Breaths of Knowledges

Robel Temesgen describes his ongoing artistic research project Practising Water; Rituals and Engagements, presented as part of Climate Forum IV 'Our world lives when their world ceases to exist'. Across two geographies – the Blue Nile in Ethiopia and the Glomma river in Norway – Temesgen’s investigation in and through water is articulated as a process of listening, breathing and translating.

Breaths of Knowledges: Practising Water

The invitation to breathe together is, perhaps, the most fitting entry point into a conversation about Practising Water.1 It began, as in the lecture that seeded this text, with an exercise borrowed from Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (2020).2 The collective act of breathing – listening to one’s own breath while attending to the rhythm of others – becomes a metaphor for a politics of attunement. To breathe in unison is not merely to synchronize lungs but to share vulnerability: to recognize that the capacity to breathe, both literally and metaphorically, is unequally distributed. In Gumbs’s formulation, learning to ‘breathe underwater’ becomes a radical pedagogy of survival, a method for living in the suffocating conditions of the contemporary world.3

This opening gesture situates Practising Water in the same current of thought: one that conceives of artistic research as a practice of collective respiration, a series of attempts to attune, to listen and to co-exist with forces that exceed the human. Listening, in this context, is not a metaphorical act but a way of practising relational epistemology. It asks for an openness that allows knowledge to arrive through resonance rather than declaration. Breathing together, like listening to water, teaches that knowledge flows through presence, duration and return.

Practising Water: a framework of relation

Practising Water; Rituals and Engagements is an artistic research project that studies the chronicles of water spiritualities and the symbiotic relationships they devise as modes of communication and language. Rather than treating water as a resource, metaphor or subject, the project approaches it as a co-constitutive being – an entity that listens, remembers, resists and transforms, shaping those who engage with it in return.4

At the outset, the project was guided by several open questions: What does it mean to engage with water not as material but as a living relation? How might such questions be approached through artistic practice, gestures, and rituals? What epistemologies of practising water can help us untangle such questions? These questions were not meant to be solved. Rather, they were companions, shaping the project’s path and deepening it through every encounter.

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, sleeping performance, 2023. Photo Shimelis Tadesse

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, sleeping performance, 2023. Photo Shimelis Tadesse

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Frank Holtschlag

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Karin Nygård

The methodology of Practising Water centres on listening as an embodied ethical and spiritual act: listening here not as passive reception but as a form of relation – as an attunement to silences, memories, and the more-than-human presence of water. The project emerges from a localized context, beginning at Gish Abay, the source of the Blue Nile in Ethiopia, and extending toward Lake Tana; then on to other bodies of water: the Glomma river in Norway, and beyond. The two geographies of the Blue Nile and the Glomma mirror one another as sites of offering and listening. Each encounter with water carries its own temporality and ethics.

Between these places, the project articulates what I call epistemic gestures – acts through which knowing takes form materially, relationally and ethically. Sleeping beside a river, painting with holy water, entrusting parchment to a current – these gestures embody knowledge through care and attention. They reveal that research, when lived rather than observed, is not the accumulation of data but the cultivation of relation.5

Material ethics and opacity

From its inception, Practising Water has been an inquiry into the ethics of artistic research. Working across geographies, I have sought to position myself not as an authoritative voice but as a participant within a web of relations – between human, spirit and water. The task, then, is to engage without claiming, to translate without appropriating, to create without erasing the contexts from which meaning arises.

This ethical stance finds resonance in local epistemic traditions such as säm-inä-wärq (wax and gold), a poetic system that encodes double meanings within language, allowing the spoken and the concealed to coexist. Within Practising Water, this becomes a methodological analogue for opacity – a way of holding knowledge that invites interpretation without surrendering depth.6 To withhold is not to deny, but to care; to listen before speaking. Opacity becomes a relational ethic, one that acknowledges that some knowledges protect themselves through layers, and that what is concealed remains active.

Within the artworks in the project, opacity is also material. It resides in the parchment I use in my work, which absorbs moisture and resists fixity; in the painting pigments that blur rather than define; in the gestures that elude translation. These qualities shape not only what the work reveals but how it behaves over time – fading, shifting and returning with new forms of meaning. The ethics of opacity thus extend to the processes of making and sharing, allowing the work to remain open-ended, unpossessable and alive.

Painting as translation and holding back

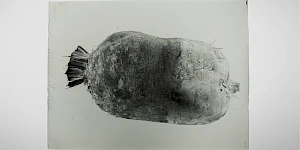

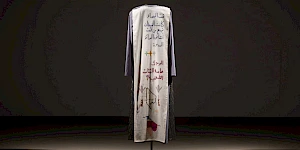

One of the project’s central articulations takes form in a monumental painting – 60 metres long and 4.5 metres high – composed of hundreds of pieces of goatskin parchment. The decision to use parchment was not aesthetic alone but ethical, an attempt to find a material capable of carrying the density of stories gathered over time.

The parchments were commissioned from local artisans, sustaining a lineage of craft that bridges generations. Each piece bore traces of touch, life and labour, forming a kind of collective skin. When sewn together, they created a continuous, breathing surface – a riverbed of memory.

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, sleeping erformance, 2023. Photo Shimelis Tadesse

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, painting performance, 2023. Photo Shimelis Tadesse

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, exhibition documentation, 2023. Photo Kunsthall Oslo

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, exhibition documentation, 2023. Photo Kunsthall Oslo

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Practising Water, exhibition documentation, 2023. Photo Kunsthall Oslo

On this surface, I painted with diluted pigments and graphite, tracing tools and gestures associated with rituals of water: vessels, cords, fragments, shadows of breath. Many of these shapes were drawn from stories collected in fieldwork, yet their translation remained deliberately partial. What was withheld became as significant as what was shown. The act of painting turned into an act of listening – listening to the material, to the stories that resisted depiction, to the silences between gestures.

In this sense, painting became an epistemic gesture: an embodied negotiation between what can be made visible and what must remain veiled. Holding back became both method and stance – an acknowledgment that relation requires distance, that meaning deepens in the space between.

Fieldwork, studio work and the ethics of rhythm

The project unfolded through two interdependent ‘spaces’: fieldwork and studio work. Fieldwork extended beyond ethnography – it was a practice of being present, of attending to water and its stories. At Gish Abay, I listened to those who live by the spring; to songs, to silences, to the tactile rhythm of water as it emerges from stone.

The studio, in turn, became a space of reflection and continuation. Fragments gathered from the field reappeared in material form – drawings, pigments, parchment – altered through time and distance. The studio was another riverbed, where what had been submerged resurfaced differently.

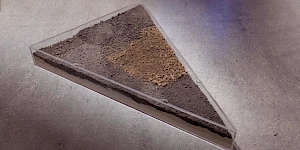

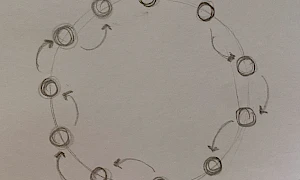

This cyclical movement between field and studio mirrors the hydrological cycle itself: evaporation, condensation, return. The project’s second geography, Norway, introduced another current. Near the Guttormsgaard Archive in Blaker, I began observing the Glomma river. The archive held Ethiopian manuscripts collected decades ago – traces of another crossing. This meeting of manuscript and water, of archive and river, became the ground for Meeting Glomma – New Waters (2024-2025).

In this work, a 78-metre parchment leporello extended from the archive to the riverbank. Participants followed it through snow, their breaths visible in the cold air. The parchment absorbed water, decayed and, five months later, was retrieved in fragments, discoloured and fragrant with river silt. The act echoed a story from Gish Abay, in which Abune Zar’a Brook entrusts prayer books to the spring and later finds them intact. Here, that gesture was reimagined as correspondence across waters: the Blue Nile and the Glomma conversing through time, through trust, and through matter. But unlike the books of Abune Zer’a Brook, I anticipated the leporello’s alteration as a sign of conversation rather than dictation.

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Frank Holtschlag

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Frank Holtschlag

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Frank Holtschlag

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Frank Holtschlag

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Karin Nygård

Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Meeting New Waters, Glomma River, performance documentation, 2024-2025. Photo Karin Nygård

Ritual, performance and the exhibition as a riverbed

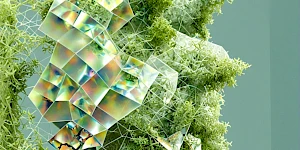

The project’s exhibitions have been less conclusions than continuations – spaces in which research breathes. The Eye of a Water (2025) installation transformed the gallery into a riverbed of parchment and pigment, an environment where visitors entered as bodies of water themselves, their movement through the space completing the relational circuit. 7

The exhibition offered no narrative closure; instead, it unfolded as a flow of submersion, texture and opacity. The audience was invited to listen with their bodies as waters – to sense knowledge as humidity, as resonance. The work’s abstraction was deliberate: it made room for the unknown. Within this atmosphere, opacity functioned as generosity – allowing each viewer to find their own rhythm of relation.

The exhibition thus operated not as representation but as a continuation of the research process – a performative space where material, ritual and thought converged.

All images: Robel Temesgen Bizuayehu, Eye of a Water, 2025 (details), Nitja Centre for Contemporary Art, Oslo. Photo - Tor S. Ulstein

Institutional gestures and relational ethics

Working within academic and exhibiting institutions, alongside communities and archives, required ongoing negotiation. The ethics guiding the artworks also guides the project’s relation to such infrastructures, each collaboration – with Nitja Centre for Contemporary Art, Guttormsgaard Archive, or local parchment makers – becoming part of a broader ecology of care. Financial and institutional exchanges have been treated as gestures rather than transactions; acts of commissioning parchment, producing manuscripts, or exhibiting works as moments of reciprocity. In this way, even institutional frameworks have become part of the project’s relational ethics: a recognition that every form of support carries history, value and responsibility.

These gestures – academic, material, collaborative – have coalesced into a practice of listening across systems. The project asks what it means to hold relation ethically in spaces of visibility, and how artistic research might offer continuity rather than extraction.

Breaths of knowledges

Practising Water can be understood as a series of iterative breaths. Each artwork, ritual and encounter is a respiration within a larger body – a pulse of knowledge that circulates between beings, materials and worlds. These breaths of knowledges are the living manifestations of the project’s epistemic gestures.

Each gesture – painting, offering, listening, holding back – breathes with its own rhythm, extending the project’s questions rather than resolving them. Together, they form an ecology of relation: water, field, studio, and institution all connected through cycles of trust, opacity, and care.

If the Blue Nile and the Glomma are two waters within this work, they are also two breaths – each carrying their own frequency, each teaching and revealing how knowledge moves between containment and release. Through them, I have learned that to practise water is to practise listening; to practise listening is to breathe.

And perhaps this is the most urgent lesson the project offers: that to know, ethically, is to remain porous – to breathe with others, to let understanding flow as water does, shaping and reshaping the conditions for living

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

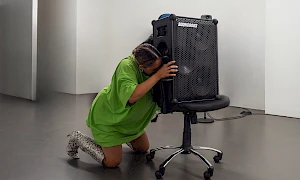

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

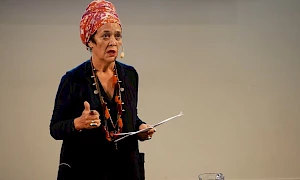

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

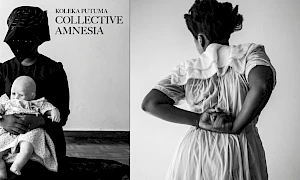

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations