The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

The following is an edited transcript of a panel that was held online as part of ‘Climate Forum II – Colonial Toxicity, the Climate Movement and Art Institutions’ on 27 September 2024. Convened by curator Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, the panel assembled research approaches and forms of address towards the ‘debt’ of settler colonialism. Each of the contributors spoke to, and from, former and present-day French colonies in the Sahara, the South Pacific and the Caribbean, and the various forms of ecological, emotional and imaginative damage that have been wrought there.

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez: I would like to welcome our four wonderful speakers, who have managed to join us despite the time zone challenges. I would also like to welcome listeners. I would like to thank Nick Aikens, Nkule Mabaso and L’Internationale Online (LIO) first and foremost. Working with LIO brings so many beautiful memories back, especially as the issue being addressed by this panel was the focus of the LIO e-book Ecologising Museums that we made nine years ago.1 While there have been many more discussions and conversations in museums since we put that publication together, what is lacking, I would say, is an intersectional approach. This conversation therefore aims to see how questions of environmental justice can be understood through an intersectional lens. Environmental justice is a systemic issue, a struggle against colonial capitalism that has been affecting the places from which we are speaking today for decades, sometimes centuries. There are a number of art institutions that, embracing the necessity for effective conversation about this issue, aim at going beyond the strategic symbolic gestures of greenwashing.

We will have contributions from Samia Henni, who is in Montreal; Olivier Marboeuf, who is sitting next to me here in Paris; Marie-Hélène Villierme in Tahiti; and Mililani Ganivet in London.

The title of this session is ‘Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe’. I am aware it sounds apocalyptic but we live in apocalyptic times, as the ongoing atrocities in Gaza, Sudan, Congo and elsewhere unfortunately attest. In July 2024, three months ago, Palestinian activist Susan Abulhawa remarked that, compared with the atomic bomb that the US dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, Gaza, which is 40 percent the size of Hiroshima, had had six to seven times more tonnes of bombs dropped on it since 7 October 2023.2 So, as of July 2024, 219 tonnes per square kilometre of Gaza versus 14.4 tonnes per square kilometre of 1945 Hiroshima.

What we are going to talk about today is the debt of colonial capitalist extraction. We will also focus on its naked impunity: What does impunity enable and what has it enabled in the past? I wanted to address this because it not only touches everyone who is listening today, but generations of our ancestors and generations of human beings and nonhuman beings to come. And the impunity with which colonial systems in particular have operated: when it came to extraction on the one hand as well as land appropriation and usage and the total abuse of that land on the other, all of this has been done with impunity. My understanding of this debt comes from the writing of our esteemed colleague Denise Ferreira da Silva, who has thought about the intrinsic links between coloniality and raciality, which she brings together with the term ‘unpayable debt’.3 This term addresses a debt you carry even though you are not the one responsible for something created over centuries of colonial abuse. Since we are speaking from the heart of empire in Paris, I wanted to bring the geographies of France’s colonial relations into dialogue: Algeria, Mā’ohi Nui or French-occupied Polynesia, which is still called French Polynesia today, and Guadeloupe, an island in the Caribbean which is also occupied by the French and where Olivier is from.

In our preparations for this talk we realized some people knew each other. Speaking from my heart, I am especially and sincerely indebted to Olivier and Samia for their very engaged, devoted and precise work and writings, and also to Marie-Hélène and Mililani, with whom I have had the chance to work at the Cité internationale des arts where we are sitting today. I now would like to pass the word to Samia.

Samia Henni: Thank you very much. I’m delighted to be here in this fantastic company. I think it’s important to have this conversation and to insist that colonialism is very much related to human-made climate change, the Anthropocene and the destruction of Earth. Today, I will share with you work I have been doing the last few years, a project called ‘Colonial Toxicity’ that discusses the continuity of coloniality that echoes the temporality of colonialism in many places around the world. Today I will focus on the French military nuclear programme in the Algerian Sahara that happened between 1960 and 1966. ‘Happened’, meaning that it technically happened between 1960 and 1966. But then it continued – because radioactivity does not stop when nuclear bombs cease to be detonated. Colonial radioactivity continued, continues and will continue for years – that’s also why it’s called ‘Colonial Toxicity’.

The French colonial regime, civil and military, built two nuclear sites in the Algerian Sahara: the Centre saharien d’expérimentations militaires (CSEM, or Saharan Centre for Military Experiments) in Reggane, on the Tanezrouft plain of the Algerian Sahara, approximately 1,150 kilometres south of Algiers, and another, the Centre d’expérimentations militaires des oasis (CEMO, or Oases Military Testing Centre) near In Ekker (also spelled In Ecker or In Eker), approximately 600 kilometres southeast of Reggane. When the French decided to test their nuclear weapons in Algeria, the country was under French colonial rule. The colonization of Algeria started in 1830 and ended in 1962; the War of Independence started in 1954 and ended in 1962. So the French nuclear bomb tests (1960–66) continued after independence. This is because the French promised the newly independent Algerian state that all nuclear testing would take place underground, inside a mountain called Tan Afella, and that therefore there would, as they believed, be no impact on the territory and the people of the Sahara. What happened was exactly the opposite. Out of thirteen underground nuclear bombs that were detonated inside Tan Afella, eleven were not contained. These ‘accidents’ had a huge impact on the area: environmental, social, political and economic.

In Reggane, between 1960 and 1961 four atmospheric nuclear bombs were detonated. Named after a small jumping desert rodent, an animal called gerboise in French, ‘jerboa’ in English, the four atmospheric bombs detonated in Reggane were named Gerboise bleue, blanche, rouge et verte (Blue, White, Red and Green Jerboa). And then, between 1961 and 1966, they moved their atmospheric nuclear bombs under the ground, into the granite massif of Taourirt Tan Afella. For their part, these underground bombs were named after gemstones, Agathe (Agate), Béryl (Beryl), Émeraude (Emerald), Améthyste (Amethyst), Rubis (Ruby), Opale (Opal), Topaze (Topaz), Turquoise (Turquoise), Saphir (Sapphire), Jade (Jade), Corindon (Corundum), Tourmaline (Tourmaline) and Grenat (Garnet), and detonated near In Ekker on the Hoggar mountain of Taourirt Tan Afella. In addition to these seventeen bombs, the French army also tested other nuclear technologies in the atmosphere of the Sahara between 1960 and 1966.

When I was working on the book Architecture of Counterrevolution: the French Army in Northern Algeria,4 I focused on northern Algeria because it became clear that the next research project would centre around the southern part of Algeria, the Sahara, especially following the French promise to declassify some of the remaining classified archives in 2020. However, in 2020 the French authorities closed some of the archives that were already declassified and did not, in fact, open the archives relating to the nuclear weapons programme in the Sahara. In fact, they closed what was already open to the public.

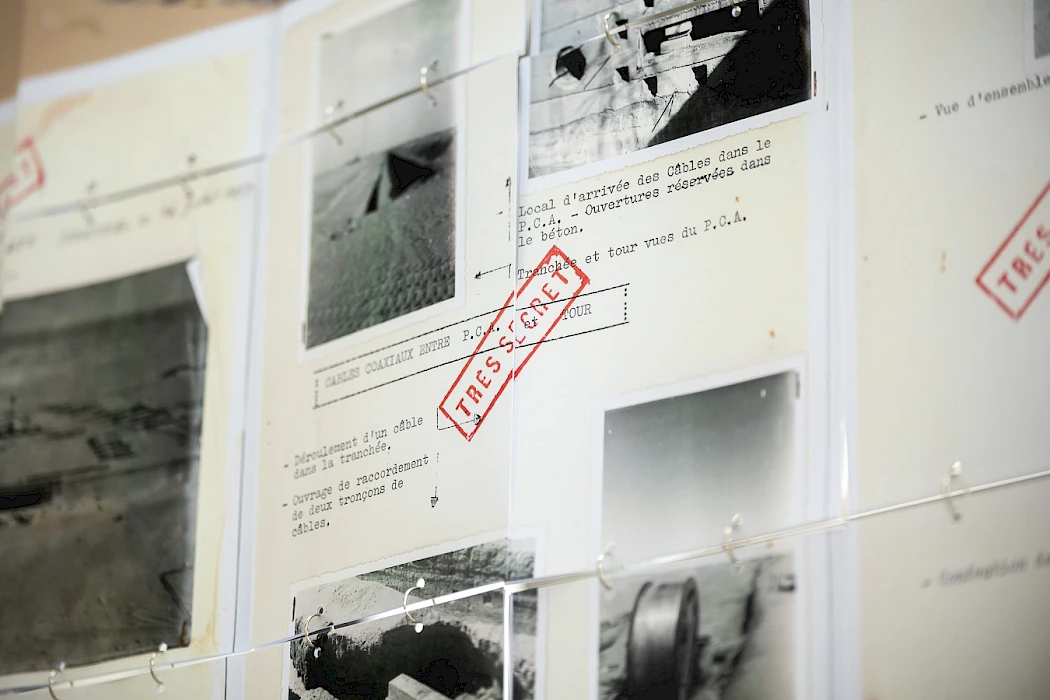

Photograph taken in the 1960s by French workers or officers who served in one of the two nuclear military bases (CSEM in Reggane or CEMO near In Ekker). The panel clearly forbids employees and passers-by to take photographs of the sites, indicating that this site was classified as secret on grounds of national defence. Image courtesy Observatoire des armements

This is a photograph from the 1960s of a sign stating that pictures of the French nuclear bombs testing sites in the Sahara were forbidden, at that time, because they were supposed to be secret. Today, the French military archives of their 1960s nuclear programme are still classified. So this whole research project of ‘Colonial Toxicity’ was, for me, a question of how to make those events, that catastrophe, more public or more accessible to the public: How to find other ways of exposing this secrecy, knowing that these nuclear bombs were no secret for those living in the Sahara, nor for the French who came back to France having lived among and participated in the detonation of those atomic bombs?

When Megan Hoetger, programme curator of the Amsterdam-based performance arts organization If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part of Your Revolution, invited me to participate in their 2022–23 biennial Edition IX called ‘Bodies and Technologies’, I mentioned that I was working on my ‘Colonial Toxicity’ research project and that I wanted to find different ways of sharing this knowledge with the public. Therefore I proposed to use the following three forms of performativity, which were also three different forms of publicness: translating, exhibiting and publishing.

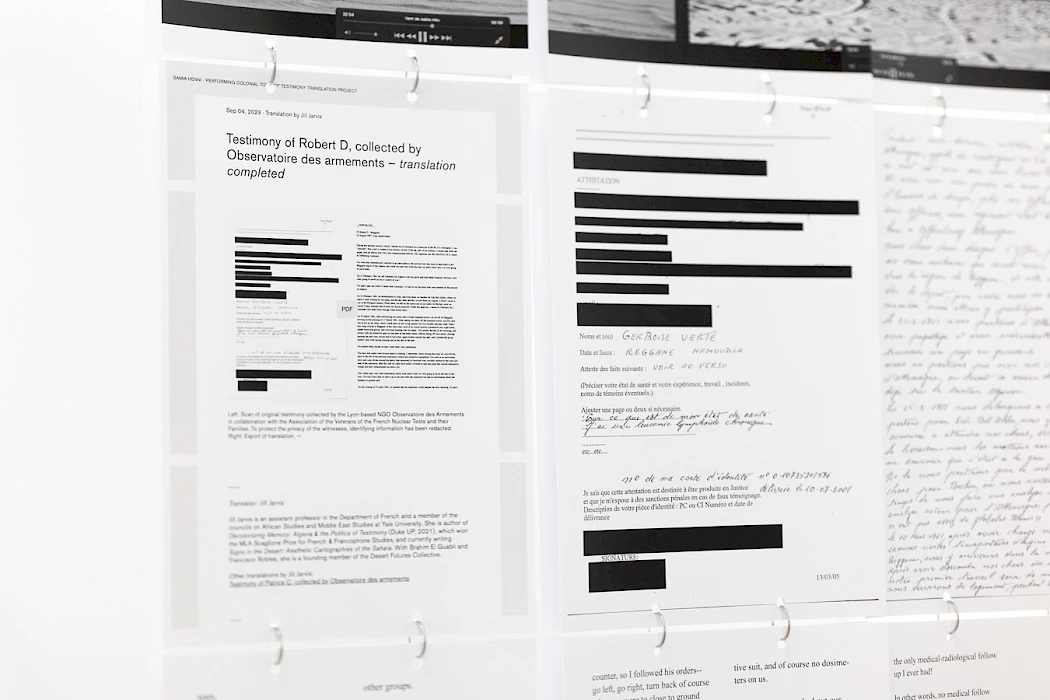

Of these, the translation act, called the ‘Testimony Translation Project’ (2023–), was and is indebted to the work of the French environmental activist Solange Fernex, the Lyon-based French NGO Observatoire des armements and the Franco-Algerian photographer Bruno Hadjih. They collected witness accounts from victims and survivors of the nuclear bombs in the Sahara, and who were either still in the Sahara or in France. I selected forty testimonies that were either in French, Arabic or Amazigh, and we invited twenty colleagues to translate them into English so that we could make them public and share them with the world. The twenty translator-participants include Raoul Audouin, Adel Ben Bella, Omar Berrada, Megan Brown, Séverine Chapelle, Simona Dvorák, Hanieh Fatouree, Alessandro Felicioli, Anik Fournier, Jill Jarvis, Augustin Jomier, Timothy Scott Johnson, Anna Kimmel, Corentin Lécine, Natasha Llorens, Miriam Matthiessen, Martine Neddam, M’hamed Oualdi, Roxanne Panchasi and Alice Rougeaux. We used the platform of If I Can’t Dance Studio to disseminate the original and translated testimonies. The publishing of these translations, which are still online, happened before the exhibition and publication to create awareness of the gravity and the seriousness of the disaster that this colonial toxicity generated in the Sahara and around the world.

The aim of the ‘Testimony Translation Project’ is threefold: first, to begin making these materials available for open digital access; second, to begin the long-term project of their digitalization, as well as their translation into English, allowing for searchability and broader transmission globally; third, to begin to build a broad network of ‘translator-participants’ – that is, of people who are not professional translators but instead come from various academic, artistic and activist spheres, with practices staked in French and/or Algerian history. This was and is the first disclosure of the ‘secret’ colonial toxicity which, I emphasize, is no secret to many victims and people. In fact, if one goes to Reggane or In Ekker, one will see open air archives of radioactive environments of ruins.

The second act was the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’ at Framer Framed in Amsterdam (October 2023 – January 2024). It was presented at gta exhibitions at ETH in Zürich (March – April 2024), and travelled to the Mosaic Rooms in London (March – June 2024). Thanks to the initiative of Ariella Aïsha Azoulay and Macarena Gomez-Barris, and the work of Adel Ben Bella and Amelle Zeroug, it’s going to open in two weeks at Brown University, and will continue to go to other places – Paris, Berlin, Ottawa and Montreal – next year. I’m mentioning these places because for me the exhibition is also a forum of research and of publicness, a way of sharing knowledge with different audiences in different places. This is also why I tried to design the exhibition in a way that means it can easily be transported around the world.

The show presents various available, offered, contraband and leaked documents in an immersive multimedia installation, creating with them a series of audio-visual assemblages that trace the spatial, atmospheric and geological impacts of France’s atomic bombs in the Sahara, as well as its colonial vocabularies and the (after)lives of its radioactive debris and nuclear waste. Architectural in scale, these assemblages, or ‘stations’, as I refer to them, were meant to be moved through and engaged with. Visitors were invited in to draw their own connections between what is present in the installation, as well as with what is absent from it.

Installation shots of the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’, 2023, by Samia Henni at Framer Framed, in collaboration with If I Can’t Dance, I Don’t Want To Be Part Of Your Revolution, Amsterdam. Photo © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

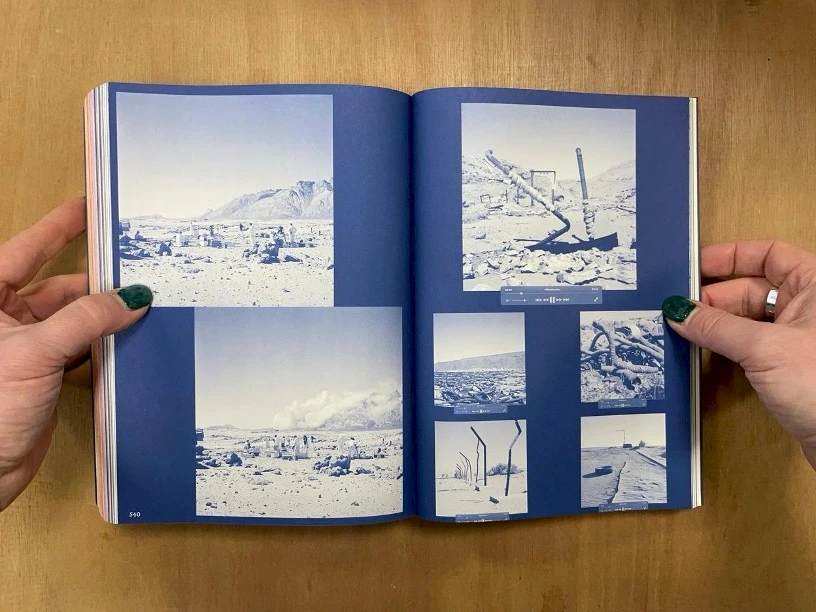

At Framer Framed, there were thirteen stations. Each station had a specific title, a descriptive text and an assemblage of images with their captions. For example, one station portrayed atmospheric bombs and one the question of justice. The translated testimonies of witnesses and victims were also part of the exhibition so visitors could read them in the exhibition, and there was a QR code that linked visitors to the online ‘Testimony Translation Project’. We also projected onto the stations the current environmental and spatial conditions in Reggane and In Ekker. In addition, we included a number of interviews with scholars, activists, photographers and people living in the Sahara so they could tell us about their version of the facts. The exhibition is a kind of juxtaposition of different documents, audio, photographs, maps, and stills from videos and documentaries. The idea is to create an assembly of evidence so that the public are surrounded by an undeniable amount of information. This is to oppose secrecy and to say that it is possible to find ways to gather and expose information. Even if some of the images were of low resolution, we were able to portray and illustrate the transformation of the territory, the destruction of the environment, and the denial of the past, present and future for the generations that live in the Sahara as well as the veterans that live in France.

Installation shots of the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’, 2023, by Samia Henni at Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Photo © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

As I mentioned, it was important to try to design this exhibition so that it could be easily deconstructed and reassembled – it’s very light and it can be reproduced very easily. This was of course a practical consideration, but it also challenges the temporality of colonial toxicity, meaning that historical and contemporary images and videos are exhibited on the same platform so that visitors can see that it is untrue that the French army dismantled the radioactive infrastructure when they left these sites and this territory in 1966, though they claim that after 1966, everything was cleaned or buried and that there is nothing to be seen there.

Installation shots of the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’, 2023, by Samia Henni at Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Photo © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

The exhibition also shows that most of those radioactive engines were buried under the ground of the Sahara, as you can see here in the station ‘Below Ground’. So this means that even the underground spaces and soils are also contaminated. I also used Google Earth to search for the coordinates of where the bombs were detonated and map the territory around them, and one can indeed see that there are many radioactive traces apparent in the contaminated territory today. Therefore the idea of the exhibition ‘Performing Colonial Toxicity’ was to make colonial toxicity, this invisible radioactivity, perform on the bodies and senses of visitors.

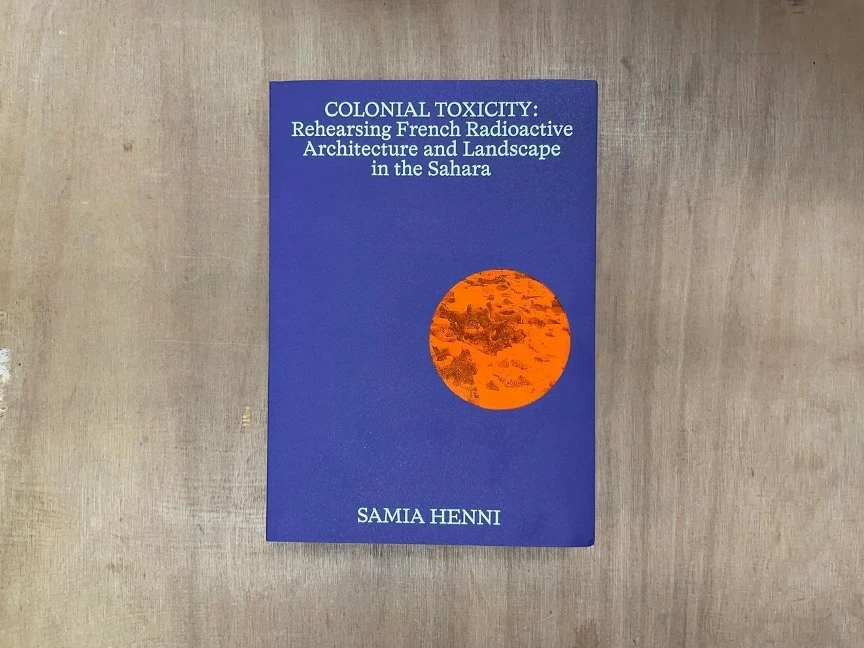

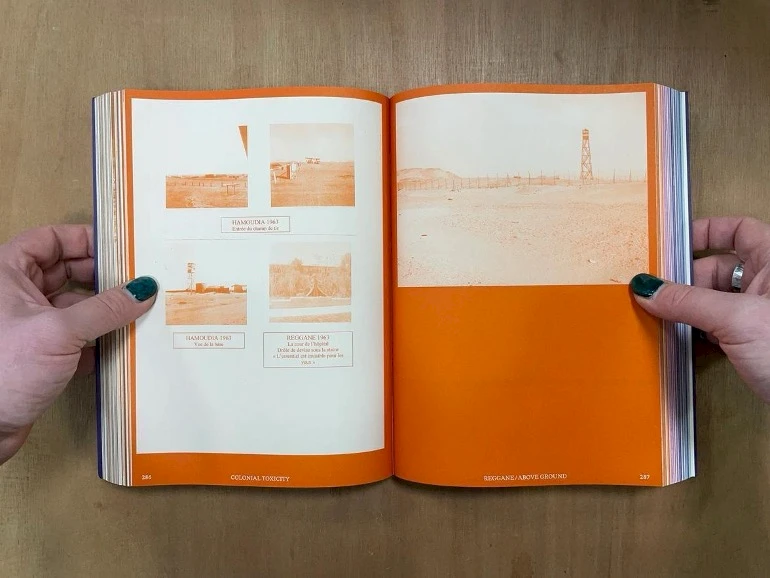

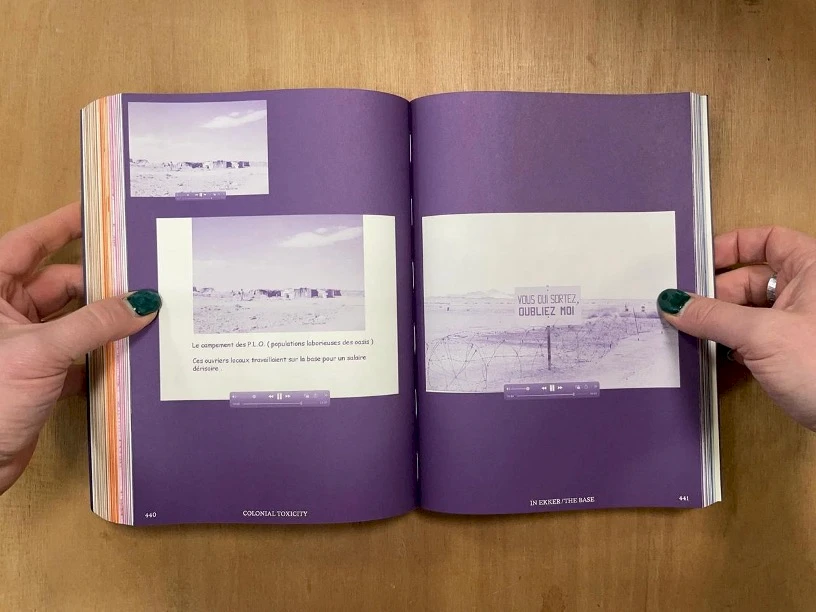

The last iteration of this project was the book Colonial Toxicity: Rehearsing French Radioactive Architecture and Landscape in the Sahara.5 It is a rich repository that brings together nearly six hundred pages of materials documenting this violent history of France’s nuclear bomb-testing programme in the Algerian desert. It addresses all those concerned with histories of nuclear weapons and those engaged at the intersections of spatial, social and environmental justice, as well as anticolonial archival practices.

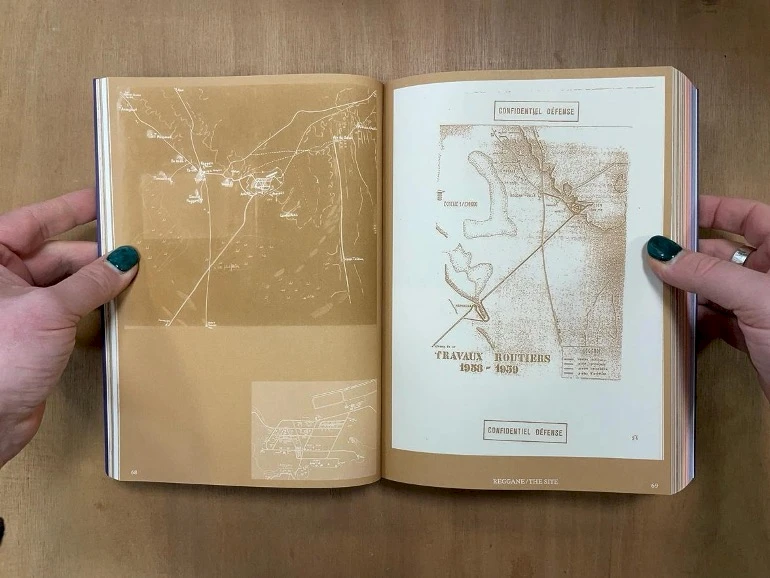

Samia Henni, Colonial Toxicity: Rehearsing French Radioactive Architecture and Land, 2024; front cover, contents, pages 68–69, 286–87,440–41, 540–41. Images courtesy Good Press

When one starts gathering and collecting, one becomes a sort of collector or archivist. There are almost no borders, no limits to that, but one has also to make choices. If the exhibition is organized around the stations with different titles, the book is structured according to two main categories: Reggane, where the atmospheric bombs were detonated, and In Ekker, where the underground bombs were exploded. So these sites guide the readers throughout the book. Each category encompasses a few chapters, such as ‘Construction Sites’, ‘Exposed Bodies’, and so on. The records that we worked with came from many different places and sources, so we had to find a way to organize this body of knowledge and make it as accessible as possible. With the graphic designer François Girard-Meunier, managing editor Megan Hoetger and contributing editor and publisher Georg Rütishauser, a series of coloured spaces were created within the pages of the book. Each chapter has a specific colour treatment so that readers can find coherence in reading the images that rest within the specific colour of that same chapter. These colours were inspired by the radioactive lava that came out of the uncontained underground bombs in the Sahara.

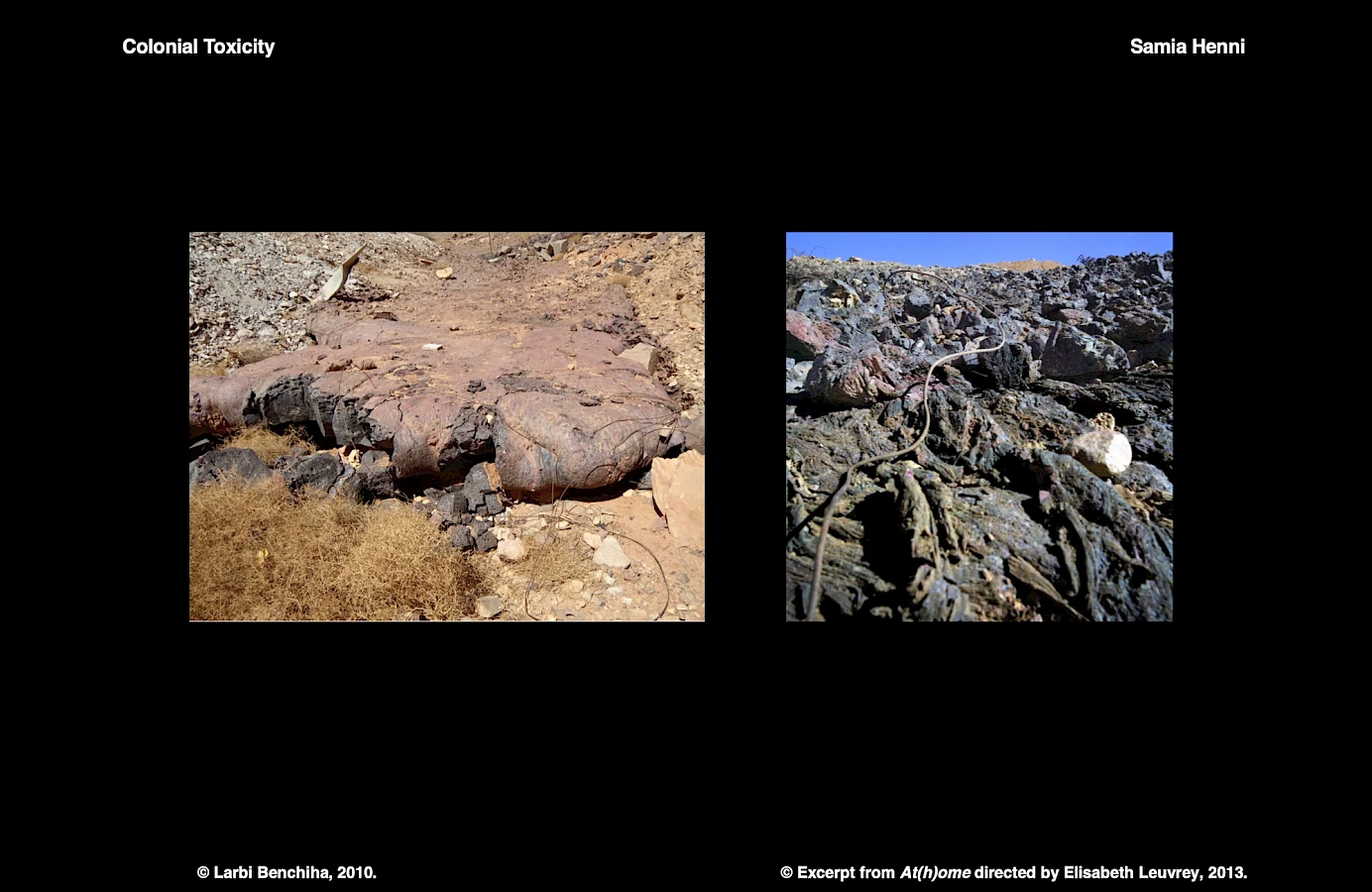

Left: photograph by Larbi Benchiha, 2010. Courtesy the artist. Right: photograph by Bruno Hadjih, as featured in A(t)Home, Elisabeth Leuvrey dir., France, Les Écrans du Large, 2013

On the left is a 2010 photograph by Algerian film-maker Larbi Benchiha. On the right is a photograph by Franco-Algerian photographer Bruno Hadjih, portrayed in Elisabeth Leuvrey’s 2013 documentary A(t)Home. Whereas Benchiha’s photograph portrays radioactive stone, lava that came out of Tan Afella mountain, Hadjih’s photograph illustrates the metamorphosis of contaminated stone that’s also radioactive. Both were generated by the heat and blast of a nuclear bomb. So we took this palette of colours to organize the book to show different tones of degradation. The book starts with an assembly and assemblage of images (rather than texts) so that readers might be overwhelmed with visuals that oppose and resist the imposed amnesia.

With this project and its forms of publicness (translating, exhibition and publishing), it is important to overcome the assertion that one cannot talk or write about these histories and lived realities because there is not enough evidence, or due to the classified status of institutional archives. Therefore, translating, exhibiting, searching, scanning, photographing, gathering, saving, assembling, indexing, arranging and rearranging the visuals is a means of documenting and ‘writing’ of colonial toxicity. It is not a French colonial or an Algerian story, history or event, as it has planetary consequences. Through sandstorms and wind, radioactivity has no boundaries. It travels all over the world. It is toxic. Colonialism is toxic. This toxicity is anthropogenic. It is irreversible, enduring and destructive.

NP-B: Thank you, Samia. I’m giving the floor to dear Marie-Hélène, who is in Tahiti right now, where it is 2.30 a.m., and to Mililani Ganivet, in London. Thank you for being with us at this late hour. I had the great pleasure to meet you both a year ago at Cité internationale des arts, where Marie-Hélène was a resident and where she introduced us to Mililani and to their collaboration. The following excerpts are from their video essay Nu/clear Stories (2024). It’s a collaboration between Marie-Hélène – an artist, photographer, producer and director from Mā’ohi Nui, or French-occupied Polynesia, who for thirty years has been documenting, visual testimonies of the transformation of the society and of the impact of coloniality on the society of the archipelago. Mililani, on the other hand, is from Tahiti and is currently doing a PhD at the Sainsbury Research Unit at the British Museum. She is also an activist and collaborator on several artistic projects, working most specifically on the consequences of thirty years of nuclear tests in the archipelagos of so-called Polynesia.

Mililani Ganivet: Thank you so much for having us and for taking the time to make our voices heard and represented. Before starting I would like to acknowledge Marie-Hélène’s work. We’ve been working together on this project but she’s been doing most of the work, weaving voices and stories together. The project started with thinking about thirty years of nuclear testing. We don’t come from the same generation. I was born just before the end of the nuclear testing, but both of us witnessed its long-lasting effects from different perspectives, and which are almost invisible today. It was important for us to have funding from the Pacific and not from France, so we remain independent. And, in a way, our podcast Nu/clear Stories is an act of resistance against what has been said about our people, while trying to amplify the voices of people that are not heard.

We try to make space for voices of people from other islands. In the podcast, we have decentred Tahiti to hear other islands close to the testing site. You’ll see a lot of the aspects that Samia has talked about in relation to language and testimony.

Marie-Hélène Villierme: For ocean people, stories are very important. They combine layers of truth, of reality, of imagination. For us, working with voices, and multiple languages, as they carry and mediate complex emotions – of guilt, of intimacy, and many more – we wanted to work on all the different layers of subtlety.

MG: Almost thirty years after the last French nuclear test was conducted in 1996, the people in what is today known as French Polynesia were still dealing with this violent colonial legacy. Between 1966 and 1996, France conducted 193 nuclear tests in French Polynesia. Today, the consequences of those tests are still perceptible, whether visible or not.

Polynesians and Tahitians, like many Indigenous peoples, have an important tradition of naming specific aspects of a person. So colonial toxicity, as Samia said, was also imposed on Indigenous peoples and environments through practices of naming – imposed not only just on the landscape and people, but also on their genealogies. Like ‘Canopus’, the code name for the first thermonuclear bomb in 1968 – the story of Canopus is very well known in Mangareva and the rest of French Polynesia. You realize how mapping these stories upon the lands and the people also consisted of renaming. It tells you a lot about the disruptive and deeply problematic aspects of colonial toxicity that are not immediately apparent – something that really struck us during our fieldwork.

So, that’s a brief word on the importance of naming and the impact of nuclear testing on the minds, peoples and landscapes of many generations and their ties to the land.

M-HV: I would like to introduce the second excerpt, which is centred on environmental issues and how the narrative of the French government tried to create confusion among local people. The excerpt touches on how the official narrative tried to shake local knowledge of ciguatera poisoning that affects corals.

MG: From 1963 the Pacific testing centre gradually became part of the lives of the inhabitants of Mangareva. Torn between feelings of curiosity and uncertainty, Mangarevans quickly adjusted to the visible presence of the newcomers on their island, whether they were military or civilian. How did the Pacific Testing Centre change their lives? What were the obvious, but also the more subtle disruptions that shook the daily life of this island, which is barely fifteen square kilometres in size?

If we are to think about colonial toxicity in the context of French Polynesia, it is vital to address mental confusion as an effect of not knowing about the direct and indirect consequences of the testing. There is a refusal to think holistically and take into account how mindscapes, landscapes and mental health are all related and connected.

In the course of the twenty-minute interviews we conducted, people would say something and then gradually change their perspective. The fact that we knew about some of the consequences now plagues us and prevents us from shedding light on it today. As a people, collectively, it’s been really hard to deal with that issue in particular – to acknowledge there were things we knew. That’s one instance of the pervasive aspects of nuclear testing that may not be initially apparent. And when you start talking to different communities, you realize how deep the consequences are.

NP-B: Thank you so much Marie-Hélène and Mililani. We now end with Olivier Marboeuf. Olivier is an author and a storyteller – we have heard a lot today about the importance of stories – that’s something that comes from your long-term practice in visual arts, the curatorial, poetry and film production, living between Guadeloupe and hexagonal France. Through institutional work, but also through artistic research, Olivier has been addressing many of the questions that are at the heart of France’s colonial legacies. I had the pleasure to meet Olivier through the work that he led at Kiasma between 2004 and 2018. Kiasma was, we might say, one of the first attempts to bring together knowledges of visual culture, of activism, of theoretical thought; situated in the north of Paris, a space where coloniality, postcolonialism and decoloniality were thought through and interrogated very precisely with and for its local public. Today you are part of the RAY|RAYO|RAYON Inter-Caribbean Network of Research and Art Education and part of the Akademie der Künste, among many other things. For those who might have been to Venice, we presented your work there in April 2024 in the exhibition ‘When Solidarity Is Not a Metaphor’.

Olivier Marboeuf: Thank you very much Nataša. Thank you so much for the two preceding presentations that point to the core of what I would like to talk about. They allow me to expand in other directions, even though I could unfortunately do the same kind of exposé in relation to the Caribbean, as you may imagine: not to speak about nuclear tests, but about the toxic economies of sugar, bananas, coffee and cotton. But I would like to discuss another aspect of this conversation that crossed your presentations, which is the issue of archives.

First, I would like to underscore that colonial apparatus is, at its core, a machine of erasure and destruction. It’s important to name in the most precise way the vocabulary of colonial violence to try to anticipate its repetition. The particular kind of destruction we are talking about always takes place in spaces considered as savage: terra nullius (‘nobody’s land’), places supposedly empty of people and forms of civilization, places without master. So, even if you could find people in the Sahara, in Polynesia, as you could find some in the Caribbean, the destruction of those people was allowed by the denial of their humanity. This is a radical principle shared by these three situations: the refusal to acknowledge the humanity of the beings living there, and of course of the set of reciprocal relationships they share with nonhuman entities, visible and invisible. This is the refusal of a world, of a cosmogony, a mode of entanglement – of an interdependent way of being human. This denial of another humanity and civilization is the central condition of Western modernity. It allows a radical destruction by emptying a space of its own history in order to have a moral licence to exploit the land in a way that Western civilization thinks that the exploitation of a territory should function. This is a way to produce everywhere a year zero, a new calendar, a new history without precedent. That’s why we could say that a colonial genocide is always an ecocide and an epistemicide at the same time. And as we saw in the contexts of Algeria and Polynesia, a radical destruction of a world can be quick, or it can happen very slowly, too, over a very long period of time.

And so now the question is: How are we to repair? What can we do with that colonial legacy? How can we deal with it? How can we rebuild a world from its toxic ruins? From what kinds of traces and traditions shall we draw? From what kind of technics and knowledge? What kind of humanity? There are different ways of working towards that; we have already touched on some of them here. The first step is to recompose an archive from scattered, lost, damaged stories. It’s not enough, but it’s a very important step, I would say. Afterwards, the task is to develop from it a practice of repair. The difficulty with the territories we’re talking about, historically colonized by France, is that today they’re caught up in an interweaving of different traditions. They are partly westernized, and we therefore tend to approach colonial destruction with tools that are themselves fairly westernized. This is the case when we insist on renaming: the act of affixing one’s name like a mark over another name is a typically Western obsession that aims to appropriate a thing, a land, a body. And, as we’ve said, it produces an epistemicide, erasing in the process all the variety of ways of understanding the world and the stories they carry, the genealogies. The same applies to the primacy accorded in Western culture to the visible over the other senses, and how the visible determines what exists and has value. This is where the demand for minority visibility is troubling. It is the very nature – and at the same time the paradox – of any policy of reparation based on recognition to validate a certain dominant gaze.So I have the feeling that we’re caught up in the master’s desires, or at least in desires that are similar to those of the master, that our way of imagining repair is dependent on the master’s tools. What concerns me is the need to imagine other tools that aren’t based on recognition, gestures that invent other regimes of the visible capable of translating other ways of being present.

We could also say that these tools do not in fact belong totally to the master, or not only. For enslaved people, for example, who always refused, every day of their lives, with every breath, to become totally the master’s objects. They resisted, and in return the master himself became possessed by these supposed objects, which he knew full well were in fact human. And this thought plunged his own life into a turmoil of his own making, as he accepted this pact of violence that would henceforth accompany and haunt him. Agreeing to treat human beings as disposable objects, fungible materials – to treat Indigenous populations as pests whose lives can be disposed of and whose deaths can be decided – is not without consequences. It opens up a chasm in the ethics of the living, while radically extending the limits of the exploitation of bodies and of a world that is no longer anything other than a vast collection of resources. It undoubtedly produces a category of humans who have lost many of their attachments to the world through capitalist necessities, and who are haunted by this particular right to violence.

The Martiniquan thinker and politician Aimé Césaire spoke of a ‘boomerang effect’, in French ‘un choc en retour’, to describe the phenomenon of the fatal return to the heart of the Western world itself of what had happened elsewhere, during the colonial period. This is exactly what happened with Nazism and the extermination of Europe’s Jews, and what is happening again today. The consequences of colonial destruction are therefore not only an expansion of violence in masterless lands, but also an involution of this violence in Western societies. And I obviously include Israel in this Western history as a power that produces violence: against the Palestinians by animalizing them, and against itself in a paradoxical process that is both existential and self-destructive.

So now we too are totally caught up in this process of capitalistic self-destruction as subjects of Empire. How can we get out of it? How can we oppose it? How do we build the conditions and ethics of a place of reparation? And how do we do this by refusing to demand recognition and visibility from powers whose economic and existential basis is precisely the denial of a whole range of human and nonhuman worlds to which we belong or wish to belong.

These are obviously very vast questions, and we need to try and determine the scales on which they can be answered. So, for today’s discussion at least, we need to ask ourselves what art can do in this matter, to what extent it can contribute to the beginning of a response or initiate a place for this response; in other words, how it can help define the conditions. Given that we have to show images as evidence of colonial destruction, that they are sometimes necessary – even if never sufficient – in a judicial context, what more can we artists and art professionals do?

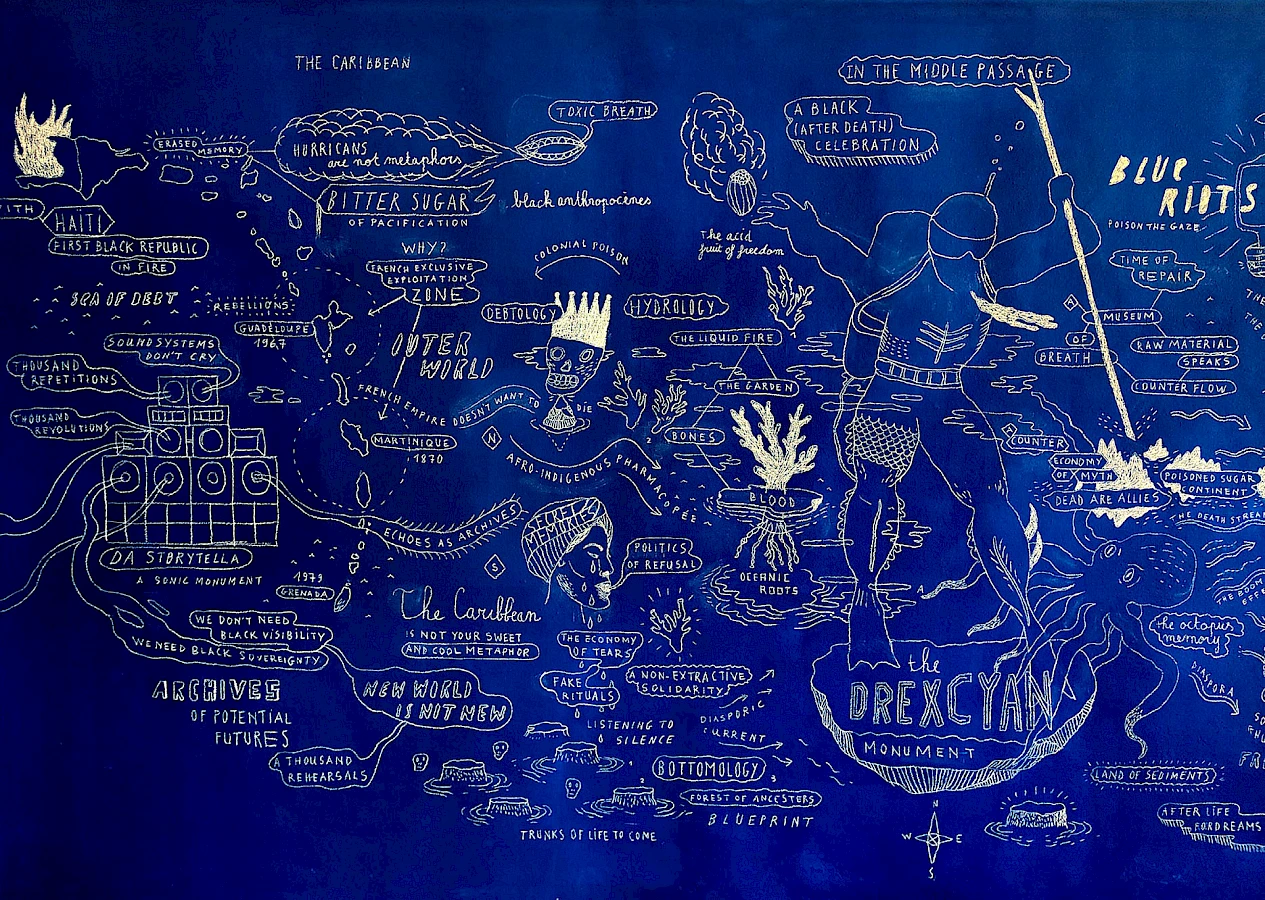

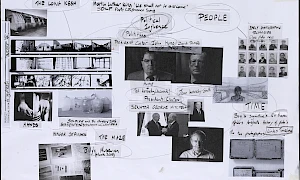

On this matter, I’d like to talk about a series of graphic experiments I’ve been developing recently, with the support of Nataša in particular, the aim of which is to weave together fragments of minority histories that appear in an indexical form; histories that beckon to some more than to others, that remain partially indecipherable, cryptic for a whole set of people – like captions that evoke images that aren’t quite there, images that aren’t shown, but that produce a ghostly presence. I prefer not to call these attempts drawings, but rather annotations, to follow in Christina Sharpe’s footsteps when she talks about annotating images in her book In the Wake: On Blackness and Being.6 The annotation technique she evokes is a gesture to be understood in relation to Black lives in the West, which find themselves literally overwhelmed by images, and in particular by images of themselves taken by others, by images captured by the white gaze and technologies. And these images that capture them in moments of ecstasy, shame or suffering, these images that are both libidinous and sad at the same time – the technique of annotation makes it possible, to a certain extent, to respond to them with something other than simply other images supposedly more dignified, more just.

Olivier Marboeuf, Museum of Breath, A liquid Monument (fragment), wall-drawing as part of the show ‘When Solidarity is Not a Metaphor’, curated by Simona Dvorak, Natasa Patresin Bachlez and Zaina Zaarour, Venice Biennale 2024. Photo: Ivan Erofeev

Annotation is a nonheroic intervention. By affixing discreet signs, a few words and captions, perhaps even traces of irony and humour, the obscure fragments of a poem, it breaks the symmetry of the response, signifying a fleeting presence, a presence that has taken leave of this scene of representation and recognition. Annotation is a way of confusing and saturating the meaning of the minority presence, which becomes equivocal and elusive. This reflection, this practice of annotation has kept me particularly busy over the last few years, insofar as it makes it possible to signify what is not quite there. To evoke presences without needing to show them, to welcome the spectres of those who were rejected on the margins of humanity. The annotation is a declaration of fleeting presence, the trace of an excess of presence and absence at the same time. Absenting ourselves from the table of dominant conversation, its terms and regulations, is also a way of saying that we need another table, elsewhere, other conditions of conversation. Are we capable of leaving this dominant table and abandoning our claims and demands for recognition at the same time? Can we imagine an active policy of refusal to influence the conditions of negotiation here, but from elsewhere, from outside the major art institutions in particular? It’s a difficult challenge, but one that can be built from a multitude of small refusals, small acts of marronage that announce another place and destabilize the recognition scene.

Nataša underlined how deeply interdependent art and culture workers are. This leads us to broaden the way we reconsider the conditions and scope of artistic gestures. Reflecting on our own practices of display and archival production from a reparative perspective is not just a question of content, it’s also a question of place. In what places are the reparations we’re talking about possible?

At the beginning of 2024, Nataša curated an exhibition with the artist and researcher Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, ‘La Mémoire des Hauts-fonds’. ‘Hauts-fonds’ means ‘shoals’, places that are neither quite land nor quite sea, but in-between, shifting spaces. This exhibition itself echoed the book The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies by Tiffany Lethabo King,7 which attempted to imagine sites of expression and protest, but also of encounter, between Indigenous and Black cultures in the Americas, in short, other tables of negotiation and minority alliances. What’s interesting about shoals is the idea of non-institutional, unstable places, with no master and no control. Here, the idea of a place without master is no longer the result of a denial of the presence of the Other but, on the contrary, the expression of a desire to consider all the intensities of presence/absence that hold and sustain that place, from near and far, and to give them equal value whether they are visible or invisible. Taking shoals seriously allows us to approach reparation as the search for and production of unstable situations, if we consider shared instability as a condition that makes a true experience of equality tangible – as in the mangrove. From a minority perspective, it will always be more interesting to propose that the conversation take place in these places of instability, these shoals where some have found refuge and learned to stand.

It was with these places in mind, and how to produce them – for they are not just physical places, but also relational ones – that I speculated, in one of my recent essays on ‘bewitched mediation’.8 This is a practice that displaces the classic function of cultural mediation in art institutions to turn it into a wandering form of collective ritual – the ‘place’ where a community of interpreters meets, negotiates and translates. A place where, far from the institution, we learn things we can’t know on our own, but also, and above all, things we didn’t know we wanted to know. ‘Bewitched mediation’ makes the mediator’s body now both medium and milieu: the central tool in the production of the archive and the site of an unstable tradition constantly calling for new repetitions. This is a way for me to consider the practice of the archive as reparative and to produce this archive at the same time as we produce our place of enunciation, without using the tools of recording, production and display that are part of the colonial heritage and its extractivist principles.

Of course, what particularly interested me about the cultural mediator is that they are a minor figure in the art institution, who doesn’t enjoy the same consideration and symbolic capital as the artist, curator or critic. Working with this minor figure was a strategy for reconstructing a scene of conversation and reparation, which I decided to gradually move outside the institution, away from its discourse and power of subordination. However, this fugitive scene continues to exert a form of influence from a distance, as I said earlier about this scene of refusal that no longer demands to be recognized, but whose presence, somewhere in the vicinity of the institution, changes the conditions of the majority conversation. Just as the encampments of the maroon communities, not far from the plantation, gradually changed its conditions and discourse through the effect of a phantom threat and the possibility of a life that is other but close at hand. This is why I call this collective performance ‘bewitched mediation’, which is necessary to maintain and sustain the archive. In a way, it is opposed to the idea of preserving the archive identically, just as it is opposed to the idea of a proprietary archive. In the intertwining of languages and words, this archive has no name, but it does have requirements, foremost among which is the need to always remake it, reproduce it, replay it, again and again. I know that in the traditions of the places we are talking about, in Saharan traditions, in Polynesian traditions, in Caribbean traditions, the practice of transmission is also based on the rehearsing and the repetition of the same stories. Which leads me to say that what has been destroyed by colonization is not only the variety of life forms, but also the variety of ways of preserving and reproducing life. So we need to be concerned with how to produce and reproduce the possibilities of life through our artistic practices. Because I have the impression that we sometimes accept rather mortifying ways of producing images of life in place of these possibilities of life.I wanted to share these ideas so that we could think together about a way forward.

[Addresses the panel:] How can we move forward on the basis of all the artistic work and research you’ve done, which is a necessary first step in the face of the denial of the existence of certain stories, certain acts of violence and tragic events? How do we deal with the denial of the long-term impact of such radical destruction? What other tactics are available to us to transform these tragic situations and invent modes of reparation on our own scale? This is what I’d like to discuss with you.

NP-B: Thank you so much Olivier. Arising from what we heard from Olivier is one of the questions that we wanted to have in this assembly, namely: What is a way out from institutions that have been infused with colonial violence, a violence that has been their modus operandi? What does this mean for the future of institutions? Should they exist? We are speaking of and from within fields of artistic research that operate with precision and patience, collecting stories and evidence not yet disclosed to the general public. We have heard from Samia about the importance of publicness and from Mililani and Marie-Hélène about the condition of unstableness or instability. I talked from the beginning about impunity, which for me is a core issue. In order not to talk about guilt, but rather debt, I think it’s very important not to have a moralistic discussion, but to know and use other operational tools.

SH: First of all, thank you Nataša for bringing us together. I think it makes so much sense. Olivier – you created many intersections, and you also confronted us in a way. I have a reflection: What I’m trying to do, like you mentioned, Olivier, it’s not enough. The question you ask is: How do we repair? I’m not there yet, to be very honest. I’m still very much stuck in the first phase. Maybe the question is, who has to repair? Not even who is expected to repair, but who has to repair. And that’s also why I am in this very first phase, documenting and addressing it to the West. Lots of people ask me if I will show this in Algeria. And the answer is no. They know it, they live in it! The public, the audience, the target for me is the West. When I talk about the West it is not only France and London, it’s also the US, it’s also all those who sign the contract of the destruction of Earth through the colonial project, which is ongoing . So the reflection or the question or the struggle I am facing is: Who has to repair?

M-HV: We are immersed in a process of reparation. Even if it’s very hard in reality and a very hard trauma to dig out of. We are trying to move towards a posture of affirmation. The time of revolution is obsolete – we now need to affirm ourselves, affirm our identity and affirm what our story is and the way we want to tell it, through Oceanian storytelling and Oceanian aesthetics.

MG: One thing that we don’t talk about often, in places like Algeria or French Polynesia, is how to create a safe space for people to be able to articulate complex emotions. Telling their stories is a form of healing that we often underestimate. We did it through a podcast, because we wanted to make our voices and story salient, but we were also both thinking about our own processes of healing. What we found is that by making the time, talking to people, not extracting from them was a way to set a space for collective healing. Often, researchers come, extract information and leave. For us, taking time and care with people, showing trust and empathy, was central to the process. And that safe space is an ongoing thing. It is a form of healing that is often underestimated.

At the same time as we carve that space for ourselves, we also like being present in institutions, as a way to talk, to show that we still exist – and being very adamant about that. So I think based on what Olivier was saying, we’re kind of facing in two directions, which I think are not mutually exclusive but can co-exist: To be anchored in what we know, and to set that space that makes our voices stronger; and to resonate louder outside our respective contexts.

OM: I agree that there are no exclusive phases. When I talk about phases, I think that the time of reclamation is normal. The first way of reacting is to reclaim something and to assemble some evidence. I’m just saying that we have to switch, at a certain moment, to another time and mode of operation. That doesn’t mean that the first phase doesn’t exist anymore. We are all in the Western world and outside of it at the same time. We are moving between different positionalities. And as you said, even the space to record voices and to host people is already that kind of shoal I’m talking about. It doesn’t have to be big, just a space where people can say what they feel and speak with their own language and through their own experience. We need to collect fragile precedents. We also have to accept that we can’t act heroically, and that we have to work in modest spaces. We have to learn to honour these small spaces, to give them a certain value. We mustn’t underestimate them because they really do contain the reproductive potential I mentioned earlier.

NP-B: Olivier mentioned earlier our collaborative curatorial work with Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc at the Cité internationale des arts, where the discussions we had with Mathieu and with the participating artists revolved around Tiffany Lethabo King’s intersectional understanding of shoals as safe spaces despite their moving with unpredictability. Listening to you also made me realize that safe spaces should be considered as unstable spaces. And that shoals can and should be claimed as safe spaces.

OM: Yes, but instability is a natural space.

NP-B: Exactly. There is a question from Adeola Enigbokan to Olivier: How can we use bodies that are institutionalized, colonial and colonized to reproduce and rehearse body recordings that do not conform to institutional tools and practices?

OM: It’s a very important question, which sounds a bit like a dead end insofar as contemporary art institutions seem to enjoy this incredible plasticity that enables them to absorb minority practices more and more every day. It’s in the very nature of capitalism that they have become the privileged tools of ‘soft power’. This gives the impression that all minority gestures quickly become institutional commodities. But we are in fact partly responsible for this because of what we believe to be a desire, which is in fact an injunction: we want to be in these places to prove the value of our existence, to prove that we are up to scratch, that we are professionals. It’s a question that’s currently preoccupying me a great deal, as I’m in the process of thinking about the best form to give to the archive of my own experiences in relation to the question of art institutions, as my path has been built essentially from independent places and thanks to marginal and accidental interactions. If you want to keep certain practices alive, you have to resist the injunction to become a professional. It’s not easy, because everything pushes you to become one, as if to prove that you have the right to be there, that you’re legitimate. And I believe we must do our best to distance ourselves from this demand made on Western institutions that they should validate our humanity. For it is the very legacy of colonization to make us believe that some people are more human than others, more worthy than others, and that they can thus validate the existence of others, the gestures and civilization of others – as at the time of the Valladolid Controversy, when the Spaniards gave themselves the divine right to discuss the degree of humanity of the Native Americans in their absence. This is something we need to keep in mind when we find ourselves as a minority body in a Western institution, because there is a long history that is sedimented and working in the underbelly of this scene, which is itself nothing more than the toxic repetition of a very old scene of violence. I know today that in accepting to gradually become an art professional, I made a mistake that I’ve been trying to get out of for a number of years in order to return to my first intuitions, which were more just and profound desires. So it’s important to maintain practices considered non-professional, which are safer places for sharing. To escape the trap of visibility, we must therefore accept practices that are not immediately visible and reject the idea that visibility is the only desirable form of existence. We must remember that the famously ‘savage’ world, terra nullius, was not an empty space, but a place filled with presences, signs and attachments that were invisible only to the settler who was unwilling to enter into any relationship other than that of taking. The grip of land, the grip of lives: in his famous poem ‘The Sea Is History’, St. Lucian poet Derek Walcott proposes a real strategy in the face of the demand for visibility by settlers and their descendants. To the question, ‘Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs? / Where is your tribal memory?’, he replies: ‘Sirs, / in that grey vault. The sea. The sea has locked them up. The sea is History.’ He poses this enigmatic asymmetry rather than wanting to exist in the eyes of his enemies. And in this way, he opens up the possibility of another world, another archive and other regimes of existence than Western hypervisibility, in the rest of the poem and beyond. This is a very important poetic and political proposition for me.

NP-B: Thank you so much to all. It’s just the beginning of a long discussion, of finding stable instability, or rather, unstable stability.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–tranzit.ro

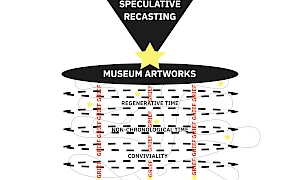

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

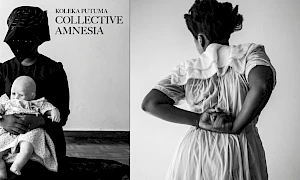

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations