Depression

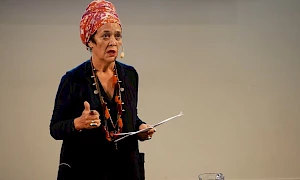

The following text is taken from Gargi Bhattacharyya's collection of essays We, the Heartbroken (Hajar Press, 2023). It was proposed by the artist G and curator Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide for their session ‘We the Heartbroken’, Part II as part of Climate Forum III. It is republished here with the kind permission of the author.

DEPRESSION

If any of the stages seems to seep into what we expect, or don't expect, from everyday life under late(r) capitalism, then depression is the one. So we know the signs only too well. Persistent low mood. Loss of enthusiasm and energy. Absence of enjoyment. Disrupted eating and sleep. Listlessness. Sometimes it seems as if it is only in the phase of depression that a person can get the performances demanded of the 'worker-citizen' about right. As you stare into space and stop going for lunch, expect your boss to remark on 'how well you are coping'. One of the tricky aspects of this stage is that the heartbroken may well be at their lowest but their behaviour appears more amenable to those around them. Depressed heartbreak is rarely disruptive or demanding or loudly eccentric. Depressed heartbreak is taking a step into death while looking like you have remembered how to behave. I think this tells us something about the half-deadness this world demands of us. Learning to go through the motions and not hope too much.

SALAD, OR A STORY ABOUT DEPRESSION

The story of Rapunzel begins because the mother cannot or will not eat. Nothing has passed her lips for too long, and her husband must watch her fade away before him, unable to rouse her to re-engage with life. It is this wilful falling into death that triggers the fateful trespass that makes the story commence.

What I remember is that the mother longs for the most delicious of salads. Hard for a child to understand, no? That the foodstuff you long for, the boundary between preferring to be dead and clinging on to life, could be green leaves?

In later life, the magical properties of the salad make more sense. In a reversal of the bargain that tricks Persephone into piecing out her freedom in morsels of fruit, the longing for a particular and elusive salad leaf is a marker of still being aligned with the world of the living. The mother hovers near to her death, almost gone, seemingly unwilling to help herself. She has entered a state where her love of life is losing to the allure of death. Only a memory of the taste of green leaves that sprout from the ground, a kind of metaphor for the life force of the earthly world, keeps her from falling back completely into the arms of oblivion. In the face of this, the woman's husband undertakes the most risky of trespasses. Entering the enclosed garden of the witch or the monster, stealing a handful of those delicious leaves. Of course, the story is that to steal back his beloved to the realm of life, the couple must relinquish their first-born. And so, Rapunzel becomes the name of one form of imprisoned femininity, the beautiful girl hidden away from the rest of the world.

As a child, I think I understood this as a story of betrayal. The father betrays the child by choosing the mother, often told as a matter of indulging his wife's whims. Perhaps the mother betrays the child by slipping back into life, back from the very brink, while sacrificing the child's future. But I wonder if it is really a story about moving beyond the stasis of depression, in the process accepting the terrible reality that your children will also live lives of sorrow.

Grief can feel like flying. Or falling. Or flying and falling, with

your body shooting out into a flurry of uncountable shreds,

ripping apart until there is no trace of what went before. It

can feel like disappearing, and the disappearance is a relief,

perhaps the first relief for so long, and then you are guilty at

the ebbing of pain and pinch yourself back into existence.

So, it starts again. Falling, flying, flailing. Lose yourself

and feel less, so feel less bad. Shake yourself back

into respectable pain.

Fall again.

And again.

And again.

Survive in this stage for long enough and you can begin

to feel like a superhero.

Perhaps we are learning to sit more easily with what Mary Oliver calls the soft animals of our bodies.1 I notice a greater tolerance of animalistic yearning. An acknowledgement in many places that this is also what we are, gravitating towards bodily comfort or release even as we try our best to keep the rituals of social propriety in play.

I have always been clumsy and uncomfortable in my body. Not only the overt attributes of gender but also just the meaty unwieldiness of an object that seems so far from my thoughts yet in which l have to live.

Grief split me still further from my coordination. I think this is quite common. Strange stigmata in the morning. Scrapes along my limbs. Scratches in places that no-one could reach. For a long time I found it hard to retain spatial awareness. How to walk down any space without bumping into the sides and the objects? How to place your feet without tripping over immediately? How to live in a world where it seemed at any moment the floor could come rushing up to your head? What your body needs and wants becomes so much more mysterious. Eating nothing or eating only one thing. Sometimes cramming your mouth full of sweets or chocolate or cheese or some other childish indulgence. Being given meals of kindness and chewing a few mouthfuls tastelessly. Washing more sporadically. Forgetting how to wash. I was definitely showering, but somehow the efficiency of my washing rolled right back to early childhood. Which bits do you do? How do you do the bits that are hard to reach? How do you know when you're done? How can you tell when you're dirty? And I know I looked dishevelled. Perhaps a trace of that dishevelled moment is still with me today. Maybe that too is part of the humanness of knowing grief in another. All of the hairs out of place, a slight dirtiness around the edges. Dishevelment can be part of how you show other people that you know there are more important things in life than this.

Perhaps the pandemic has reminded us all of our animal selves, returning us to soft flesh. Perhaps living through a pandemic has brought the experience of growing old into the lives of the young, pushing an awareness of mortality into places which should, in all fairness, be awash with hormone charged excess. Instead of feeling invincible, now everyone of all ages has been reminded, too insistently, of our shared frailty.

Animality is part of this. Something uncertain about species boundaries. Something about humans in an age of zoonotic disease. Something about the climate emergency. Something about our own bodies and their unpredictable eruptions and slowings-down.

I believed I stank of piss for a long time. I was not trying to be disgusting on purpose, although my ability to remember and complete the rituals of everyday cleanliness was impaired. For a while I thought this was another price of age. Survive long enough and your body will turn on you in these ways, puncturing any vanity you have left, making the smells and sounds and awkward shedding of aging apparent to all who come close.

(Now I think no-one around me was prepared for what giving birth twice in ten and a half months could do to a body in its forties. So, if this is happening to you or to someone you know, please seek help.)

No-one wants to become aware of the decay of their own body. But that too is part of understanding our limits and mortality. Grace in the face of frailty. But not only grace, with all its connotations of stoicism, but also a different courage. Not a flashbang demonstration of overcoming, or even a quiet battling alone. The part of feeling your own body's decay that counts, really counts, is the part where you find the soft animal. Because that is the part that might change what and how we are to each other.

I want to argue that an awareness of death is at the heart of all emancipatory politics and underpins all attempts at living an ethical life.

But even writing such a pompous phrase makes me pause to giggle. 'Living an ethical life: Frankly, as the old joke goes, what could make life feel more painfully endless? Being good might not make you live longer, but it will surely make the time pass more slowly.

Being bad, though-really hurtfully, sadistically bad, or bad in ways where you are barely aware of the damage you cause, or bad as an expression of your own deep hurts that you have no ways to address-being bad doesn't save you from loss, and neither does it render you immortal. Perhaps revelling in badness might promise the elation of knowing the gods are, if not dead, at the very least looking away. More often, I think, casual or insistent cruelty works to devalue everything that anyone could ever hold dear, because then the pain of loss is lessened.

Extending the realm of the sacred increases the danger of heartbreak. If every element of the world is enchanted, we feel the loss more keenly. If, on the other hand, the world and its inhabitants are spoiled through wilful neglect or violence or outright terror, then the sense of loss can be contained. Perhaps we even begin to believe that leaving this fallen world is a relief. When we dream of making the world better, we open ourselves to enchantment again. And the almost unbearable danger of enchantment is that the magic will end. The fairies will crumble to dust in our hand. The light will fade. The wonder will retreat, and we will be left bereft again.

Every doctrine of violence and machinery of reaction has relied on how frightening it is to contemplate the crushing of hope. Far safer to expel hope altogether. More sensible than the painful un-numbing of imagining other possibilities.

The other side rely on our resignation, and we are resigned to this fallen world because the scale of the loss would be unbearable if we were ever to acknowledge that each life, each moment, every one of us is a thing of enchantment. Because how, then, could we ever see the carnage and the cruelty and the wrecking of all that is beautiful and hold ourselves together at all?

The fear of even greater heartbreak keeps us in our place and keeps us divided from each other. What if you were really me and I was really you, if the boundaries between us dissolved until there was no longer any difference between my interests and yours? What if we are already as one and have only to see it?

And what if the elation and the ecstasy from this loss of self, which is also a finding of self, as each one of us delights in the coming home of being a part in the whole, what if a world made magical again can also be lost? Well, that really would be a loss, wouldn't it? A loss greater than we can imagine. Perhaps greater than we can bear, greater than anyone could bear, the drip-drip-drip of reaction whispers. How childish to think otherwise. What kinds of fools hope when the wise already know that hopes are made to be dashed?

Our fear of heartbreak is used against us so often and in such painfully ingenious ways.

So dreaming a new world requires a reckoning with heartbreak.

We, the heartbroken, must help each other to live with heartbreak and the fear of heartbreak. Otherwise, the risk of abandoning familiar pains for the unknown is too much for anyone.

It sounds like self-help, doesn't it?

However understandable the turn to self-care, let me say here that the mutual recognition and acceptance of heartbrokenness is not this. Much of the time, living with and helping others to live with heartbreak does not even make us feel better. It is certainly far from the varieties of distraction or wilful forgetting marketed as routes to feeling less bad. A reckoning with heartbreak requires something more and different from these desperate survival strategies.

Without making space for heartbreak, how can we remember why we long for change? But equally, when making space for heartbreak, how can we avoid being frozen by sorrow?

I don't think the ways of talking about emotional turbulence that arise as ways to function in the unhappy present can be enough for those of us trying to remake the world. I know we are also unwell. Often, all too often, self-medicating. Often trying to make lives in the debris of extreme trauma. Haunted by violence we have suffered or witnessed.

But I do think something shifts when we acknowledge our individual but interconnected heartbrokenness.

Unexpectedly, grieving people can laugh quite a lot. Sometimes they laugh in ways that embarrass others. Sometimes they laugh in a way that is mixed up with tears. A little bit frightening in a way we might have thought hysterical in another time. But there is certainly laughter. Sometimes wild, sometimes silly, sometimes just out of relief.

When we think of gallows humour, we tend to think of the transmutation of deadly contracts to more everyday drudgery. After all, none of us really faces the gallows on a day-to-day basis. What we do face is annoying, but less deadly. The slow drip-drip-dripping away of our life force. A disrespect for our time, time that is so clearly limited by mortality. An off-handedness that lets us know we are already as good as dead, so replaceable that our betters barely raise their heads to clock us before consigning us to an imagined grave and a younger, quicker, more compliant replacement. ln the face of all this, gallows humour is a way of reinserting our knowledge of death into the extreme irritations of the still living.

But I'm not sure any of that is really joking around about grief. Can people also laugh about their grief itself? Are there jokes to be told? Perhaps there are not outright jokes, with all the performance and scripting and expectation of some other as the audience, but there are all kinds of ridiculous and lighter moments as people move through grief. A kind of light-headedness where all the brakes are off. And although we still live in a world where people can be so, so painfully embarrassed by the grief-stricken, the grieving quite often ignore that and take advantage of their temporary status as living saints or crazed lunatics or wild-eyed harpies. Grieving is an excuse to park reason for a while, and when you park reason, all kinds of entertaining silliness can enter the room.

When I was a lot younger, someone told me a joke, partly inPunjabi (a language I do not speak). Broadly, it goes like this:

A family gathers around the deathbed of a beloved elder, letus say grandfather. Aware that there are only moments left, the grandfather asks of his bedside audience, 'Are you all here?'

'Yes, yes, we are all here, of course, of course:

'ls my brother here? Playmate and rival and companion throughout my life, holder of our family secrets?'

'Yes, of course, brother, I am here:

'ls my wife here? Mother of our children, holder of dreams, the girl who stole my heart and kept it as her own?'

'Yes, yes, I am here, my love. Please calm yourself and conserve your energy:

'ls my son here? Apple of my eye, tall and broad and strong, my hope for the future that can still be built?'

'Yes, father, of course, I am here by your side. You know you

can count on me:

'And my grandchildren, are they all here?'

'Yes, yes, yes,' comes the chorus. 'We are all here to show our

love for you:

'My cousins?'

'Of course:

'Our lifelong neighbour, whose children grew up alongside

our own?'

'Yes, yes, I am here:

'Really? You are all here? Every one of you?'

'Yes, yes, we are all here, here at your side.'

'Then who is looking after the shop?!'

Much later, an older friend laughs when I retell the story, knowing the ending already ... because this is also a famous Jewish joke.

ln either telling, it is a puncturing of grief and the pomposity that impending death can bring. Maybe it is a joke on the teller - 'ha ha, look what we are like!' But it is also a reminder of the mundane demands of living that continue despite death.

Whatever we are living through and dying from, someone somewhere will need to mind the shop.

Jokes about heartbreak can work like this, puncturing the enormity of grief with a reminder of the ordinary. Maybe the bills pile up and the phone goes unanswered, but everyone needs to buy toilet paper some time.

Everyone knows the sex lives of the grief-stricken can be erratic, compulsive, desperate.

Be careful with them, and try to forgive their awkward passes as they clutch at intimacy.

If you are living through grief with your lover, retreat to bed when you can, when and if you can both bear it. When you haven't been opening the curtains anyway, so why not? Perhaps no-one is exactly feeling 'sexy', but make space for any and all physical comfort. If possible, try to fuck your partner as if they are a stranger, so the raw wounds of intimacy can be avoided and everyone can manage a few minutes of post-coital sleep.

On the whole, I think lust gets a bad rap from 'The Left'. This isn't helped by the widespread and largely ignored sexual exploitation within many leftist organisations. But lust-the longing for sexual contact with another, often a particular other-has its place in the imagining of a new world and probably

always has.

Living with heartbrokenness might also include making space for our unruly and irrational longing for sexual contact, so often with the wrong people in the wrong place at the wrong time. Whatever we do to try to minimise harm from these eruptions, I doubt that we can eradicate the longing.

ln my long-past youth, some would talk of post-revolutionary sex with a kind of reverence. Then, in this utopian future, we will be perfectly satiated through forms of union that escape the instrumentalism and objectification of sex shaped by commodification. Sexual exploitation will disappear, as will assorted minor cruelties arising from reducing another to your object.

But I wonder about all of this.

Desire is a tricky and unpredictable thing, and its trippy discombobulation is not so easily banished. We, imperfect humans, like it. And whether or not we want it, we do not control its hold over us. There is something in its compulsion that, like grief, opens us up in ways that make our interdependence apparent.

So make space for desire, even when it feels out of control. Because that embarrassing vulnerability, so differently excruciating to romantic longing, is also part of the heartbrokenness that lets us catch a glimpse of each other and what we, one day, might be.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

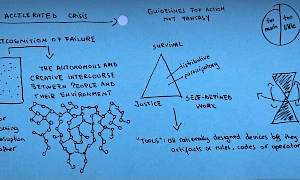

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

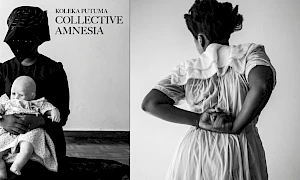

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations