‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

The following conversation took place between Ecuadorian artist Rosa Jijón and Italian Ecuadorian activist Francesco Martone, founders in 2016 of the artistic platform Arts for the Commons (A4C). Currently, the collective – also a member of the Art For Radical Ecologies platform initiated by the Institute of Radical Imagination – is focusing its work on critiques of the Anthropocene, Rights of Nature, and resistance to extractivism, in collaboration with various movements in Latin America. Sofía Acosta Varea is a Mexico-based artist and activist on Indigenous rights and against extractivism; Boloh Miranda Izquierdo is a video-maker and artist working with Indigenous communities and movements in the Ecuadorian Amazon, and Anamaría Garzón is a curator and art historian who works at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito and is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Essex, UK. The conversation is part of the publication Art for Radical Ecologies (Manifesto).

Arts for the Commons (A4C): We would like to start this four-way conversation on artistic practices and activism in Latin America by quoting Uruguayan artist and educator Luis Camnitzer, who in a recent article delved into the relationship between art and politics:

If you want it to be art, it has to have a plus. When you dedicate yourself to serve a cause, you are leaving the plus aside. There is a lot of political art that ignores the plus and then, for me, it is no longer art, it can be effective as propaganda, pamphlet or expression of my opinion, but in reality nobody cares, or nobody should care.1

As a collective, we attempted to offer a partial overview of some Latin American artists’ practices on issues related to struggles against extractivism, territorial ecofeminisms, Rights of Nature and Indigenous cosmologies in an article published in Radical History Review,2 and in an interview with Bolivian activist and practitioner José Carlos Solón, published on The Abusable Past.3 Our continent, with its vibrant social, Indigenous and environmental justice movements, and innovative approaches such as Buen Vivir (Good Living) and Rights of Mother Earth, now represents an exciting and challenging space of experimentation and convergence between cultural and visual practices and grassroots movements.4 As Latin American artists and curators from Ecuador – you, Sofía, are currently living in Mexico; Boloh in Quito; and you, Anamaría, in New York – can you explain how your work relates to ecological struggles and territorial resistance?

Boloh Miranda: When I was part of an anti-mining collective, I had a first encounter with extractivism and the violence that exists in Amazonian territories. Since then, I developed an artistic practice based on social struggles and defence of the territory, whereas nature and underlying concepts are considered in non-Western ways and in connection with social movements.

Anamaría Garzón: My practice as a historian and curator is related to issues of environment and climate justice in various manners, one of which is Art + Activisms, a laboratory of pedagogies that I co-direct with Giuliana Zambrano, at the Universidad San Francisco de Quito. Sofía is also one of the founders of the project. A+A is an annual event that, since 2018, convenes Latin American creators to discuss issues like the right to migrate, ways of being in the present, the power of translation. In addition to inviting colleagues to give lectures, we are interested in creating toolboxes, so that our students and other creators have more methodological resources to do their work. For this purpose, we had sessions on critical cartographies and creative expeditions.

Sofía Acosta: I imagine the relationship between art and activism as a liminal space, a ravine, where I have to be careful that if I go one way I’m going to fall and if I go the other way I’m going to fall… Being on that tightrope is the objective, that opens up many possibilities. For example, the work I am doing on the right to air arises from very concrete practices of installing a radio in the Ecuadorian Amazon. My initial intention, however, was to make a radio to communicate with my son, which then morphed into a very political proposal meant to think of other ways to communicate and reduce the distance. Then I asked myself how these two aspects come together. This is how the idea of installing VHS radios powered by solar panels for Indigenous communities in the Ecuadorian Amazon came up in collaboration with Rhizomatica. To me, art and activism are parallel paths, but different. When I do an artistic project I am generating many more questions, but when I work as an activist the intention is rather to offer concrete answers. However, there are times when the two lines meet. One is the line of extractivism and the defence of the territory, and the other is that of the body as a territory (or, as we say here, cuerpo-territorio).5

A4C: Sofía, readers of this essay might not be familiar with the concept of the body-territory, embodied in what Argentinian sociologist Maristella Svampa named ‘territorial ecofeminisms’.6 Could you elaborate in a little more detail?

SA: Just as another Argentinian feminist activist and scholar, Rita Segato, says, it is very important to understand how you inhabit the body from being territory and how to be territory at the same time. A project we did with Boloh during the UN Habitat III Conference in Quito came to my mind, when we gave some workshops for the counter-march organized by movements. Many women came from the Cordillera del Cóndor,7 a territory in resistance against mining, and one of them, and her women’s collective, created a piece of art in the form of a sleeping mountain-woman saying ‘we need to rest’. They went on to say:

What happens is that we cannot rest because the mountain is not resting either. Since they arrived for the exploitation of the mine, we are not resting, the mountain is not resting, and the mountain is us too. There is a relationship between the mountain and us that is not leaving us, the mine works twenty-four hours and what we want is for that woman to rest.

For me it was important to think about how to relate to the other, not only the human, but also the nonhuman.

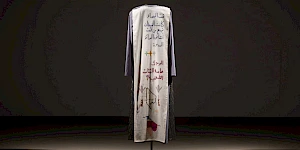

All images, video stills, A4C, Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone, #Quitosinminería, 2021, 7 min.

A4C: This helps us to understand more about the relationship of communities with their places of origin, territories to be understood in a much broader way. In Ecuador and Latin America, we understand that there is more than a universe, notably a pluriverse, a concept that helps in reconciling culture and nature, thereby ‘fixing’ the epistemic fracture represented by modernity. Our alternative is based on sentipensar (or ‘feeling-thinking’), notably the construction of affections between humans and nonhumans.8 The hierarchy of the visual was also imposed as a colonial project, discrediting the other senses and the capacity to put us in the space of affection. How do you think Latin American art relates to the polycrisis characterized by new forms of broader and more aggressive extractivism?

BM: The biggest challenge in dealing with territories and extractivism is not to fall into extractive modes, which can also result from art-making. My work is linked to struggles and people from the territories. This does not give me the right to speak on their behalf, but this does not mean that I refrain from talking about these issues. You need to be careful about where you speak from. I find it extremely challenging to translate these issues through my works when they should rather be spoken by voices from Indigenous communities and their leaders.

SA: Younger generation artists indeed show great interest in issues related to extractivism. However, they are also talking a lot about more personal crises resulting from environmental destruction, the polycrisis that you refer to, and that lead to the creation of works that are very existential. This is also the result of the pandemic. However, on the issue of extractivism there are several collectives of younger generations of artists (under twenty-five), which I find amazing and that I support and accompany at times. A Colombian artist that I admire a lot, Carolina Caycedo,9 once said that artists are not the ones who are in the front line but the ones who can be right behind, supporting that frontline so that it walks stronger. I agree with her.

A4C: The work that you, Sofía, and Boloh did on the Indigenous guard in the Amazon comes to mind. The polycrisis is not exclusively happening in rural territories, but encompasses a wider debate on the relationship between the human and nonhuman, between people’s rights and the Rights of Nature.10 When shifted on the theoretical level and hence detached from embodied conflicts and struggles, this attempt to solve the historical rupture between nature and culture risks being co-opted or used as a form of ‘greenwashing’.

SA: Several issues end up being co-opted. Some of those words can be found in artists’ statements, and works that are just destined for commercial spaces and not meant to generate questions or challenges. Myself, I always embark on self-criticism about where I am speaking from: Who am I to say this or that? Who am I to work on these issues? Self-criticism is crucial for an artist, also to prevent contradictions. This is the approach I followed in the work I did with Boloh and Nixon Andy, and with Tawna,11 a collective active on territorial issues. At that time I was also working on the radio, and on issues of activism and archiving, from the land, the soil, the minerals, the water. Both of us never thought that air is also a space of power that is being controlled and has hence become a space of surveillance.

BM: The work we did on the Indigenous Guard, together with Sofia and Nixon Andy, who is part of the Indigenous Guard of Sinangoe,12 contributed to a victory for Indigenous peoples whose rights to land, territories and resources were eventually recognized. This result was obtained thanks to the Amazon archive, the work of the Indigenous Guard and the use of camera traps and drones. The latter were used to take footage of invasions by illegal miners. We facilitate radio communication, through antennas, and a security system for communities. In parallel we explore new monitoring and communication systems adopted by the Indigenous Guard to protect their territories. A product of this participatory work is a two-channel video installation portraying a portrait of the Guard, a single body and the relationship with the territory.

All images, video stills, Frecuencia Sinangoe, two-channel video, 32 minutes, 2022. Co-directed with Sofia Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda and Nixon Andy

A4C: When commenting on your challenges in working in the rainforest with its communities, you, Sofía, said that you could not walk like them because they are jungle, and that while you had to ‘go to the jungle’, they ‘are jungle’.13 Somehow this recalls what Arturo Escobar says, that sentipensar with the territory implies thinking from the heart and mind, or co-reasoning. In a talk with Peruvian anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena on pluriversal contact zones,14 Escobar points to the key role of art in helping the dialogue with and communication of the different worlds that populate these contact zones, and also summarizes some leading concepts that emerge in these spaces, namely: territoriality, communality, autonomy and production of the commons, politics in the feminine and transition. How do these elaborations resonate in your work?

SA: An episode comes to my mind when I was in the forest with some Indigenous people and I commented, ‘this part of the landscape is so beautiful!’, and they commented, ‘no, the landscape is extractivist!’ And for me it was illuminating to see how the landscape can also be consumed, extracted, and how to get out of that notion towards something more integral, which also remains at a level of abstraction, which cannot be translated into a work of art, but remains as an experience of that specific moment. This also challenges us to think about other temporalities of being and not staying in the linear logic of production.

BM: In my experience of working with different cultures and nationalities in the Amazon, I realized that their relationship of feeling and thinking is not with nature, but of them as part of nature. I can’t understand it intellectually, but I can understand it personally, since I live with them and have experienced what it feels to be with the forest, with the jungle. When we do our work as Tawna we always put the perspective and voice of the communities and their needs and asks in the forefront.

AG: My academic work is characterized by the history of extractivism and the persistence of the colonial in the artistic narratives of the twentieth century. The history of artistic modernity tends to omit the resources on which production is based. In my doctoral work I intersect the territory, the praxis, the discourse of modernity, but also point to the separation between popular arts and modern art, that is, between Indigenous creators and white/mestizo creators. I am interested in talking about race, class and resources, to complexify the vision of the artistic.

A4C: Let’s now elaborate on the subject of disobedience in the archive, as a decolonial practice, because the archive imposes on us a past order in which we no longer have any incidence, and imposes this on us as the construction of a future that does not yet exist. The Amazon Archive you have worked on with other artists and curators,15 as well as environmental organizations, is constructed, similarly to the Tawna project,16 from a dimension that is rarely considered in symbolic production, that of desire, of the emotion of the space.

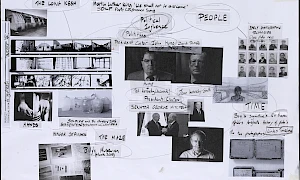

BM: The Tawna project began four years ago, in Zápara territory. We needed to take images and narratives of the territory and for that purpose we engaged Indigenous people, not only Zápara, and also non-Indigenous participants. Tawna is a collective in permanent transformation, where we question our practices, forms of creation and narrative, and our own works. We enjoy our work and our sense of belonging. We have created a very extensive archive of the Amazon with materials that are in private collections and therefore inaccessible to the communities. We collected them to take them back to communities so that their families can see themselves in past times. We have produced Allpamanda (2022), a documentary about the historical memory of seven case studies of successful struggles in the Amazon, and the Indigenous march of 1992, when several communities in the Amazon managed to reclaim their land rights. We have also digitized archives that otherwise would have been lost, with the aim of inspiring others to understand the importance of archives in social struggles, to remember history, to talk about past processes, about how stories are repeated, in order to learn from them.

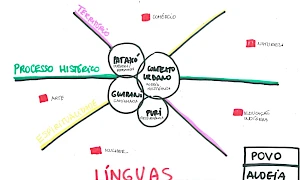

All images, Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone, A4C, FOSIL-E, contribution to the Ecuadorian publication Estado fósil, Sofía Acosta Varea, Anamaría Garzón Mantilla , Francisco Hurtado Caicedo (eds.), Terminal Ediciones, 2023

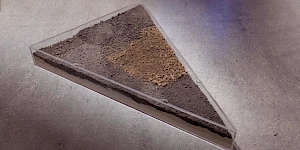

AG: In recent years nature has acquired an important place in the artistic practice of Ecuador, I think, for example in the work of listening and singing with rivers by Christian Proaño, or Estado Fósil, a multimedia and polyphonic editorial project, where we, together with Sofía and Francisco Hurtado, asked ourselves how oil, with its by-products, is present in our lives. It was published on the occasion of the celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the first barrel of oil that marked the beginning of large-scale oil exploitation in the Ecuadorian Amazon. In Estado Fósil we gathered archives and made a timeline on the history of extractivism in the country,17 but also commissioned artworks, a podcast and essays from artists, writers and historians. We wanted to make a book about the lives of our generation in relation to oil from different perspectives; we don’t know how the country was before it and exploitation traverses different layers of our communal lives. By exploring oil materialities, conflicts and imaginaries, while also recognizing its devastating damage for communities in the Amazonia, we aimed to open a conversation that involves different perspectives and relations.

SA: I am very interested in the subject of the historical archive. At the beginning I thought that history should be with a capital ‘H’ and respected the archive as such. Over time I asked myself how art and artistic research could break the narrative of the archive as reconstruction of official historical memory, focusing rather on those collective stories that remain on the margins. The Amazon Visual Archive is a project that I collaborated with when I was thinking of making a board game interpreted as an archive. The idea was that everything would self-destruct, and that it would not be possible to extract oil from the inside. I started by editing all my mother’s personal, affective archives as a long-time environmental activist. I found it incredibly attractive to edit the oil stains, those stains falling down the green mountain, that more opaque part that entered through the earth and how those textures, those chromatics, were seen. In my dreams I had nightmares where oil was being rubbed on my chest and at the end I thought that I could not stay alone with those nightmares. That’s how the idea of Estado Fósil came up as a way to socialize and expand this personal experience, so that it is not only me that questions the oil ‘era’ but also other people with different views, that other possible worlds could be represented.

A4C: Estado Fósil, to which we also contributed interviews with anti-oil activists and artists in southern Italy, is not a book or an editorial project but more an assembly of points of view, a kind of very transversal dialogue that led to producing this project in a very fluid way. It is an assembly of opinions and visions, of images of what has happened to us since the first barrel of oil. It is like a collective and there is an evident artistic methodology that you put in place. How do you relate to this methodology that went beyond calling for contributions for a publication?

SA: The idea behind the project is to create a joint vision between three very different points of view, that of Francisco ‘Pancho’ Hurtado, a lawyer who has worked for many years on human rights issues, Anamaría, a curator-academic in her forms and references, and myself. Me and Anamaría had a common language; it was challenging to find common ground with Francisco Hurtado, even if we met a lot in the field of activism, for instance with a collective called Minka Urbana on the theme of the anti-mining resistance in Nankintz.18 Estado Fósil was not just an editorial project but something that overflowed from it, and that generated other conversations. I like this project of thinking in collective conversations, not just thinking about myself. That’s why I initially thought of a board game, because playing collective archives is a way of thinking in conversation, of putting the cards on the table and saying, ‘What is this for you?’ The description that you have of an archive is enclosed beneath it – a book or an image tells you a lot of things. They are determining subjectivities that can be very colonial. The challenge is to dismantle a caption of a photo that has a [certain] look and to disarticulate it, as in a book that describes oil in an almost pornographic way, that has a much more aesthetic image and dimension.

BM: In Estado Fósil we contributed with some photos and archival material from Tawna, and also produced a text and an archive on the Texaco case, with files on spills and fires in the Amazon. We have been working with Sofía for a long time, starting with an urban art collective called Fenómeno, with graphics, painting, storytelling, with collectives like Yasunidos,19 and did some murals with them. My work on José Tendetza, ‘JOSÉ Territorio y memoria’,20 stems from my direct relationship with people who knew him when he was murdered and also with the lawyers who handled the case. It was an event that affected me personally and from there arose the need to speak, because I believe that these state crimes are easily forgotten. I used several videos, not just those produced by the community. The important thing was to show that nothing has happened this far with the case, who José was and the imposition of the mining company on the bodies that inhabit the jungle, and all the extractivist violence that open-pit mining represents. It is also a work of collecting archival and visual material on company workers, trying to recover their viewpoint. There are drone videos of Chinese workers, cell-phone images of machinery operators, and material from TikTok or other social media. The work depicts what happens in the Condor Mirador mine, the destruction, the enormous holes and the accidents suffered by workers. Likewise, I gave importance to José’s legal file and the manipulation of related evidence.

A4C: Sofía, situating the debate about the collapse and the end of the world in the place where you are now, Mexico, the words of Viveiros de Castro and Danowski about the Mayas and the end of the world come to mind.21 In the North, the concept of catastrophe, of extinction, of fear of the end, seems to permeate artistic production, perhaps excessively. What we are actually assisting is the end of the world of white people and the real challenge is to learn, as Anna Tsing put it, how to live on a damaged planet. In a continent like Abya Yala, that already experienced its end of the world with the conquest, how can we represent this lack of fear of the end of the world, if not the capacity to prefigure new possible worlds, in artistic practice?

SA: Donna Haraway says that we have to continue with the problem, and that is true. There are many artists who got into that line of ‘What can we do in this catastrophic world?’, something that is very much felt in the North, while in the South we are experiencing other possibilities of building other possible worlds. Paraphrasing Bolivian feminist and decolonial thinker Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, in this chaos there are threads that intertwine. Where we have a wave of catastrophe, we also have many resistances and ways of thinking about the world from other places, like with the Zapatistas.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

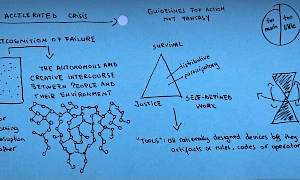

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

Institute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb

Red, Green, Black and White

A performative inquiry by Institute of Radical Imagination and MSU Zagreb

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

Related contributions and publications

-

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

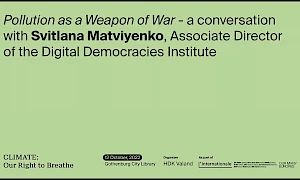

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

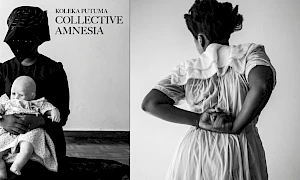

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations