Black Archives: Episode I. Radical Internationalism and Pan-Africanism in the context of the Spanish Civil War

In the first episode of a three-part series, curator, writer, researcher and founder-editor of Radio Africa Tania Safura Adam delves into the history of Pan-Africanism in Spain. Episode I examines how Pan-Africanist alliances in the wake of the colonial invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini mobilized Black anti-fascist struggles during the Spanish Civil War.

In August 1920, the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA), founded in 1914 by journalist and businessman Marcus Mosiah Garvey in Kingston, Jamaica, held its First International Convention in New York. After debates chaired by Garvey himself, with the participation of thousands of delegates from numerous countries, the ‘Declaration of Rights of the Negro Peoples of the World’ was adopted. This defended human rights relating to freedom and equal treatment before the law. The declaration concludes that Ethiopia is the ‘land of our fathers’, and ascribes to it a prophetic destiny by divine election. Thus, the ‘Universal Ethiopian Anthem’ (composed in 1918) became, with some modifications, the ‘Anthem of the Negro Race’1:

Ethiopia, thou land of our fathers,

Thou land where the gods loved to be:

As storm cloud at night suddenly gathers

Our armies come rushing to thee.

We must in the fight be victorious

When swords are thrust outward to gleam;

For us will the vict’ry be glorious

When led by the red, black and green.

Advance, advance to victory,

Let Africa be free;

Advance to meet the foe

With the might

Of the red, the black and the green.

Shall aliens continue to spoil us?

Shall despots continue their greed?

Refrain

Will nations in mock’ry revile us?

Then our keen swords intercede!

The song denotes Ethiopia, and Africa, as a national entity and its children are compared to those of the Jewish people, scattered in lands across the seas. The anthem reflects the Ethiopian nation as it was established under the UNIA’s motto: ‘One God, One Aim, One Destiny’. It was at this time that Garvey prophesied: ‘Look to Africa, when a black king shall be crowned, for the day of deliverance is at hand.’ Ten years later, in 1930, the prophecy was fulfilled with the coronation of Ras Tafari Makonnen, known as Haile Selassie I. Bearing the titles of ‘Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah’, ‘King of Kings’ and ‘Lord of Lords’, he would be the last emperor of Ethiopia.2

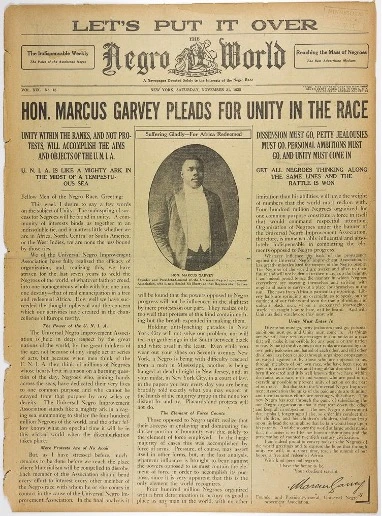

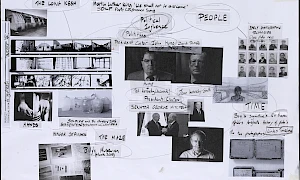

Negro World newspaper, 1925

However, the King of Kings had little time to enjoy his throne because, in 1935, a thousand Italian soldiers – led by the dictator Benito Mussolini, leader of the National Fascist Party – invaded Ethiopia without first declaring war. A few months earlier, on the other side of the Atlantic, in a New York City suffering from the effects of the Great Depression, three thousand people attended the first meeting of the Provisional Committee for the Defense of Ethiopia at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem. It was announced at that meeting that hundreds of volunteers from various political affiliations were ready to enlist in the Ethiopian army to defend the Black nation, which was increasingly under siege by Mussolini. These volunteers included Black nationalists recruited by the Communist Party after the arrest of Marcus Garvey in 1923 for alleged fraud, socialists and Pan-Africanists.

In her introduction to the Spanish edition of Mississippi to Madrid: Memoir of a Black American in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade by international brigadista (brigade fighter) and civil rights activist James Yates,3 journalist Mireia Sentís observes that many African Americans wanted to enlist to defend Ethiopia after the League of Nations decided not to intervene.4 The Abyssinian Baptist Church itself collected funds and supplies for Ethiopia and later for Spain. Fundraising and support campaigns also included benefit concerts by musicians such as Fats Waller, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Eubie Blake and Paul Robeson. However, the aid never arrived, as Selassie had warned: ‘Today it’s us, tomorrow it will be you.’ This discouraged African Americans from participating for fear of possible US reprisals.

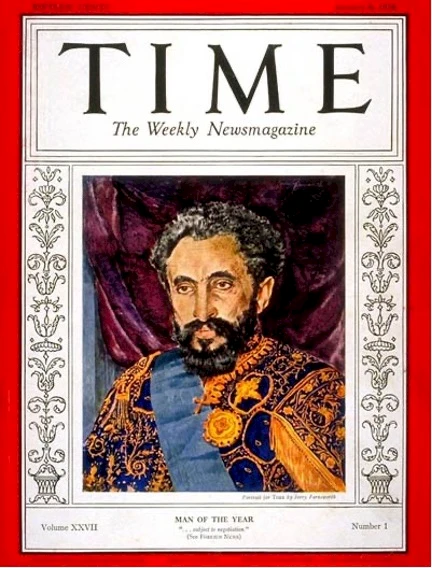

Haile Selassie on the cover of Time magazine, 6 January 1936

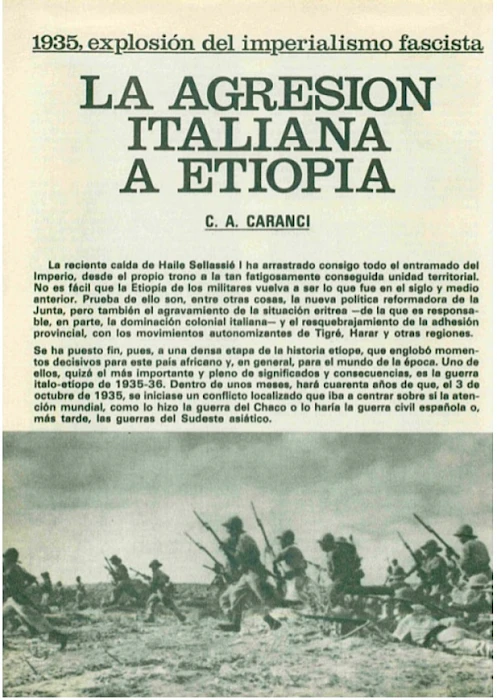

C.A. Caranci, ‘1935, Explosion of Fascist Imperialism: Italian aggression in Ethiopia’, 1935

Harlem anti-fascists saw Mussolini’s attacks as an attack against Black people everywhere. Even speakers on Harlem street corners warned passers-by of the need for global Black unity to oppose fascist militarism. Pan-Africanists argued that the security and wellbeing of African Americans were tied to Africa’s fate. Anti-imperialists insisted that the only country that had maintained its independence in a continent dominated by the onslaught of colonization must be defended. African American writer and poet Langston Hughes, a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance and an active fundraiser for Ethiopia, wrote the poem ‘Call of Ethiopia’ in 1935:

Ethiopia

Lift your night-dark face,

Abyssinian

Son of Sheba’s race!

Your palm trees tall

And your mountains high

Are shade and shelter

To men who die

For freedom’s sake —

But in the wake of your sacrifice

May all Africa arise

With blazing eyes and night-dark face

In answer to the call of Sheba’s race:Ethiopia’s free!

Be like me,

All of Africa,

Arise and be free!

All you black peoples,

Be free! Be free!

Abyssinian Baptist Church, Harlem, January 1928

The West’s refusal to support Ethiopia intensified Pan-Africanist solidarity and reinforced the growing sense of radical internationalism in the face of the 1936 fascist uprising against the Second Spanish Republic. After the frustrated efforts to help the former Abyssinia, Black Americans likened this new situation to that one, and rallied behind the Republican cause.

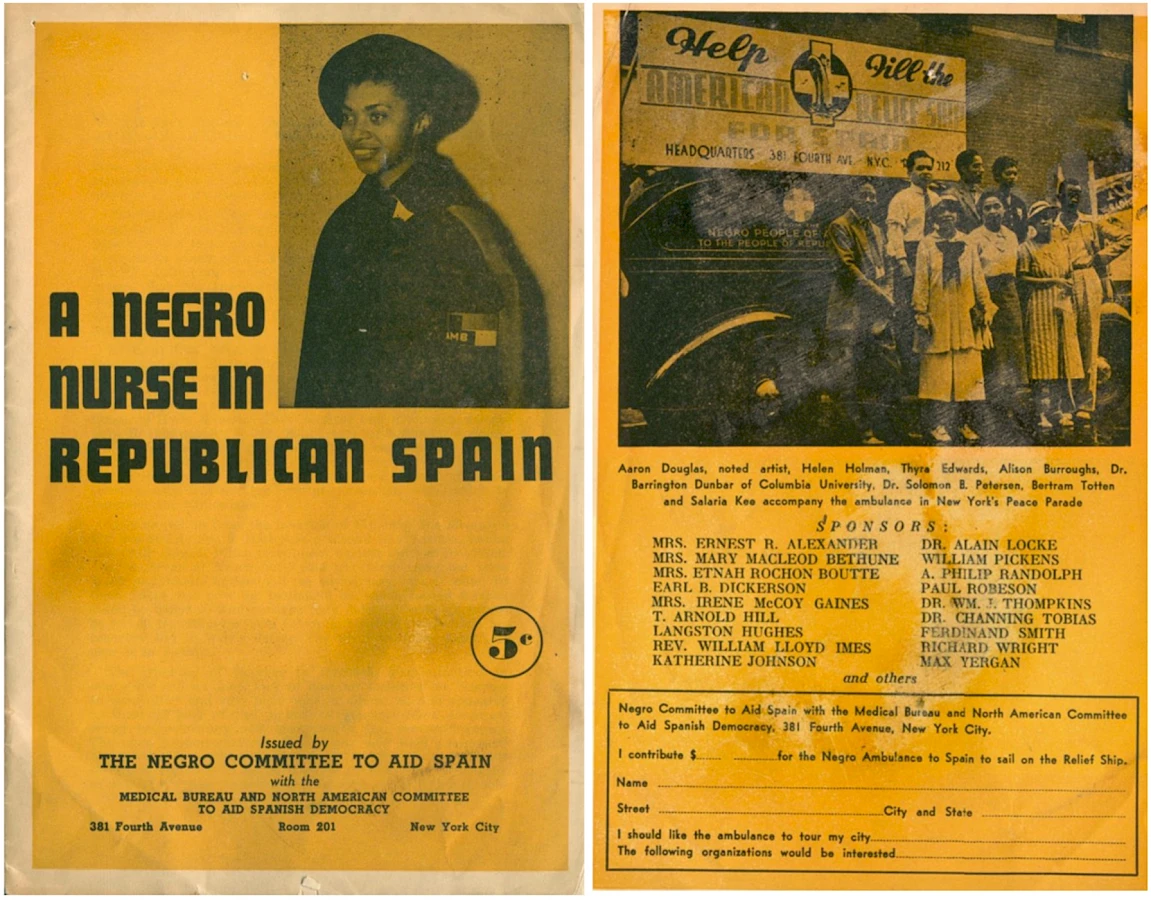

Salaria Kea, one of the nurses who accompanied the American contingent of the International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, explains the relationship between Ethiopia and Spain in A Black Nurse in Republican Spain (1938), a pamphlet published in New York by the Negro Committee to Aid Spain with the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy.5 Kea stresses that intervening in the Spanish conflict is a way of supporting the Black cause. She states: ‘Italy invaded and overpowered Ethiopia. This was a terrible blow to Negroes throughout the world.’ She argues in the booklet that Spain represents the battlefield on which Italian fascism must be defeated. According to the members of the Negro Committee, the only hope of regaining Ethiopia lay in defeating Italy. In other words, it was through Spain that Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany had to be defeated, because of their open pronouncements against all non-Aryans.

Salaria Kea, A Negro Nurse in Republican Spain, pamphlet, Negro Committee to Aid Spain with the Medical Bureau and North American Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy, 1938

The advance of fascism in Europe concerned African Americans to such an extent that, even though the United States had threatened to revoke the citizenship of anyone who enlisted in a foreign army, they joined the International Brigades through the Communist International (the Comintern). The Brigades were a coalition in defence of the Republic of Spain, bringing together multiethnic and multinational volunteer troops from fifty-three countries. Many of these Black Americans were members of the Communist Party. The Abraham Lincoln Brigade (ALB) was created as the first nonsegregated fighting force, with 3,000 Americans and at least ninety African Americans, who entered Spain illegally and fought against Franco’s regime alongside other volunteers from Djibouti, South Africa, Cuba, Senegal, Haiti, Cameroon and elsewhere.

In ‘Not Valid for Spain: Pan-Africanism, Sanctuary, and the Spanish Civil War’, published in Black USA and Spain: Shared Memories in the 20th Century, Karen W. Martin also refers

to the impulse to fight fascism abroad as a means of combating racism – described by many brigadistas as domestic fascism – in the United States; and to the awareness of the shared fate of Jews and Blacks as two populations targeted for genocide by Hitler’s mythical white German race.6

The post-war period and the economic and social malaise of the 1920s in the United States were the driving forces behind this Pan-African community building. Prominent figures of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Claude McKay and W.E.B. Du Bois, worked to build a sense of community identity in a situation where they were once again confronted by the forces of white supremacy and a revitalized Ku Klux Klan, as D.W. Griffith’s 1915 film The Birth of a Nation aptly reflects. Black Americans had already experienced fascism at home, from slavery through to Jim Crow laws and policies, and sensed that if European fascism spread across the Atlantic, they would be hardest hit.

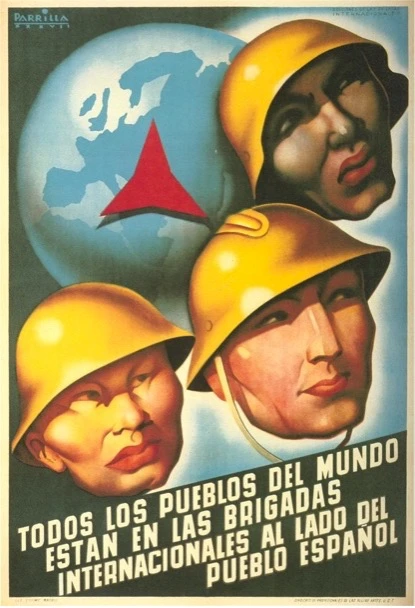

Parrilla, ‘Todos los pueblos del mundo estan en las Brigadas Internacionales al lado del pueblo espanol’ (All the peoples of the world are in the International Brigades on the side of the Spanish people), Brigadas Internacionales, Sindicato de Profesionales de las Bellas Artes, n.d., Pavilion of the Republic Collection

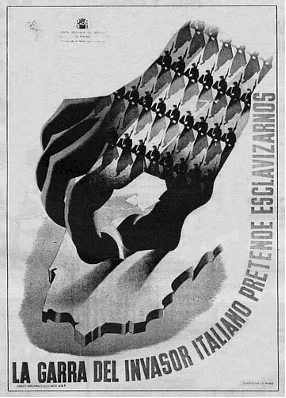

Amado Mauprivez Oliver, ‘La garra del invasor italiano pretended esclavizarnos’ (The claw of the Italian invader intends to enslave us), 1936

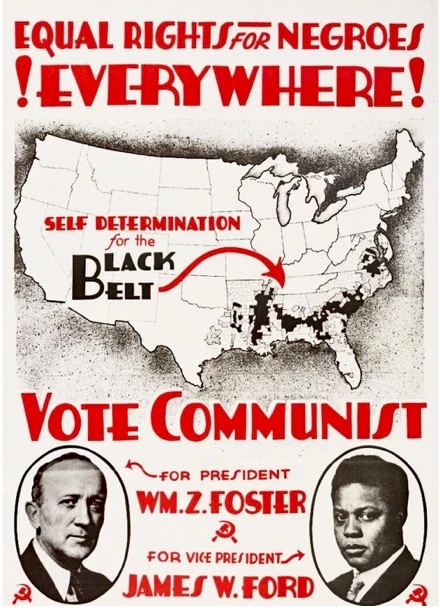

US Communist Party presidential campaign poster calling for ‘Equal rights for negroes everywhere!’, 1932

Pan-African engagement in the struggle against the advance of Italian fascism in Ethiopia, and the conviction that the spread of American fascism would intensify violence and racial discrimination are also evident in Robert F. Reid-Pharr’s Archives of Flesh: African America, Spain, and Post-Humanist Critique (2016), which points to the intellectual engagement between Black America and Republican Spain.7 It also accuses key institutions of Western humanism – such as colleges and universities – of developing an intimate relationship with slavery, colonization and white supremacy.

In the same vein, at the close of the last century, in 1990, the historian and theorist Robin D.G. Kelley developed the idea of building ‘radical internationalism’ rooted in Pan-Africanism in the preface to the book African-Americans and the Spanish Civil War: ‘This Ain’t Ethiopia, But It’ll Do’, commissioned by the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA).8 In an interview also published on ALBA’s website, he points out:

Even before Franco’s troops invaded Spain, [Communist Party members like Angelo] Herndon and his comrades were calling on workers to fight Fascism at home … In one of his speeches, [Herndon] said: ‘Today, when the world is in danger of being pushed into another blood-bath, when Negroes are being shot down and lynched wholesale, when every sort of outrage is taking place against the masses of people – today is the time to act.’ Black radicals heeded Herndon’s plea ‘to act’, mobilizing in defence of Ethiopia, resisting lynch law in the South, organizing a global anti-colonial movement, and defending Republican Spain from the Fascists.9

The writer Langston Hughes was a war correspondent in Spain for the Baltimore Afro-American and the Cleveland Call & Post. In the midst of the Spanish Civil War, he participated in the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defence of Culture, which took place between 4 and 17 July 1937 in three cities in Republican Spain (Valencia, Madrid and Barcelona) and in Paris, with the support of the Alliance of Antifascist Intellectuals.10 Hughes delivered a speech at the conference that helped set the precedent in linking the fight against Spain’s Francoists to the battle against Mussolini and, like Salaria Kea, identified Spain as an indirect battleground in the Ethiopian conflict.

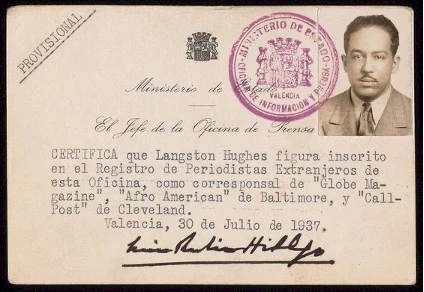

Langston Hughes’s accreditation as correspondent in Spain for the Globe Magazine, the Afro-American and the Call & Post, July 1937

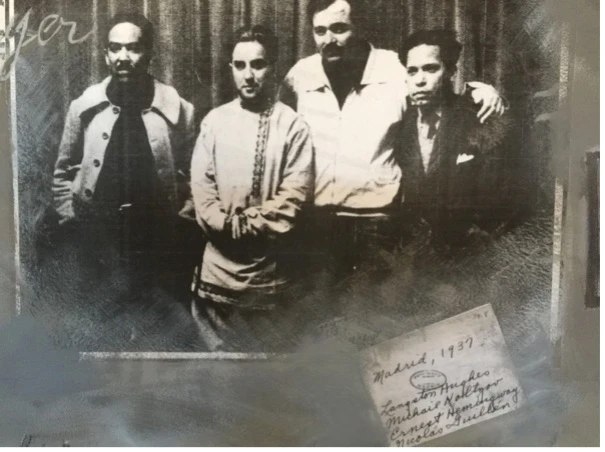

Langston Hughes, Soviet journalist Mikhail Koltsov, Ernest Hemingway and Cuban poet and journalist Nicolás Guillén in Madrid, 1937

Hughes’s prose from his time in Spain gives voice to the victims, for whom he felt immeasurable empathy, and his poetry rises up against those who brought the war to Spain. In his 1937 poem ‘Love Letter from Spain’, he points out the connection between European fascism and Jim Crow laws – domestic fascism.

… Just now I’m goin’

to take a fascist town.

Fascists is like Jim Crow peoples, honey —

And here we shoot ‘em down.

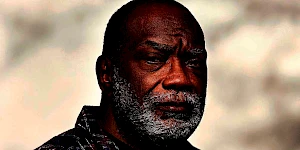

The singer and actor Paul Robeson, who had also raised funds for Ethiopia along with Kea and many others, became the voice of the anti-fascist resistance. Towards the end of 1937, after taking part in the demonstrations to ‘save Spain’, he announced to his wife Eslanda that he wanted to go to Spain. She urged him not to go, arguing that it was too dangerous, and he replied: ‘Spain’s our fight, my fight.’11

So, in January 1938, Paul and Eslanda Robeson arrived in Barcelona, from where they went on a tour of trenches, hospitals and camps to give concerts and boost the morale of wounded men, women and children.12 Wherever he appeared, volunteer soldiers from fifty-three nations would recognize him and greet him with a raised fist – the anti-fascist salute – and a powerful ‘¡Salud!’. Robeson said:

I have never seen a more courageous people. I went to Spain in 1938 and that was a major turning point in my life. There I saw it was the working men and women of Spain who were heroically giving ‘their last full measure of devotion’ to the cause of democracy in that bloody conflict, and that it was the upper class—the landed gentry, the bankers and industrialists—who had unleashed the fascist beast against their own people. From the ranks of the workers of other lands volunteers had come to help in the epic defence of Madrid, and in Spain I sang with my whole heart and soul for these gallant fighters of the International Brigade.13

Paul Robeson, Songs of Free Men, featuring the Spanish Loyalist song ‘The Four Insurgent Generals’ (remastered), Sony Classical Masterworks Heritage Series, 1997

Salaria Kea argued for revolutionary causes in speech and writing after the war, reinforcing the sense of solidarity that she, like many others in the International Brigades, had developed over the time she spent in Spain. She said: ‘Divisions of race and creed and religion and nationality lost significance when they met in Spain in a united effort to make Spain the tomb of fascism.’ However, Reid-Pharr shows some scepticism about the unified nature of the racial narrative of such oral testimonies. He notes that ‘they were extremely effective emblems of the leftist propaganda machine’, fitting in perfectly with the purposes of 1930s racial politics and the construction of the ‘New Negro.’ This is the ‘cosmopolitan Negro’ who rejects Jim Crow politics, as Committee member Alain Locke points out in his 1925 anthology of fiction, poetry and essays The New Negro.14 If indeed an illusion, it is a laudable one in the face of a reality in which Blacks were lynched, discriminated against in education and jobs, and denied access to hospital facilities in most cities in America.

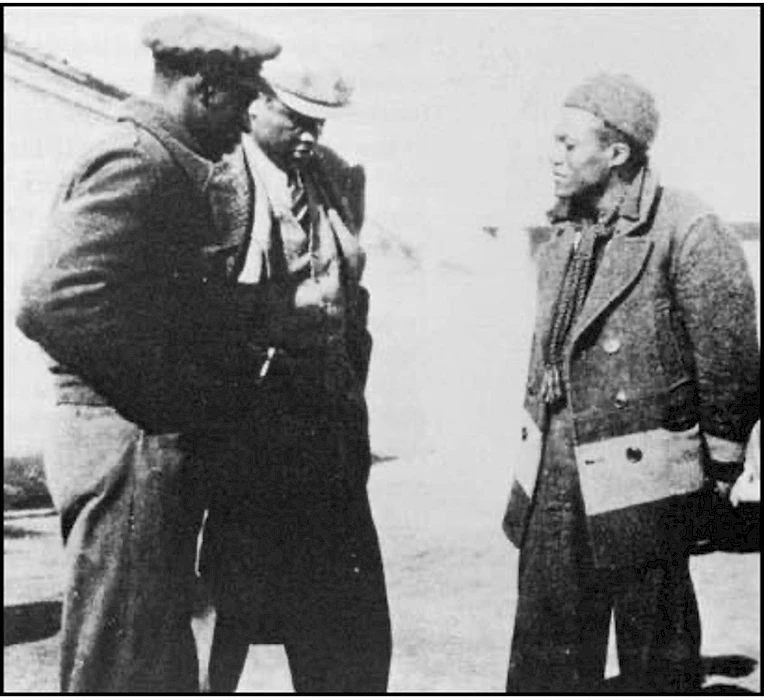

Paul Robeson with Oliver Law in Spain, 1937

Photo taken in Harlem, New York, of the campaign to fill a ship with humanitarian aid for Spain. Salaria Kea (left) is shown sitting on the running board of an ambulance donated to ALBA ‘From the Negro People of America to the People of Republican Spain’.

The reality in Spain was also harsh, and although there was a sense of freedom outside the chains of the Jim Crow restrictions, Hughes himself expressed it in his Spanish poems narrated by ‘Johnny’, a fictional soldier serving in the Lincoln Battalion. Johnny, as well as taking a Pan-African view, describes the raw reality of war. For example, he portrays the shock of the Black soldiers when they capture a ‘wounded Moor’ fighting on Franco’s side, in the poem ‘Letter from Spain’:

Dear brother at home:

We captured a wounded Moor today.

He was just as dark as me.

I said, Boy, what you been doin’ here

Fightin’ against the free?

He answered something in a language

I couldn’t understand.

But somebody told me he was sayin’

They nabbed him in his land

And made him join the fascist army

And come across to Spain.

And he said he had a feelin’

He’d never get back home again.

He said he had a feelin’

This whole thing wasn’t right.

He said he didn’t know

The folks he had to fight.

And as he lay there dying

In a village we had taken,

I looked across to Africa

And seed foundations shakin’.

Cause if a free Spain wins this war,

The colonies, too, are free —

Then something wonderful’ll happen

To them Moors as dark as me.

I said, I guess that’s why old England

And I reckon Italy, too,

Is afraid to let a workers’ Spain

Be too good to me and you —Cause they got slaves in Africa —

And they don’t want ’em to be free.

Listen, Moorish prisoner, hell!

Here, shake hands with me!

I knelt down there beside him,

And I took his hand —

But the wounded Moor was dyin’

And he didn’t understand.Salud,

Johnny15

The dying soldier manages to explain that he was taken from his home, supposedly Morocco, and forced to join a war he did not understand against an unknown enemy. The poem, as well as combining the three pillars of the Black brigadistas’ involvement in Spain – Pan-Africanism, the global struggle against fascism, and the racist oppression of Blacks both at home and abroad – highlights the cultural and geographical proximity between Spain and Africa. Indeed, Africa, rather than being portrayed as a distant ‘dark continent’, is connected to Spain through centuries of Arab history on the peninsula. Johnny’s poetic voice explicitly links fascism to colonialism in Africa. He realizes that other European nations oppose the Republic because empowering workers in Spain threatens the continuation of slavery and exploitation of Africans in European colonies. This is why Hughes perceived the victory of the Republic to be analogous to the liberation of the African colonies.

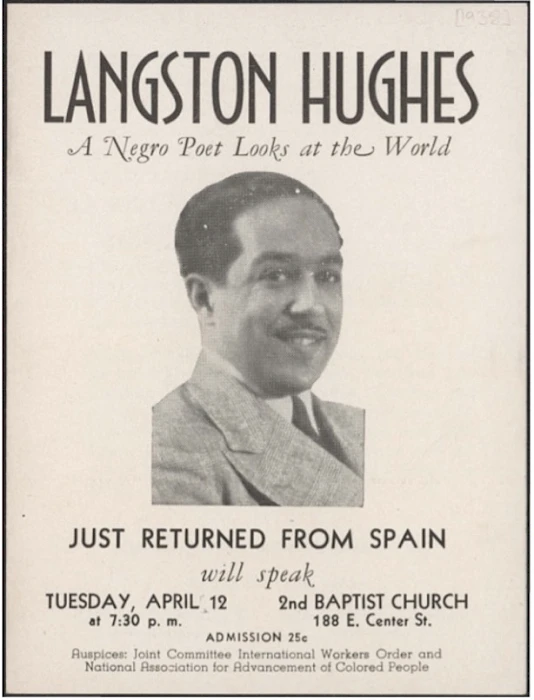

‘A Negro Poet Looks at the World’, poster for talk by Langston Hughes at 2nd Baptist Church, Akron, Ohio, 12 April 1938. Langston Hughes Ephemera Collection, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library

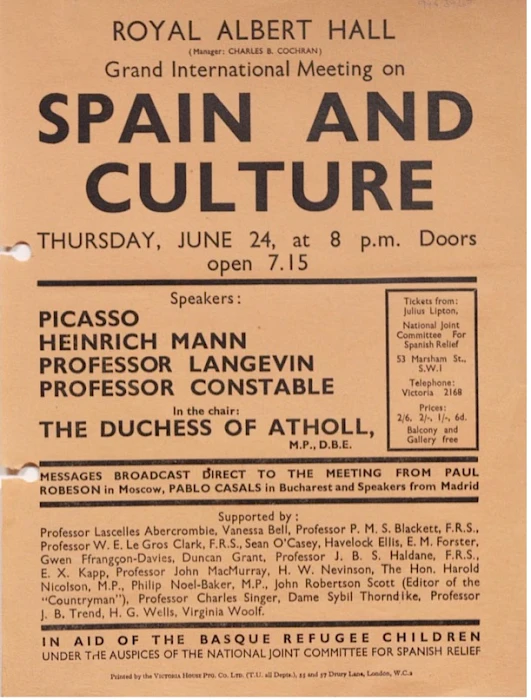

‘Spain and Culture’, poster for meeting at the Royal Albert Hall, London, 24 June 1937

Unfortunately, the Republicans were defeated by the pro-fascist dictator General Francisco Franco, who announced the end of the war on 1 April 1939.

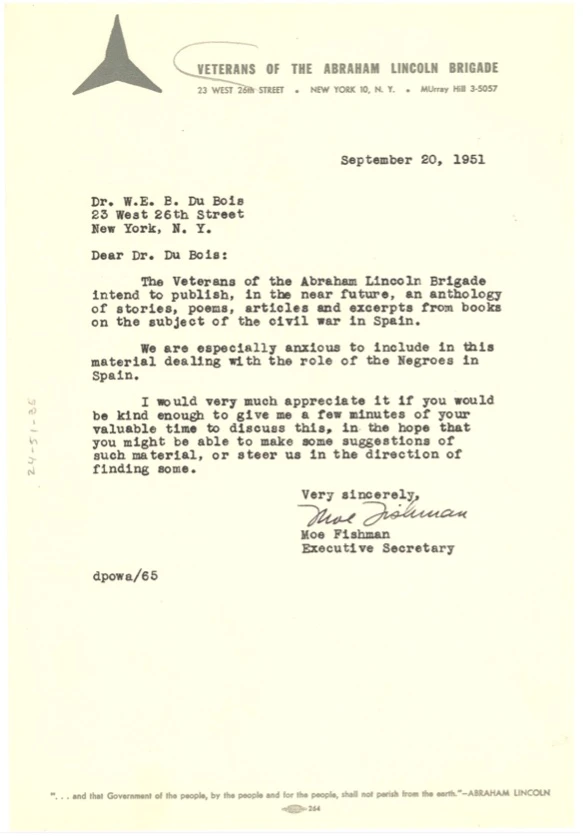

At the end of the war, the American survivors named Paul Robeson an honorary member of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Veterans. A decade later, aiming to ensure that his time in Spain would not be forgotten, they began compiling his memoirs.16 To this end, they wrote a letter to the sociologist, historian and Pan-Africanist W.E.B. Du Bois, in which they set out their intention to create an archive that would tell this story, and asked to meet to discuss their plans.

Letter from Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade to W.E.B. Du Bois, 20 September 1951

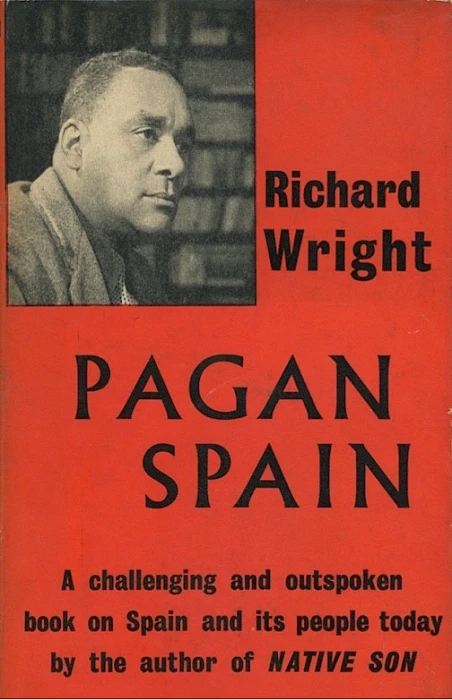

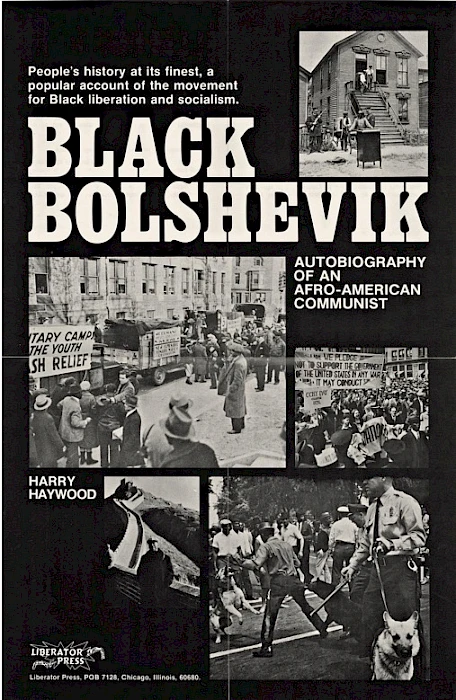

In addition to James Yates, Salaria Kea, Langston Hughes and Paul Robeson himself, other brigade volunteers shared their experiences with the public. These included the soldier Harry Haywood, author of his autobiography Black Bolshevik.17 Others were brought to the fore, such as Oliver Law, the first Black man to command a battalion in the history of the United States Armed Forces, killed in the 1937 Battle of Brunete.18 However, despite all the literature, their memories have been diluted. This is because of a lack of comprehensive documentation anywhere beyond the recollections and the dozens of archives, books, photographs and pamphlets that ALBA has been compiling and publishing. Even in the 1950s, when the writer, poet and member of the Negro Committee to Aid Spain Richard Wright travelled to Spain on Gertrude Stein’s recommendation, there were no memorials, just a country devastated by the war. Stein, who visited Spain on several occasions between 1911 and 1915, had told him:

You’ll see the past there. You’ll see what the Western world is made of. Spain is primitive, but lovely. And the people! There are no people such as the Spanish anywhere. I’ve spent days in Spain that I’ll never forget.

Cover of Richard Wright’s Pagan Spain, London: Bodley Head, 1960

Cover of Harry Haywood’s Black Bolshevik: Autobiography of an Afro-American Communist, 1978

Wright, who, having been a member of the Negro Committee to Aid Spain, already had some knowledge of the reality of the situation there, listened to her. His book Pagan Spain (1957) is the result of that trip and portrays a strange country, laden with stereotypes, and economically rundown. A controversial text that the New York Times called ‘provocative and disturbing’, it begins:

In torrid August, 1954, I was under the blue skies of the Midi, just a few hours from the Spanish frontier. To my right stretched the flat, green fields of southern France; to my left lay a sweep of sand beyond which the Mediterranean heaved and sparkled. I was alone. I had no commitments. Seated in my car, I held the steering wheel in my hands. I wanted to go to Spain, but something was holding me back. The only thing that stood between me and a Spain that beckoned as much as it repelled was a state of mind. God knows, totalitarian governments and ways of life were no mystery to me. I had been born under an absolutistic racist regime in Mississippi; I had lived and worked for twelve years under the political dictatorship of the Communist party of the United States; and I had spent a year of my life under the police terror Perón in Buenos Aires. So why avoid the reality of life under Franco? What was I scared of?19

Related activities

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

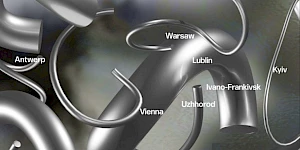

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

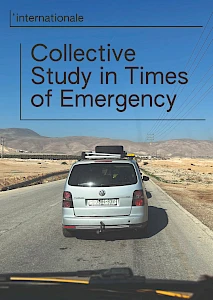

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

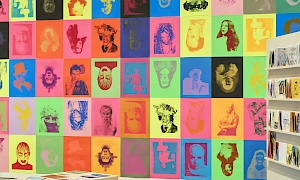

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

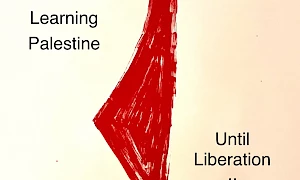

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials