Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Sonic Room is an auditory encounter with the ways in which animals communicate. It was a key component of the ‘The Lives of Animals’ exhibition at M HKA, Antwerp, in 2024, with a further iteration developed for Salt, Istanbul, in 2025. This online version has been created by curator Joanna Zielińska.

The Sonic Room is a crucial element within my long-term research into the complex and historically constructed relationships between humans and nonhuman animals. In the early stages of working on ‘The Lives of Animals’, I recognized the significant absence of animal voices and perspectives within the narrative framework of the project. Addressing this gap posed considerable challenges, as representing the standpoint of animals requires not only imaginative and ethical engagement but also an expanded notion of responsibility.

A significant influence on shaping this new research perspective was Temple Grandin and Catherine Johnson’s pioneering publication Animals in Translation: Using the Mysteries of Autism to Decode Animal Behavior (2005), which explores the profound connections between autism and animal cognition.1 Grandin, an expert in animal behaviour who herself is autistic, argues that her neurological differences give her unique insights into animal minds, behaviours and emotional lives. She emphasizes that animals primarily perceive the world through visual and sensory details. Unlike humans, who often overlook subtle visual cues, animals are extremely sensitive to even minor changes in their surroundings, such as shadows, colours or slight movements. These sensory details can significantly impact animal behaviour, leading to stress responses that humans typically misinterpret or ignore. Grandin highlights the importance of observing the environment from the animal’s perspective – literally positioning oneself at animal-eye level.

Contributors to the field of animal studies have long questioned the traditional anthropocentric belief that language defines the essence of humanity. In Animal Languages (2008), Eva Meijer draws from philosophy, linguistics and ethology to provide evidence that many animal species possess complex and meaningful communication systems.2 By combining empirical research with philosophical reflection, Meijer encourages a critical revision of the boundaries of language and the implications of interspecies communication. Animal languages often refer to sophisticated systems used by various species, frequently exhibiting remarkable creativity. The concept of ‘animal languages’ therefore encompasses communication systems demonstrating human language-like characteristics such as syntax, semantics and intentionality.

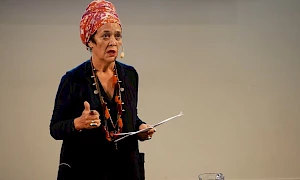

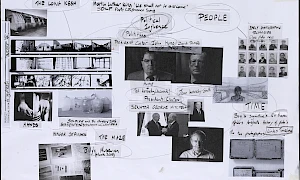

Installation image, The Lives of Animals, MuHKA, Antwerp. Photo: Kristien Daem

Recordings from the fields of zoomusicology and ecoacoustics presented in the Sonic Room partially fill the gap concerning animal cognition, even if, as humans, we do not fully understand animal communication and our imperfect ears are not adapted to receiving certain stimuli.

Birds, whales, primates and bats are renowned for their intricate vocalizations. Humpback whales create structured songs that differ geographically and evolve over time. Insects and mammals specializing in chemical communication use pheromones. Elephant trunk movements, primate facial expressions and bee dances are forms of body language. Dolphins use individual whistles resembling names, allowing mutual recognition within groups. Such systems support complex social interactions and group coordination.

Understanding animal languages and conducting ecoacoustic research can support the idea of rewilding and environmental conservation efforts, for example by analyzing how species communicate in fragmented habitats. Combining these studies with contemporary technologies can lead to a deeper understanding of the natural world.

Laughing rats, inaudible frequencies and humpback whale songs are just some of the sounds featured in the Sonic Room. In addition to field recordings, the programme also includes sound compositions created by artists and researchers in fields such as zoomusicology and ecoacoustics. Artists utilize field recordings to craft unique sonic compositions, while also critically engaging with the theme of multispecies communication.

A selection of sound works from Sonic Room at Salt:

Cevdet Erek, Barking Drums, 2010

Stray dogs have long been a part of Istanbul’s urban fabric, often cared for by locals. However, a 2024 law now requires their removal to shelters, with euthanasia for those deemed aggressive or ill. Critics, among them animal rights groups, have criticized this precautionary approach as inhumane, advocating instead for sterilization and vaccination programmes. Dogs take centre stage in the Istanbul edition of ‘The Lives of Animals’, the intertwined history of animals and humans creating a complex sociopolitical portrait that reflects broader dynamics within Turkish society.

The programme opens with recordings of barking dogs, captured by Turkish artist Cevdet Erek and transformed into a musical composition. Titled Barking Drums, the sound piece was originally created in 2010 as a 24-minute, eight-channel installation at La Gaîté Lyrique, Paris. It combines drum recordings played and programmed by Erek with the barking of dogs in Istanbul’s Maslak district. With his longtime collaborator sound engineer Murat Gülbay, Erek performed and recorded the percussion at Maslak 1024, located at the Maslak Atatürk Industrial Site where the stray and guard dog sounds were captured. The piece explores the rhythmic and sonic interplay between human percussion and canine vocalizations, reflecting Erek’s ongoing interest in blending carefully selected environmental sounds with primitive musical elements from everyday life.

Nathan Gray, Critical Flicker Frequencies, 2019

I’ve been following Nathan Gray’s work for over a decade. Through his projects that fuse sonic art and linguistics, such as The Weirding Module (2018–), The Mouthfeel (2019–) and Rogue Syntax: Primer (2021–), I’ve expanded my perspective on language, especially in the context of multispecies communication. Gray explores the voice as both a sonic and conceptual medium, using experimental formats such as performative lectures, radio plays and innovative narrative strategies. By employing microphone technology and digital sound processing, Gray reveals perceptual and scientific phenomena in ways that are both surprising and humorous.

In neuroscience and psychology, the concept of critical flicker frequencies (CFF) is used to study visual perception, attention and brain processing speed. In animal studies, different animals have different CFFs, which can tell us a lot about how they perceive the world. Gray’s radiophonic piece Critical Flicker Frequencies guides the listener through various sound frequencies and altered perceptions of time. It invites brief immersions into the sensory worlds of different species, allowing little time to acclimate before shifting to the next. Each sonic space is tinged by the previous one, their differing speeds, logics and temporalities blending and bleeding into each other. When they return, they do so with uncanny shifts. In ths way, Gray explains why television makes no sense to dogs and how flies perceive the human voice.

Kathy High, Rat Laughter, 2009–

While exploring examples of animal communication, I was particularly fascinated by the idea of rat laughter – especially since rats are animals that people typically find frightening. In A Thousand Plateaus (1987), Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari refer to rats as nodes in a conceptual apparatus, their subjectivity not fixed but fluid, multiple and always becoming something else.3 For them, rats symbolize resistance, multiplicity and transformation.

Neuroscientist Dr Jaak Panksepp, known for studying the brain’s emotional systems, discovered unusual vocalizations by laboratory rats that, he suggested, might have ancestral connections to human laughter. While studying the behaviour of juvenile rats in the late 1990s, Panksepp and his team used specialized microphones to detect high-frequency ultrasonic vocalizations (around 50 kHz) that rats emitted during playful interactions such as chasing, wrestling and even when being tickled by humans. These chirps, inaudible to the human ear without technological assistance, were associated with positive emotions. Rats that ‘laughed’ more frequently were also more socially engaged and displayed signs of being more resilient to stress. Panksepp suggested that this form of vocalization – expressing joy and play – represents ancient emotional systems shared across species. His findings not only reshaped how scientists understand animal emotions but also had wider cultural and ethical impacts, influencing artists and researchers interested in animal sentience, cross-species empathy and the emotional lives of animals. The idea that rats could laugh brought new depth to ways of thinking about emotion, communication and connection beyond the human world.

The recordings of laughing rats in the Sonic Room programme originate from Dr. Jeffrey Burgdorf, a former student and later collaborator of Jaak Panksepp, and are preserved in the archive of Kathy High, an interdisciplinary artist and educator whose practice lies at the intersection of art, science and technology. Through collaboration with scientists, she explores living systems, animal sentience and the ethical dilemmas of biotechnology. Her ongoing project Rat Laughter involves recording the ultrasonic vocalizations of laboratory rats – high-frequency ‘chirps’ associated with a state of contentment – which she uses to create musical soundscapes. Developed at SymbioticA, a bio-art research lab at the University of West Australia, the project investigates the contagious nature of laughter, hypothesizing that playing back these recordings might elicit positive responses among the laboratory rats. As High admits, the process of recording laughter is not easy. It’s entirely possible that laboratory rats don’t laugh all that often.

Jana Winderen, The Noisiest Guys on the Planet, 2009

I was searching for unique field recordings related to the field of ecoacoustics. Having already gathered whale songs, bat echolocations and various bird vocalizations, I still felt that something unconventional was missing from my collection. It was then that artist Nathan Gray introduced me to recordings of shrimp sounds by Norwegian sound artist Jana Winderen, whose academic background spans mathematics, chemistry and fish ecology. Her practice focuses on sound environments and creatures that are difficult for humans to access, both physically and aurally – deep underwater, inside ice, or in frequency ranges inaudible to the human ear.

The audio piece The Noisiest Guys on the Planet was created from two years of underwater recordings. Winderen explored mysterious crackling sounds produced by decapods – ten-legged crustaceans such as crabs and shrimp – recorded off the coast of Norway. Although the snapping sounds of pistol shrimp are well-known, they don’t live that far north, raising questions about which creatures were responsible for these sounds. Consultations with marine biologists did not yield clear answers, highlighting how little we know about underwater soundscapes. Winderen’s work is a sonic investigation into the hidden, noisy world beneath the waves.

Apian, Shared Sensibilities, 2020

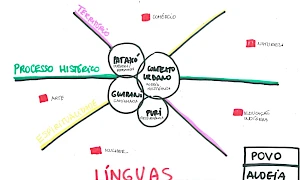

My conversation with Aladin Borioli in Amsterdam was one of the most interesting I’ve ever had about the animal world. We spoke about his research on Bannkörbe, a historical form of beehive, as well as about dreaming bees and the waggle dances performed by bees to inform other individuals about the location and quality of food sources. Borioli is the founder of the collaborative initiative Apian, also known as the Ministry of Bees. Combining anthropological and philosophical methods with practices of art and beekeeping, Apian explores the age-old interspecies relationship that humans have developed with bees. Through polymorphic ethnographies that merge photography, video, sound and text, it offers a space to encounter bees on more egalitarian terms.

The piece Shared Sensibilities is the result of a long interview with Dr Lars Chittka, during which we discussed the cognitive abilities of bees and how they perceive the world. Chittka is a renowned expert in sensory ecology and animal cognition. His lab explores bee behaviour, navigation and pollination through interdisciplinary methods, combining behavioural experiments, robotics and computational models to study how bees navigate complex environments. This work has reshaped our understanding of insects’ intelligence and their role in ecological networks.

The interview was edited and combined with music by Laurent Güdel and recordings made directly inside a beehive. The piece was co-commissioned by ICA, London, and the BBC, produced by SPACE, and first broadcast on BBC Radio in 2020.

Related activities

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

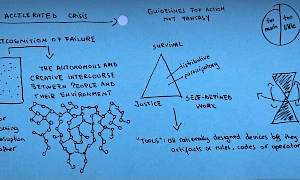

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

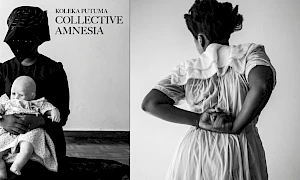

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations