Dispatch: A Silent Conversation

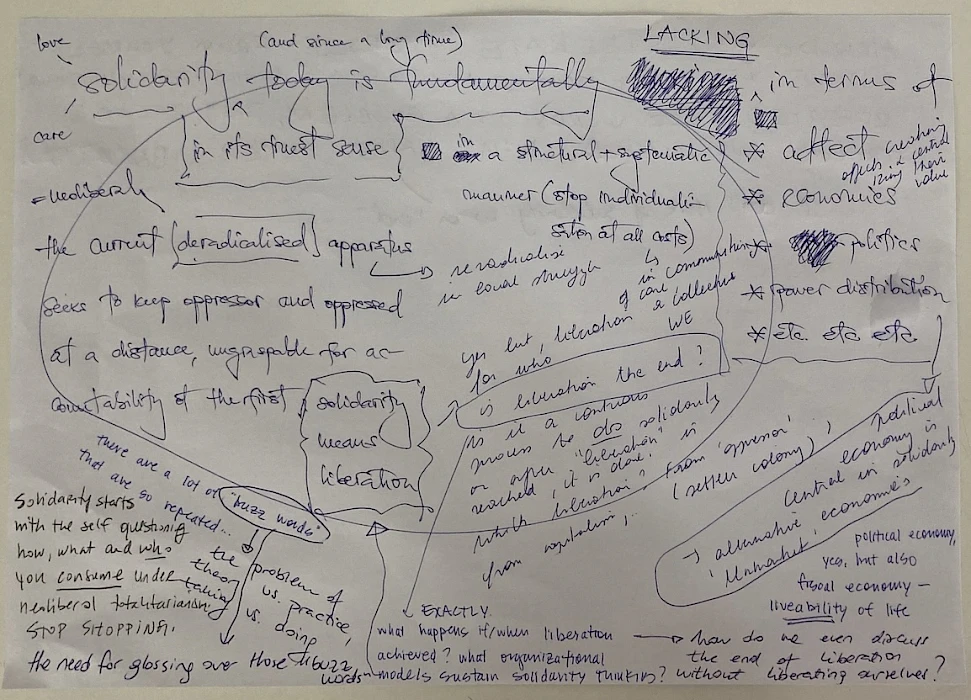

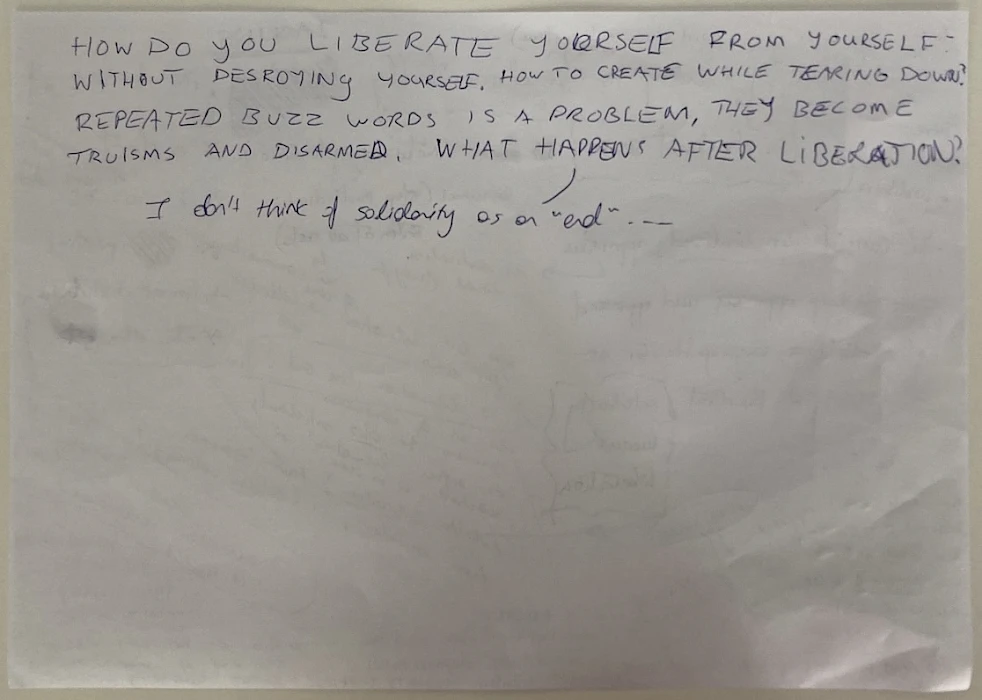

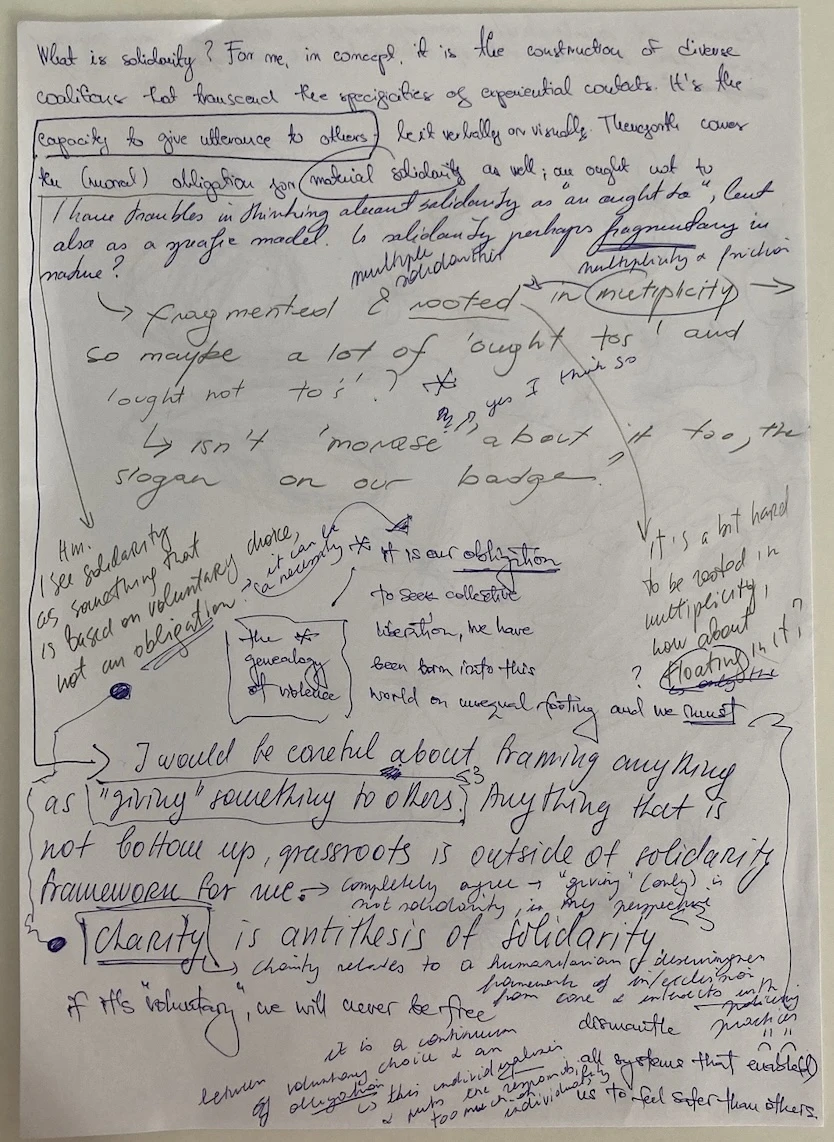

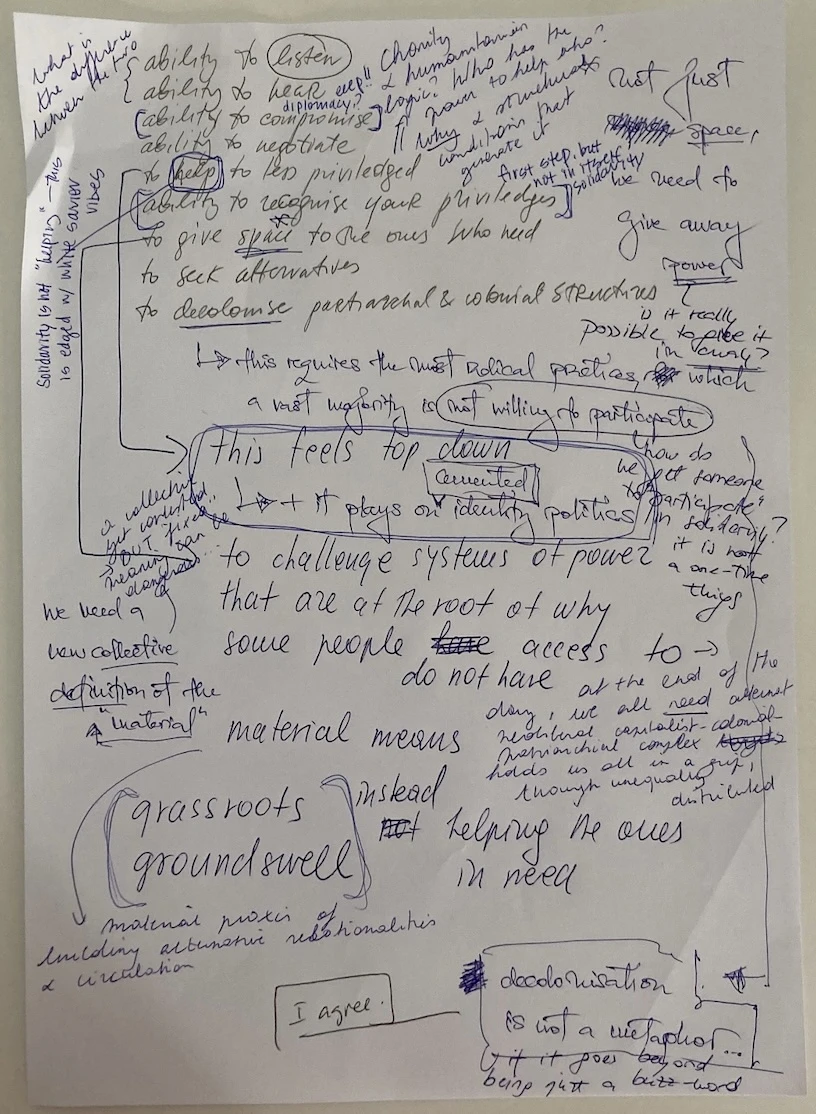

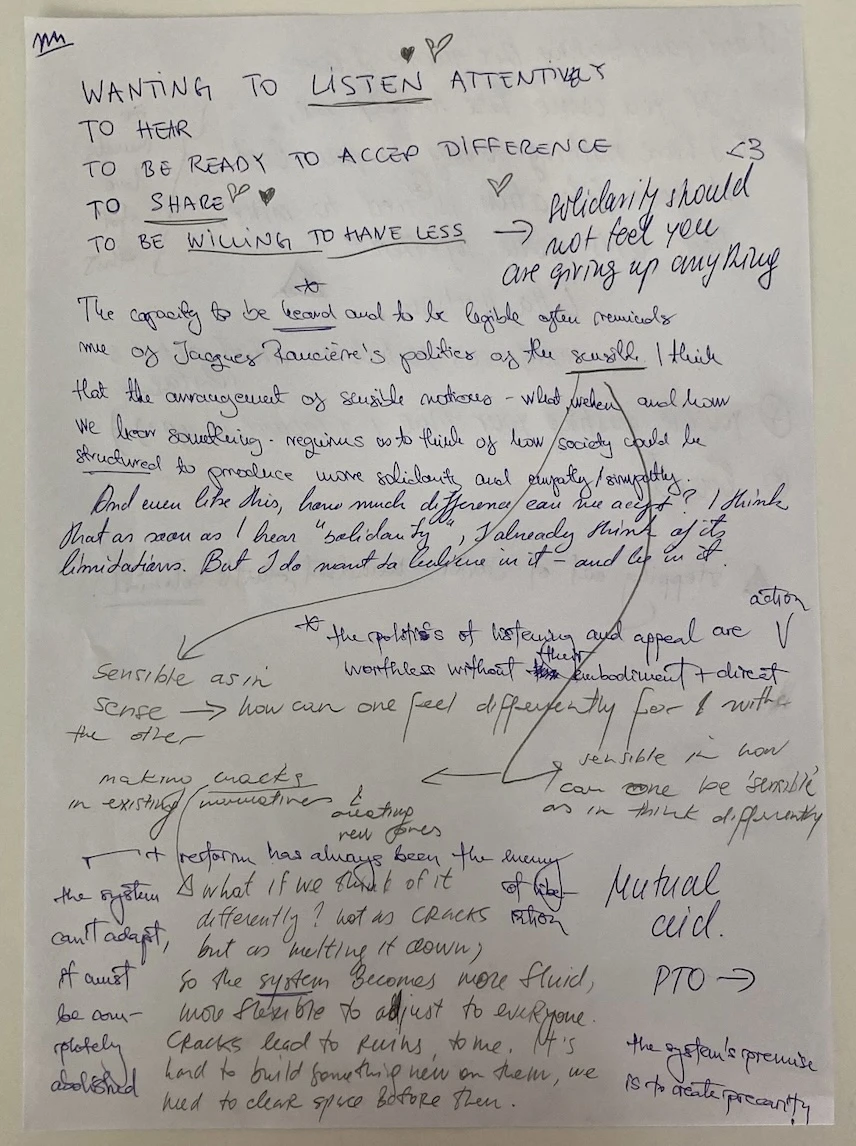

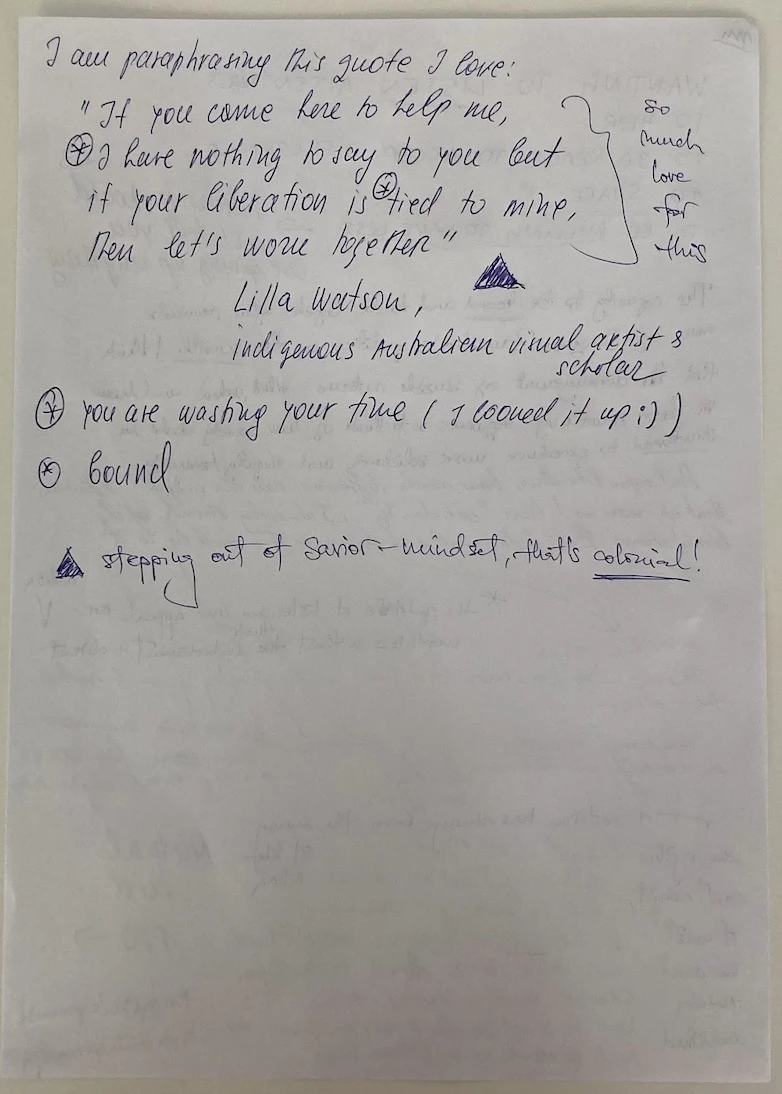

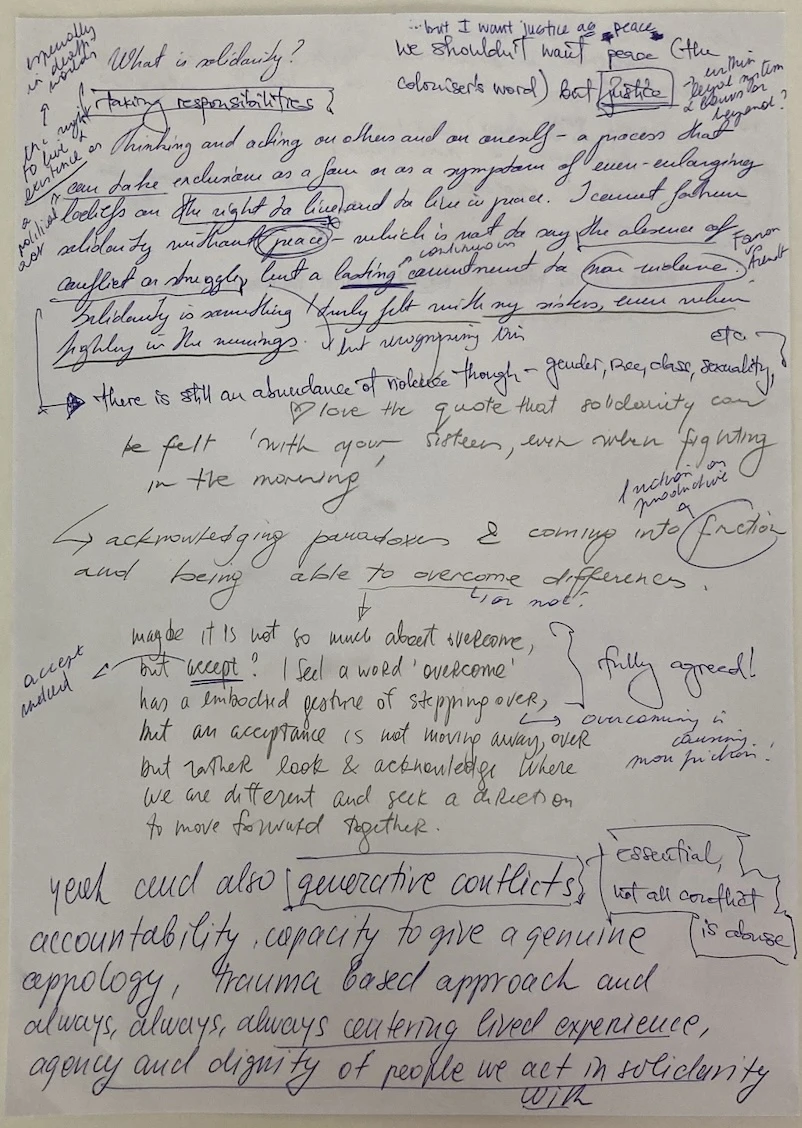

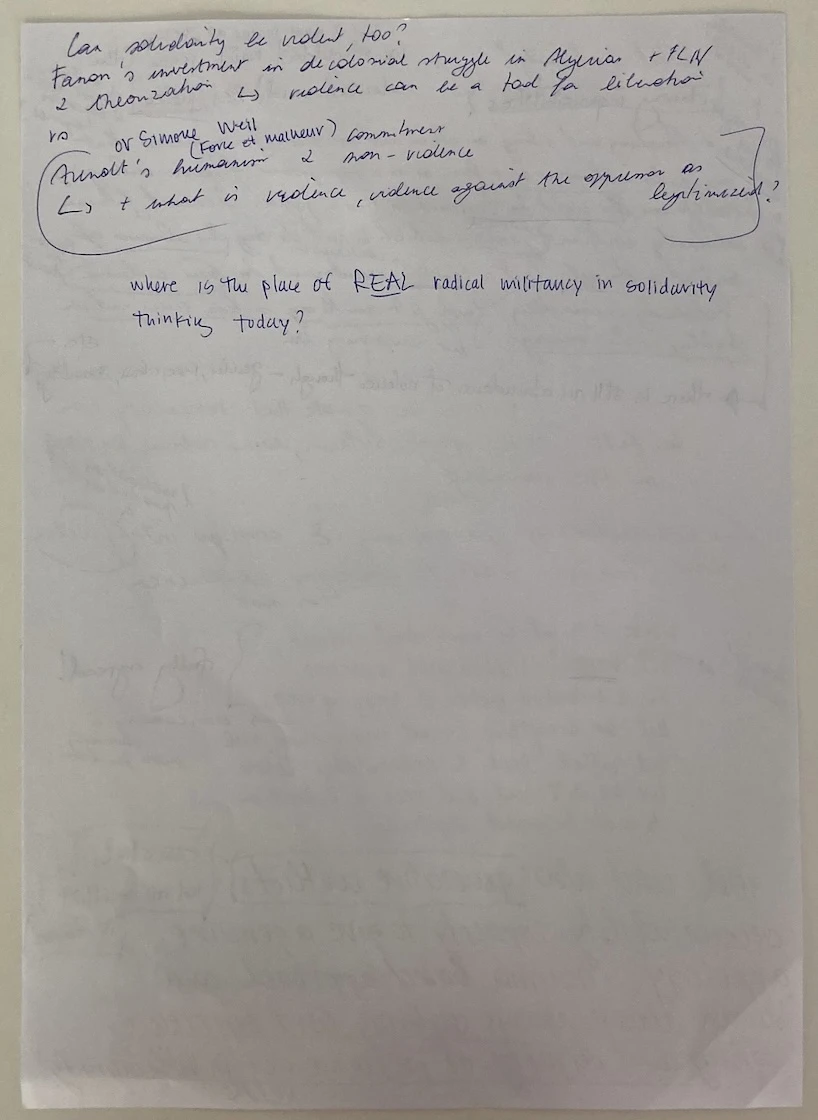

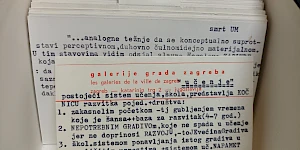

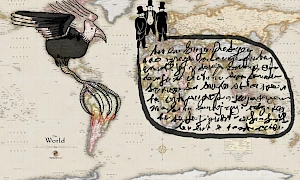

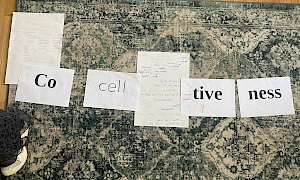

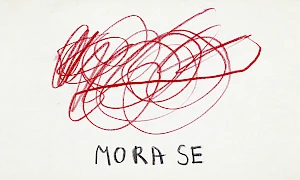

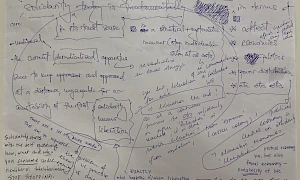

In her dispatch from the ‘Our Many Easts’ summer school, Anela Dumonjić reflects on what solidarity means for her. The contribution includes an introductory text and a series of notes taken during ‘a silent conversation’.

Solidarity is amongst the core mechanisms through which humankind has managed to persevere for millenia; the proof for this isn’t necessarily to be found solely in our ancestors, but in ourselves as well. Humans’ very existence is testimony to those who came before, their struggles, their resistance and their desires. And yet, despite it being profoundly embodied and constitutive of thinking subjects, there is no broadly agreed understanding of what it means, what it does and ultimately, how radical it is (supposed to be).

Today, holding space for multitudes feels vital. Post- and decolonial praxis have deconstructed singularity and arbitrary authority. The original (reliably) knowing subject, namely the ‘rational’ entity – always white, always male, always powerful – has, since the Enlightenment violently imposed its values on the world. Perpetuating the methodology of the oppressor will never create alternative, humane ecosystems of being, or, as Audre Lorde succinctly put it, the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. The notion of identity as something one has, instead of something one does, needs to be dismantled. Identities are processes, which are activated, fluid and contextual. This conceptualisation discards its fixed quality, undoing the idea that solely because one is oppressed on the account of one axis of identity, one cannot oppress others through other axes of recognition. All lives exist at the intersections of oppressions and privileges and all experiences are multidimensional. It mustn’t be forgotten that the need for historical accountability and responsibility is nothing less than ever-present, too.

Taking ontological complexity into consideration, how to deal/engage with the epistemic gap between subjects? Whom to learn from? Whom to learn with? Where is the willingness to unlearn and relearn situated? Is it intertwined with fear and punishment? Or is it embedded into the assemblage of love and care? What desires generate the knowledge people seek? What futures to struggle for? What affective developments take place during an encounter between subjects, whose premises and purposes don’t resonate?

The extent of what solidarity actually entails is as ambivalent as ever. The exercise of measuring its (potential? ultimate?) radicality needs to be problematised. However at the same time it is impossible to escape the all-encompassing neoliberal paradigm, with its sickening individualism and supremacy of comfort. The question of how radical should/could/must solidarity be has long been the target of critique, perhaps the aim wasn’t to defang resistance. Some slight relief can be found in the fact that the discursive register only matters so much, as the necropolitical apparatus continues to extend its brutality and dehumanisation.

Solidarity, to me, means only that which unfolds on the ground. To see another as vital for one’s own existence means to abolish all systems of power that prescribe different values to different lives. Although a system of binaries can often be catastrophic, solidarity is one of the very few spheres in which it makes sense – either one is committed to life, or one is committed to death. Even within this seemingly (for some ‘limited’) framework, there are countless ways of thinking and enacting solidarity. What is clear is that solidarity can never be selective, fragmented or disingenuous. All lifeforms are profoundly interconnected and dependent on each other. Humankind marks no exception to this, only in its extractivist disregard for other species, originating in colonial fantasies of unrooting the Human (the ‘rational’ subject, created to rule) from Nature (the ‘rest,’ created to be ruled). Or, to use the words of Maya Angelou, none of us are free until all of us are free.

Related activities

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Map of edible tensions

with Marina Monsonís, Paisanaje and Ruralitzem

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

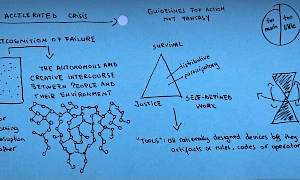

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MSU ZagrebVan AbbemuseumModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2024

MSU (Zagreb), Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven), MG+MSUM (Ljubljana), ZRC SAZU (Ljubljana) and L'Internationale invite applications for the new School of Common Knowledge (SCK) to be held in Zagreb and Ljubljana 24–29 May 2024. The School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. The SCK is built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna galerija (Ljubljana) and continues its co-learning methodology.

-

–MSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU

School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common Knowledge draws on the network, knowledge and experience of the L’Internationale museum confederation. Built on the basis laid by the Glossary of Common Knowledge, a project initiated by Zdenka Badovinac and Moderna Galerija in Ljubljana, it continues its co-learning methodology. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world.

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

–Museo Reina SofiaMACBA

Open Call – School of Common Knowledge 2025

Museo Reina Sofía and MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA) invite applications for the 2025 iteration of the School of Common Knowledge, which will take place in Madrid and Barcelona 11-16 November 2025. The School of Common Knowledge (SCK) draws on the network, knowledge and experience of L’Internationale. Its ambition is to be both nomadic and situated, looking at specific cultural and geopolitical situations while exploring their relations and interdependencies with the rest of the world. This year, the SCK program focuses on the contested and dynamic notions of rooting and uprooting in the framework of present – colonial, migrant, situated, and ecological – complexities. Building on the legacy of the Glossary of Common Knowledge and the current European program Museum of the Commons, the SCK invites participants to reflect on the power of language to shape our understanding of art and society through a co-learning methodology.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

Related contributions and publications

-

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Poner el nombre a una causa en tierra extraña

Dagmary Olívar Graterol, Paola de la Vega VelasteguiEN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Until Liberation I: Learning Palestine

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Omuz: A Solidarity Network

OMUZSALT -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

Glossary of Common Knowledge, Vol. 2

Schools -

Glossary of Common Knowledge

Schools -

Performances from the opening of The Heritage of 1989. Case Study: The Second Yugoslav Documents Exhibition

Jusuf Hadžifejzović, Azra Akšamija, Ilija ŠoškićDialoguesModerna galerija -

Epistemologies of the South

Zdenka Badovinac, Jesús Carrillo, Patrick FloresDialoguesModerna galerija -

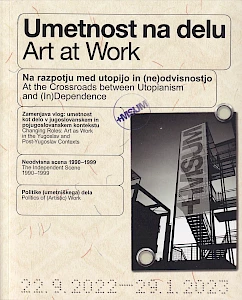

Art at Work – At the Crossroads between Utopianism and (In)Dependence

Moderna galerija -

Realize! Resist! React! – Performance and Politics in the 1990s in the Post-Yugoslav Context

Moderna galerija -

»We should never abandon the possibility of our active presence«

Zdenka Badovinac, Ieva Astahovska, Bermet Borubaeva, Darja Filippova, Nika Ham, Dorota Michalska, Radek Przedpełski, Ekaterina VorontsovaModerna galerija -

Our Movements Are Loud

Bridge RadioModerna galerijaHDK-Valand -

Tuning, Bias, and the Wild Beyond

Nora Akawi, Khyam AllamiModerna galerijaHDK-Valand -

Newsreel 65 – “We have too much things in heart…”

Moderna galerija -

The Heritage of 1989. Case Study: The Second Yugoslav Documents Exhibition

Moderna galerija -

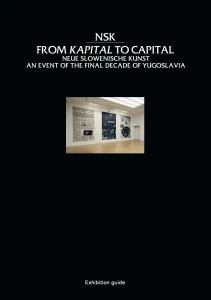

From Kapital to Capital. Neue Slowenische Kunst – an Event of the Final Decade of Yugoslavia

Moderna galerija -

Museums under Political Control

Workers from Moderna galerijaModerna galerija -

Towards Collective Learning, or, Decompartmentalizing Education

María Berríos, Fran MM Cabeza de Vaca, Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide, Nick AikensSchoolsSituated Organizations -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Reading list: School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common KnowledgeSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: In between the lessons. Staying together in uncertain times, laughing in the face of trouble, and disobeying; the future belongs to us

Antonela SoleničkiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: The Commonsverse and Situated Organisations – or why the era of big institutions will come to an end

Denise PolliniSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: A Buriti Tree

Lucas PrettiSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: To whom it may concern – the voice of the censor and re-calibrating words as an act of survival

AnonymousSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: A Silent Conversation

Anela DumonjićSchoolsModerna galerija -

Taking Part. A Guide to Participatory Tools and Techniques

EN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Atención: participar en el Museo de los Comunes

Fran MM Cabeza de VacaEN esSchoolsSituated Organizations -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape - bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD