of activities were organized, while being careful not to mention Gaza directly, in addition to a conference attended by 18 researchers, poets, and writers, which was held in Haifa in mid-December 2023, in cooperation between Mada Al-Carmel and the Arab Culture Association in Haifa.9

The Israeli aggression revealed the racism of Western cultural and artistic institutions and, for the most part, their subservience to the desires of politicians and donors. At the same time, groups of artists and cultural actors in the world mobilised in an unprecedented way to support Gaza and put pressure on Western artistic and cultural institutions, including the Decolonize This Place group in the United States, which organized protests in museums and art institutions that remained silent throughout the war, including demonstrations at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Hundreds of demonstrators participated. They demanded that the institution break its silence and expel board members involved in supporting the genocidal war in Gaza. The Strike Germany group also contributed to launching a campaign in the Western cultural community, calling for a boycott of German cultural institutions, specifically for their biased positions towards Israel, and for a change in their positions before re-engaging with them. A series of cultural activities in solidarity with Palestine were also held in various places, most notably an art exhibition organized by activists in the municipality of Barcelona in Spain, with Palestinian participation. A large number of artists signed a petition denouncing the barbaric Israeli aggression on Gaza and demanding a ceasefire. A number of celebrities from Hollywood also stood against the Israeli war on Gaza through public demonstrations and solidarity action, including Susan Sarandon, Cynthia Nixon and others, something that Hollywood actors would not have dared to do in the past for fear of the Zionist lobby.10

On the other hand, a number of Palestinian artists were subjected to international exclusion. The participation of artist Emily Jacir in a workshop at a university in Berlin was cancelled, a lecture by artist Jumana Manna at the Wexner Museum in Ohio was called off, and the retrospective exhibition of artist Samia Halaby at the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University in the United States of America was cancelled following three years of preparation. Many artists and cultural actors in the world were excluded because of their opinions on social media, including international Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, whose exhibition at Lisson Gallery in London was cancelled after lengthy preparations and shortly before the opening. Likewise, the tenth edition of Biennale für aktuelle Fotografiee was called off in Germany over the pro-Palestinian stances of its curator. Wanda Nanibush, an indigenous curator in Canada, was fired from the Art Gallery of Ontario for her activity on social media due to pressure from the Israel Museums and Arts – Canada. The Whitney Museum of American Art aroused the ire of American student groups that signed a petition against the Israeli aggression on Gaza, when American billionaire Ken Griffin, one of the museum's major backers, said that pro-Palestinian students should be blacklisted by their universities. An angry student march then headed toward the museum and flooded its entrance with red paint. The editor of the well-known art magazine Artforum, David Velasco, was fired after he published a statement of solidarity with the Palestinians, signed by a large number of artists, in which they called for a ceasefire in Gaza. The next day, the magazine published a letter condemning the “unbalanced” statement it published. Behind the scenes, the wealthy American art collector Martin Eisenberg put pressure on some of the artists who signed and whose works he owned, leading them to withdraw their signatures from the statement.11

Palestinians in the Area of Culture

Edward Said spoke of ‘the intellectual having to remain faithful to the right standards of human misery and persecution, despite their party affiliation, national background, and innate loyalties’, and said that ‘nothing distorts the public performance of an intellectual more than changing opinions depending on circumstances, observing cautious silence, and patriotic swagger…’12 But the genocidal war on Gaza revealed the fragility of the cultural structure in Palestine, its weakness, how its existence is dependent on foreign funding and partisan biases, its distance from its community, its fragmentation and loss of compass, specifically with regard to collective work towards a national liberation project. While many intellectuals remained silent and went into hiding, institutions suspended most of their programmes without offering an alternative that kept pace with the events and instilled a spirit of resilience in their audiences, without seeking to network with global solidarity movements.

The reaction of the Palestinian cultural scene, with its official and unofficial activities and institutions, in the midst of this unexpected and unprecedented attack, was extremely weak. A shock was felt, and the cultural field was paralyzed, revealing a lack of vision. Its main message was to prolong its life under the same Oslo conditions that led to this perdition. While art students at the Bezalel Academy of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, for example, engaged in sewing and weaving belts for the occupation soldiers who were exterminating the people of Gaza, the Palestinian students in the same college stood blinded, in a state of loss. They were not supported by a Palestinian university, for example, and there was no project to guide their efforts towards a specific goal.

In conclusion, it must be said that the duty of any Palestinian intellectual, today more than ever, is to put aside their party affiliations and narrow interests, to look to the future, and find their role and stance. This statement applies even more to Palestinian cultural institutions and levers of an official, semi-official, and popular nature. The time has come to unify efforts and respond to the existential threat through a clear vision and practical steps that serve as the nucleus for a “new type of resurrection.” The days of the Oslo illusion are politically and culturally over. This is a new and decisive phase that requires a unified front. The question is simply: to be or not to be.

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

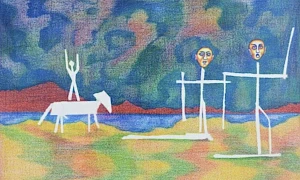

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

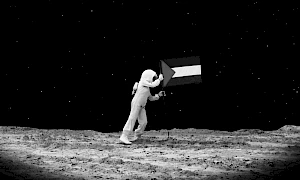

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

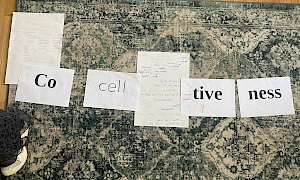

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

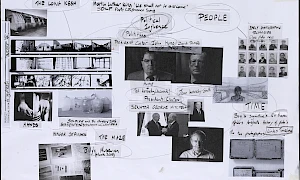

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

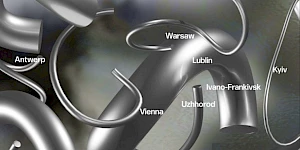

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma NaderEN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana IssaInternationalisms -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations -

Translated into Socialism: An experiment in internationalism

Merve Elveren, Tevfik Rada, Sezgin BoynikInternationalisms