S is for Silence

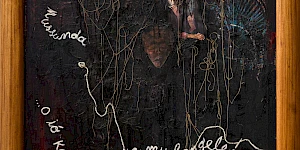

In this New Year letter cultural theorist Maddalena Fragnito implores her 'dearest ones' to break the silence that defined 2024, 'to feel alive and to make ourselves feel heard again'. The text was originally published on effimera.org. It is translated from Italian by Sarah Barberis.

Every now and then, language dies.

It is dying now.

Who is alive to speak about it?

– Fady Joudah, 2024 1

I’ve taken my time before writing this letter, which I’m sending today to my dearest ones as a wish for a year of collective liberation. It was 'too soon' a year ago - so they said - but now it’s too late. Too late to break the silence on Gaza’s destruction, and too late to pretend that Palestine can be wiped out from our collective memory. Our silence cannot cover up the past year: silence is the name of the year 2024, and the year stands as a testament to a world that chose to look away from a genocide aired in real time. The most brutal, relativised, and well-funded genocide, supported by Western governments and others. Those who sought to stop it through international law faced harsh and disgraceful condemnation, while the perpetrators were, and continue to be, shielded, supported, and justified.

Sooner or later, we will discuss this, when words regain their power and silence becomes unbearable, even for those who remain silent. We will talk about what we saw and what we chose not to say. We will reflect on how discourse was not just limited by the threats over our every word, but how there are no words to adequately express what is unfolding. How do you express 'horror' when words no longer shake you to the core? Another newborn dies of cold in the quiet of Christmas, his sister missing her legs, his brother destroyed by a drone made in our universities, his mother lost in childbirth, and his father killed months ago. No further words are needed.

We will talk about how history records even silence, because the support for the destruction of an entire population will leave an indelible mark. We will reflect on how we were all aware we were witnessing a catastrophic moment in modern history, with profound moral, political, and social consequences, both now and in the future. But eventually, words will reveal how the language to describe it seemed somehow lifeless. A death imposed by the forced use of vocabulary and prescriptive grammar: what can and cannot be said is a result of the repression by complicit governments and by our own actions. Thus, language also died by suicide, stifled by everything we didn’t say while turning away from the destruction of a territory, its history, its homes, its infrastructure, its roads, and its people. Have we even acknowledged the most brutal extermination of journalists in history? Or the trucks of sandbags used to starve two million people? Have we mentioned that no independent international journalist has yet entered Gaza? Or the ambulances that explode like popcorn? Schools, universities, cultural centers: nothing is left. Did we acknowledge it, or did we avoid it to spare ourselves from confronting the most contradictory aspects of our present?

We were labelled anti-Semitic, dismissed, ostracised, removed from our roles, stripped of income; we lost friends, faced assaults, lost awards and grants, were excluded from conferences, investigated by police, and sometimes summoned to court. Yet, we too shaped the boundaries of our thinking, constructing silence with our own tongues, drawing both imaginary and real lines between what is acceptable to say and what is not. This, too, we will address - the fear that is human, and the cowardice. How we absorbed the law of silence while resisting the power of the strong. A surveillance of language, which is also a surveillance of thought, perpetuated by those who accused and defamed the ones who broke the silence. Those who kept calling for a debate on words, using language to uphold speech, inside-out, outside-in, clapping our lips to make the world more understandable, driven by the need for a shared memory, to prevent death by silence.

And while it's clear how such a collapse of language demands collective reflection, Dr Hussam Abu Safiya walks resolutely towards the end, clad in his white coat. The year 2024 ends with this image that speaks all the words we lacked the courage to utter together. The silence that allowed yet another Israeli assault on Gaza’s health infrastructure - perhaps its last hospital - echoes in the pixelated grains of this image. Dr Hussam Abu Safiya moves through the rubble, like Handala, the crumpled child by Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali, and like Handala, he heads towards a horizon we can no longer clearly see - will these ruins be ours? As we cultivate silence in the name of 'morality,' the inevitability of 'collateral damage,' the set tables, the 'right to self-defence,' the liberal etiquette, the 'democratic' and revisionist decency. While we linger in this polite silence, it quietly erases each one of us, forcing us to the insignificance of 'common sense.' We will speak of this eventually, when words find their strength again: about how we succumbed to the ethics of 'moderation' and the seductive complicity of 'calm,' about what remains of thought when language collapses, about what remains of the world when we confine speech.

Dr Hussam Abu Safiya walking away through our rubble is the last image of a year that will never be forgotten. A year in which a population, besieged for decades, confronted the world with the courage ignited by the desire for liberation, a way of life we have unlearned but can reclaim through words - our words - to assert that it is neither 'difficult' nor 'complicated.' Genocide is genocide, ecocide is genocide, colonial occupation is genocide, the destruction of social infrastructure is genocide, preventing a group’s reproduction is genocide, silencing all criticism by accusing it of 'terrorism' is genocide, the impunity Israel has enjoyed since 1948 is another form of genocide. The extermination of Jews was genocide, as was that of the Herero, the Kurds, the Armenians. From Turtle Island to Rwanda, genocides have persisted without end. One genocide does not negate another: it is always pronounced 'genocide' and read as a scream against the horror of death by the greed of certain humans.

Those who renounce language, therefore, both kill and die, because silence is a weapon difficult to master. Silence offers no protection, nor does it make our lives any less fragile or fragmented. Thus, these are some of the words we will speak in the coming year, to revive ourselves and feel truly alive together; to pose the questions that matter to us, those that challenge first our very existence. What life is there without language? For whom and for what do we toil in silence? Is it worth navigating spaces and times where speaking is forbidden? To live again, for those of us who can afford it, means rejecting 'common sense' and the privilege of remaining politely silent, choosing instead to voice these words out loud as an essential act. To feel alive once more, and to make ourselves heard again.

Related activities

-

–MACBA

The Open Kitchen. The fermented seed, colonialism and extractivism

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty.

-

MACBA

The Kitchen: Workshop by Marina Monsonís

The Kitchen is a meeting place open to the participation of all, especially people and organizations that want to share their knowledge and experiences around the kitchen.

-

8 Sep 2023 –31 Dec MSN WarsawMulticultural Youth Center

The Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, together with the confederation of museums L'Internationale, is establishing a Multicultural Youth Center. This is a unique space for 16-24 year olds to explore and develop their creativity, make new friends and hang out in a friendly and supportive environment.

-

12 Apr 2023 –14 Apr MACBAWhere are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

2023 – 2024 MACBAMobile Garden. A Place to Meet

An open space, a social space. How could the Museum be more open to the needs of the neighbourhood?

-

2023 – 2024 Museo Reina SofiaSchool of Commoning Practices

This exchange programme gathers different schools organized by volunteers and migrant communities in Athens (Open School for Migrants) and Madrid (School of Rights, Escuela de Español and Situated mediation School) in order to share their knowledge, exchange strategies and reflect on the experience of working together with migrant communities.

-

1 Sep 2023 –30 Jun 2024 Museo Reina SofiaTeam of Teams

This project researches citizen participation as a fundamental pillar in the creation of community.

-

1 Apr 2024 –21 Dec 2025 Museo Reina SofiaSustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

9 Dec 2023 M HKASUPERHOST | Club Antena. Intimate listening and dancing experience

with Nele Möller, Farida Amadou, Le Réalism, Céline Gillain, Roberta Miss, Elena Colombi

CLUB ANTENA is an intimate listening and dancing session with a lecture, concert, performance, catering and DJ sets, exploring what it means to listen with our bodies.

-

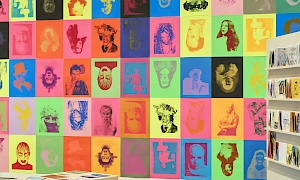

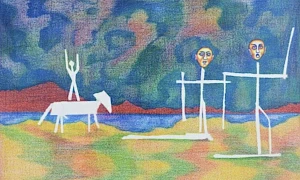

24 Jan 2024 Institute of Radical ImaginationMSU ZagrebRed, Green, Black and White

A performative inquiry by Institute of Radical Imagination and MSU Zagreb

-

2023 – 2024 Tongue and Throat Memories

On hospitality and conviviality through food

Knowledges and convenings

Cooking Sessions -

5 Jun 2024 Museo Reina SofiaPalestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

23 Oct 2024 MACBAThe Open Kitchen. Map of edible tensions

with Marina Monsonís, Paisanaje and Ruralitzem

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

11 Dec 2024 MACBAThe Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

23 Jan 2025 HDK-ValandBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

28 Jan 2025 Moderna galerijaBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

27 Nov 2024 WIELSBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

10 Oct 2025 –18 Jan 2026 Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

10 Nov 2025 –16 Nov MACBAMuseo Reina SofiaSchool of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

14 Feb 2025 –13 Apr SALTPlant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

2025 Museo Reina SofiaSchool of Commoning Practices: Publication

Students, teachers and organizations of self-managed language and cultural mediation schools for migrants in Florence, Athens and Madrid share their experiences.

-

1 Jan 2025 –31 Dec Museo Reina SofiaSustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

25 Mar 2025 NCADBook Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

8 May 2025 –9 May Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

25 Apr 2025 Museo Reina SofiaPoetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

24 Jun 2025 WIELSCollective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

8 Oct 2025 –24 Jun 2026 Museo Reina SofiaStudy Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

21 Oct 2025 –25 Oct MSU ZagrebOctober School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

3 Oct 2025 –18 Jan 2026 MSN WarsawNear East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

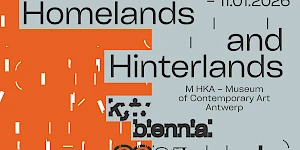

9 Oct 2025 –11 Jan 2026 M HKAHomelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

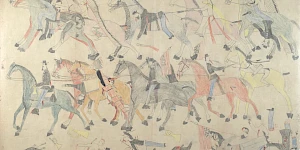

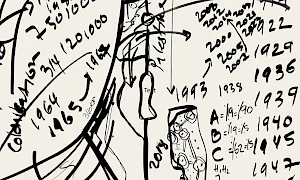

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

23 Oct 2025 HDK-ValandMA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

16 Oct 2025 MACBAPEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

23 Oct 2025 –7 Feb 2026 Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

24 Oct 2025 –28 Dec In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

15 Nov 2025 MACBASchool of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

1 Nov 2025 –28 Feb 2026 MACBAVisions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

6 Nov 2025 MACBAFarah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

5 Nov 2025 MACBAProject a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

3 Nov 2025 MACBAPalestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

31 Oct 2025 Museo Reina SofiaCinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

11 Nov 2025 –6 Jan 2026 Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

28 Nov 2025 –29 Nov International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

29 Nov 2025 –30 Nov SALTScreening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

12 Dec 2025 MACBAPEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana Piškur22 Jan 2024 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine Group12 Jan 2024 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine Group8 Dec 2023 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena Fragnito19 Apr 2024 EN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale Confederation17 Apr 2024 EN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu6 Dec 2023 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Rewinding Internationalism

2023 InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

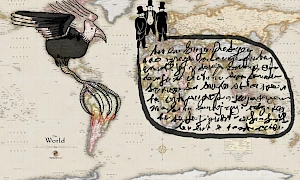

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise Vergès21 Dec 2023 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick Wilson20 Dec 2023 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Prácticas lumbung para resistir y colaborar desde el arte

Constanza Yévenes Biénzobas30 Aug 2023 EN eslumbungSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Algunos términos que guían a lumbung press: Definiendo “edición”

Erick Beltrán27 Apr 2023 EN eslumbungSituated OrganizationsMACBA -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board29 Nov 2023 EN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine Salamé23 Feb 2024 EN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana Issa4 Mar 2024 EN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary Fawzy29 Feb 2024 Land RelationsSituated Organizations -

Mix tape: Let's funk up all genders!

Materia Hache / Others to the Front19 Mar 2024 EN esSonic and Cinema CommonsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’ad27 Mar 2024 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Towards Collective Learning, or, Decompartmentalizing Education

María Berríos, Fran MM Cabeza de Vaca, Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide, Nick Aikens4 Apr 2024 SchoolsSituated Organizations -

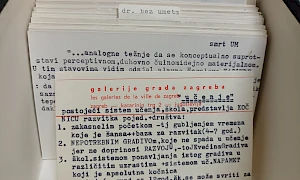

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative Croatia11 Apr 2024 InternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

Reading list: School of Common Knowledge 2024

School of Common Knowledge21 May 2024 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena Vesić14 May 2024 InternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca Popa28 May 2024 Land RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca Voinea31 May 2024 Land RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

Precolumbian13 Jun 2024 EN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Dispatch: In between the lessons. Staying together in uncertain times, laughing in the face of trouble, and disobeying; the future belongs to us

Antonela Solenički19 Jun 2024 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: The Commonsverse and Situated Organisations – or why the era of big institutions will come to an end

Denise Pollini19 Jun 2024 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: A Buriti Tree

Lucas Pretti10 Jul 2024 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Poner el nombre a una causa en tierra extraña

Dagmary Olívar Graterol, Paola de la Vega Velastegui5 Jul 2024 EN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Dispatch: To whom it may concern – the voice of the censor and re-calibrating words as an act of survival

Anonymous27 Jun 2024 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida Kovač18 Jul 2024 SchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana Anani10 Sep 2024 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay Prashad16 Oct 2024 InternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel Rahman14 Nov 2024 EN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi Yurteri15 Nov 2024 InternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

2024 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Taking Part. A Guide to Participatory Tools and Techniques

2024 EN esSchoolsSituated OrganizationsMuseo Reina Sofia -

Atención: participar en el Museo de los Comunes

Fran MM Cabeza de Vaca6 Mar 2025 EN esSchoolsSituated Organizations -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena Fragnito13 Jan 2025 EN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa Salameh20 Jan 2025 EN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-Ghoul20 Jan 2025 EN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura Adam5 Feb 2025 EN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes14 Feb 2025 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel Sniderman8 Apr 2025 EN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida Knežević31 Mar 2025 EN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna Zielińska23 Apr 2025 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader28 May 2025 EN nl frInternationalisms -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo Jee9 Jun 2025 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar Seyla18 Jun 2025 Internationalisms -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise Vergès2 Sep 2025 Internationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal Özvarış8 Sep 2025 EN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet Çelik10 Sep 2025 EN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial Board2025 Internationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem Günaydın7 Oct 2025 Internationalisms -

Statement in support of M HKA

L’Internationale Confederation9 Oct 2025 Statements and editorialsSituated Organizations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine Group27 Oct 2025 InternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura Adam3 Nov 2025 EN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October School12 Nov 2025 SchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale26 Nov 2025 EN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

The Fifth Estate: On Museums, Public Imagination and the Vanishing Space for Collectivity

Philippe Pirotte, Els Silvrants-Barclay18 Dec 2025 EN nlSituated OrganizationsM HKA -

Poetry Against Language Dioxide

Rana Issa12 Feb 2026 Internationalisms -

The Object of Value

Slinko3 Mar 2026 InternationalismsLand Relations -

Translated into Socialism: An experiment in internationalism

Merve Elveren, Tevfik Rada, Sezgin Boynik9 Mar 2026 Internationalisms