One Day, Freedom Will Be

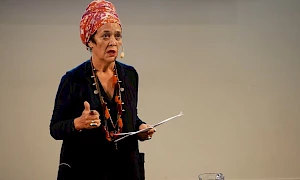

In conversation with Maddalena Fragnito and Marco Baravalle, decolonial feminist thinker Françoise Vergès charts the intersecting frameworks and rhetorics of art and its institutions, coloniality and the ongoing project of decolonization, and rapid climate breakdown. This is the first in a series of texts published in the publication Art for Radical Ecologies (manifesto) (2024).

Les enfants, mettez le feu, mettez le feu!

Mettez le feu pour mettre de l’ordre

Mettez le feu, mettez le désordre

Mettez le désordre pour mettre de l’ordre

– Pebouchfini feminist group, 20181

1. Dis-Order

Palestine is a lens through which to examine decolonization processes within Western institutions. Despite ongoing discussions about art and the decolonization of cultural and artistic institutions, these entities often struggle to address the issue’s root causes. The challenge lies in confronting the foundations of liberal democracies, such as the United States, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, which present themselves as benevolent humanitarian regimes advocating for women’s and children’s rights, freedom, and equality. Therefore, the concept of democracy is entwined with genocidal violence, land theft and object looting to populate the prestigious collections of Western museums. On the one hand, democracy is portrayed as the pinnacle of global human rights protection, justifying further exploitation of energy, land and objects. On the other hand, it is an ongoing struggle for social, gender and racial justice against imperialism and racial and patriarchal capitalism. Cultural and artistic institutions should start addressing this evident contradiction, which is intentionally avoided in the failed processes of decolonizing Western institutions.

Let’s be clear: the term ‘Western’ is frequently employed, but it requires clarification. In this context, it refers to the West constructed by colonial modernity, colonization and the establishment of racial hierarchies. This process necessitated the erasure of marginalized people, such as nomads and prisoners, along with their Indigenous communities and linguistic diversity, to build monolingual nation-states. I draw upon Cedric Robinson’s theory of Racial Capitalism to underscore the construction of racialization processes on Western soil. From this perspective, Palestine holds a crucial role as the Israeli nation-state epitomizes the systematic, murderous and brutal violence inherent in the concept of liberal-imperial democracy. This process results in a government that seizes everything: life, land, culture and memory.

Despite facing an unmistakable situation – an ongoing genocide – cultural and artistic institutions hesitate to denounce and address the core issue at hand. Instead, they adeptly conceal it due to their evident complicity with an idea of ‘democracy’ that avoids confronting its association with the colonial-racial regime. This same reason makes me doubt the feasibility of decolonizing Western cultural and artistic institutions. This scepticism does not negate ongoing struggles, such as demands for restitution, reparations, improved working conditions, an end to sexual and racial violence, and fair pay for often overlooked workers like cleaners, guards and technicians. However, I believe it is urgent and crucial to channel energy into envisioning new institutions. Nevertheless, this is no easy feat given the entrenched nature of traditional institutions over two centuries (the nineteenth and twentieth), with their profound impact, influence and power. Breaking free from the traditional institutional mindset poses a significant challenge. It is difficult to assert that these institutions are failures, especially considering the unprecedented number of people visiting museums and cultural institutions today. We cannot simply claim that these institutions ‘do not work’; they undeniably exert an attraction that merits analysis. Therefore, it becomes crucial to explore what makes them so appealing.

At the core of this fascination is the idea that these spaces represent freedom, beauty, harmony and universal dialogue more than other spaces like academia or unions. Cultural and artistic institutions are often regarded as primary arenas for freedom of thought and criticism. However, the belief that these spaces are the exclusive domains for natural critical thinking and imagination is illusory. In reality, spaces of freedom and critical thinking exist everywhere – in Indigenous struggles against land theft, among striking workers, in migrant struggles for water and within refugee camps. These spaces challenge existing norms and serve as platforms where new institutions are envisioned not as something entirely novel but as transformative processes that fundamentally reconsider the foundations of these institutions.

Therefore, while the decolonization framework has become pervasive in museums, integrated into seminars, exhibitions and meetings, activating decolonizing processes that extend beyond aesthetics to structural changes faces hesitation, incomplete implementation, or outright censorship within institutions. There is a reluctance to challenge the foundational aspects of capitalism, particularly the capitalist structure of labour and the relationship between the worker and the extraction of their labour, including the extraction of ideas and forms. Consequently, the proliferation of debates and decolonial exhibitions that do not address the material conditions of the institutional production system can be seen as another façade for extracting the labour force. After all, the machinery of production must continue to generate commodities daily.

2. De-Constructing

Art is a realm where ‘beauty’, the Western construction of beauty, is often used to justify various actions. In this context, economic corruption associated with pursuing beauty does not tend to provoke scandal. In this confusing context, artists seeking representation in collections and exhibitions, such as advocating for 50 percent representation among displayed works, can sometimes clash with denunciations of extraction – when does representation become fair, and when does it become extraction? In other words, if the desire for representation does not fuel the denunciation of extraction, there may be a need to redirect this desire toward a more fundamental desire for transformative change. Accordingly, this distinction needs clarification, which can sometimes be blurry. In fact, there is a prevailing notion that art should exist above and outside the market, but this clashes with the increasingly prevalent extraction occurring in the art world. The financialization of art warrants more vigorous denunciation or acknowledgement of what it truly is: pure financial speculation. Once again, the art market thrives on the perception of being exceptional and different from other markets, for instance, the market for commodities such as cobalt. Consequently, it does not provoke scandal as speculative activities and extractivism in the cobalt market might be. Demonstrating the extraction of ideas and artworks is not as straightforward as showcasing the extraction of resources.

Moreover, the collaboration with these institutions often stems from the precarious conditions in which artists find themselves and the illusion that museums represent a unique community. Nevertheless, despite the precarious nature of the art sector, artists harbour a strong desire to be accepted and integrated into these institutions. Consequently, a significant movement for the decolonization of cultural and artistic institutions in western Europe, extending beyond calls for increased representation, has to materialize. From this perspective, a crucial practice is exemplified by Decolonize This Place, which involves occupying museums to expose their complicity with colonial history, the arms industry, or the occupation of Palestine. This approach distinguishes itself from efforts merely seeking representation. Instead, it sheds light on the foundational aspects of museum institutions. The act of occupying museums, as exemplified by Decolonize This Place, should be replicated and evolve into a broader movement.

3. In-Visibility

The process of decolonizing artistic institutions necessitates an examination of their structural and material conditions. Where is the institution situated, and in which neighbourhood? The reasons behind its location and the architecture – whether a modern building or a palace – all play a role. Accessibility is another crucial factor. Who comprises the institution’s workforce, and under what conditions do they work? Understanding gender dynamics and racial division of labour within art institutions is essential.

Considering all these aspects beyond the cultural and artistic program is crucial. For instance, knowing the individuals responsible for cleaning the spaces and the kitchen is as important as understanding what is taught and by whom. Questioning the disparity in salaries between curators and cleaners is essential – why should curators earn more? Acknowledging that without cleaners, there would be no curation nor curator activity, challenges the conventional equation. Within this framework, exploring the social value of labour becomes imperative. Examining the economy generated by cultural and artistic institutions breaking free from patriarchal and colonial exploitation is essential. From a materialistic standpoint, it is crucial to delve into how these institutions would function and the financial resources they would require.

If we do not start from these foundational questions but only focus on programming, the undertaken process can result in something akin to pink or black ‘quotas’. On the other hand, by starting with these questions encouraging imagining anew, we may paradoxically discover that certain elements from ‘old’ institutions could still be valuable. The crucial aspect is envisioning something from scratch, starting with foundations that do not yet exist – a process we must embark upon collectively. However, as previously mentioned, this process is challenging because we are not accustomed to imagining. In other words, we struggle to detach ourselves from the existing models. While we can criticize traditional models, the courage to experiment with the unknown is required for imagining and building a decolonial institution. Thus, we need to retrain our imagination by learning to observe not just designated cultural and art spaces but also those less scrutinized – other institutions and diverse spaces, such as marginal schools and dreams. Amílcar Cabral provides an interesting example in this context, emphasizing pedagogy as a process of liberation and decolonization. Unfortunately, much of the work he did in Guinea-Bissau is largely forgotten. The desire to learn from the marginalized and the ignored must be rediscovered. Indeed, a decolonial institution is a collective experiment in knowledge, doing things differently and reshaping our learning and educational paths. For this reason, a decolonial institution can be rightfully defined not just as cultural and artistic but as social.

Moreover, decolonial and social institutions should pay attention to global events, such as the rise of fascist movements, climate disasters and how neoliberalism and authoritarianism shape an increasingly uninhabitable world for billions. Therefore, the main characteristics of a decolonial institution involve a complex exercise of imagination – one of the most urgent tasks in our current reality.

4. Un-Liveable

Every struggle concerning land, water, food, air, and the right to inhabit is inherently revolutionary. It fundamentally opposes the technological ‘solutionism’ employed by green capitalism to define and address the climate disaster. For instance, discussing the right to clean water shows how many people have already lost this essential, vital right for survival. It is no coincidence that the first thing the State of Israel did was to cut off water to Gaza and deprive the Palestinians in the West Bank of water resources for years. Historically, water has been used as a weapon of war, rewarding victors and punishing the defeated.

During colonial periods and wars, military occupation was intricately linked to the weaponization, theft and privatization of water, like the exploitative practices in plantations during slavery (where in Haiti, for instance, sugar cane, coffee and cotton required a lot of water, and incredible infrastructures were built to plunder water from the river and direct it to the plantations). Water, like land and air, has always been a critical resource, gaining significance, especially in a world where it is increasingly privatized. The issue of the climate disaster brings us back to central themes that have sparked revolts, insurrections, and revolutions throughout history – struggles for habitable land, clean water and fresh air. These struggles have always meant, and increasingly mean, dealing with the conditions of life itself – in other words, the very possibility of life. Without these essential elements, there is no human life, and much of nonhuman life would not survive either.

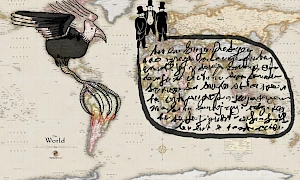

Fighting against the conditions of the climate disaster stands at the core of twenty-first-century decolonizing movements. This centrality is evident in the struggles of Indigenous peoples for land and migrants for freedom of movement. Although coloniality has evolved since the nineteenth century, its afterlives persist, manifesting in the lack of breathable air and clean water and in the erosion of resources that render parts of the world uninhabitable. In the current era of racist, patriarchal neoliberal capitalism, colonization employs both traditional and sophisticated weapons – laws, guns, contamination, genocides and massacres, alongside advanced tools like artificial intelligence, techno-nationalism and far-right ideologies. New technologies have amplified and disseminated these ideologies, contributing to the resurgence of fascist virilism.

This resurgence reflects the fear generated by the growing power of Indigenous, anti-racist, and transfeminist movements. I see these movements promising the present and future for life for human and nonhuman species that do not need to embrace posthumanism. Indeed, while posthumanism questions the white, imperialist, masculinist version of the human, the constitution of the category of the human itself, and the human/nonhuman separation; and while it looks at hybrid formations and the liberatory potential of bioengineered mechanistic futures, it has limitations. Posthumanism entered the debate as an academic conversation that ignored how Indigenous communities and non-Western theories long challenged human/nonhuman separation. Additionally, it inadequately addresses the dismantling of the racial patriarchal capitalist economy of extraction, dispossession and exploitation and the abolition of the afterlives of slavery and colonization. In contrast, abolition theory appears to offer more comprehensive possibilities.

5. Pragmatic Utopias

The invention of a division between lives that matter (humans and nonhumans) has created a dystopic world for most lives. Since the fifteenth century, colonization has introduced a dystopian temporality. For those who have benefited from this dystopia, it becomes easy to underestimate utopia as a horizon. What is termed as utopia by some is indeed their dystopia. In Western literature, emancipatory utopias often end badly, reinforcing the belief that ‘human nature’ poses a natural obstacle to peaceful coexistence and that violence is unavoidable and uncontrollable.

Despite this narrative, emancipatory utopias have frequently inspired practices of solidarity. Instances of solidarity have always existed, even within Fortress Europe, where aiding migrants is criminalized. People reject becoming agents of dehumanization and criminalization and, despite facing challenges, extend basic but vital help: a glass of water, a roof, a lift, a bed, without expecting anything in return. This solidarity challenges the state and market’s narrative of ‘protection’ and redefines it as radical care, requiring contact, shared existence and a political community. It opposes egotistic individualism, revealing our vulnerabilities and interdependencies. We are not alone; we need each other.

In our discussions on decolonization and emancipation, we often consider ourselves as if we were born already adults, young, valid and in good health. Yet, we were all born as babies and children; we will all age and may be deemed ‘non-valid’. In other words, we are more vulnerable than when we conceive what liberation is. Recognizing this exposure changes how we think about radical care and the possibility of building emancipatory utopias. The fragility and vulnerability of a child, the need for physical care in the sense of touch and recognition, as the requirements of elderly or sick individuals – all emphasize our shared fragility: vulnerability in the sense of being free together.

From this perspective, emancipatory utopias dare to think that the world, the world in which we live, must end, which is not the same thing as saying the ‘end of the world’. This is not meant in an apocalyptic sense, but to pave the way to build a future that allows us to imagine that we will all be free one day. Not all ends of the world are tragic, as Robyn Maynard said. The end of this world can be a non-apocalyptic moment. The struggle will be long and complex but also filled with joy. It took four centuries to abolish the criminal system of colonial slavery, yet the enslaved never ceased fighting for the emancipatory utopia, claiming: ‘One day, we will be free.’ Yes, one day, we will be free! One day, there will be freedom for all.

For me, the future holds the promise that one day, this world will cease to exist. It must cease to exist.

References

Amílcar Cabral, Politics and Culture in African Emancipatory Thought, Québec: Daraja Press, 2021.

Robyn Maynard and Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Rehearsals for Living, Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2022.

Cedric J. Robinson, On Racial Capitalism, Black Internationalism, and Cultures of Resistance, London: Pluto Press, 2019.

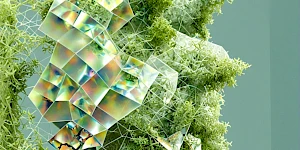

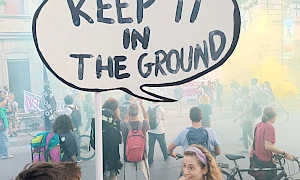

Image from homepage: courtesy of Emanuele Braga

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

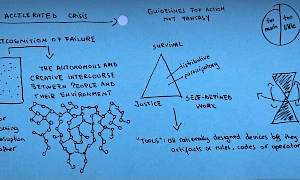

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

Institute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb

Red, Green, Black and White

A performative inquiry by Institute of Radical Imagination and MSU Zagreb

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

–

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

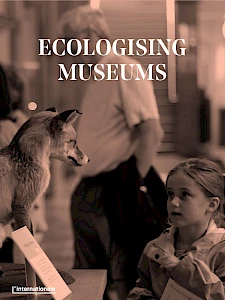

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

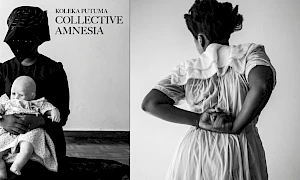

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations