Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

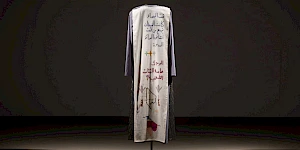

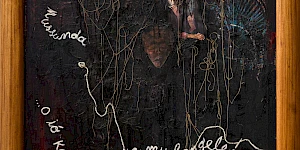

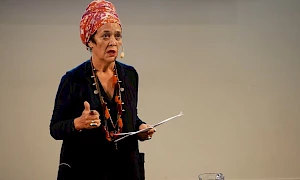

In her article, researcher Sanabel Abdel Rahman explores the genres of Magical Realism and Climate Fiction within Palestinian literature. Written within the context of the ongoing genocide in Palestine, Abdel Rahman turns to Magical Realism and Climate Fiction, what she describes as ‘kaleidoscopic literary modes, operating beyond reality – in a magical reality’ that can create ‘a dynamic and potent space in which Palestinian collective agency, imagination and future liberation can be reified’. Running through the text is a series of images by the Palestinian, self-taught painter Sager Al Qatil (1959-2004), selected by Abdel Rahman for their affinities with Magical Realsim and Climate Fiction.

In one of the most widely recognized images of Palestinian reality, 60-year-old Mahfoza Oud embraces an olive tree with her eyes closed.1 An Israeli soldier is ensconced behind her in his truck, looking down at her, his face hidden by sunglasses and a combat helmet. Mahfoza’s trees were chopped down by Israeli settlers in 2005: the Israeli practice of obliterating Palestinian presence from the land is not a new phenomenon, but under the current fully fledged genocide, carried out by Israeli soldiers and settlers in Gaza and the West Bank, violence against Palestinian nature takes on an increasingly vengeful streak. Since the genocide in Gaza started in October 2023, Israeli soldiers and settlers have been uprooting and burning Palestinians’ trees and killing their livestock with new intensity.2 The hanging of a donkey head on the fence of a Muslim cemetery in Al-Quds in December 2023 by an Israeli man is emblematic of the intensification of collective acts of violence by the Israelis against animal, as well as human, life in Palestine.3

Palestinians’ relationship to their land and to nonhuman life is diametrically opposed to such grotesque treatment. Investigating the magical-realist mode in Palestinian literature, especially in conversation with Indigenous climate fiction, offers piercing and comprehensive insights into this relationship. A study of this kind also helps us to understand Palestinians’ conceptualizations and practices of love and dedication towards the land, and their concomitant tenacity in defending it against atrocities.

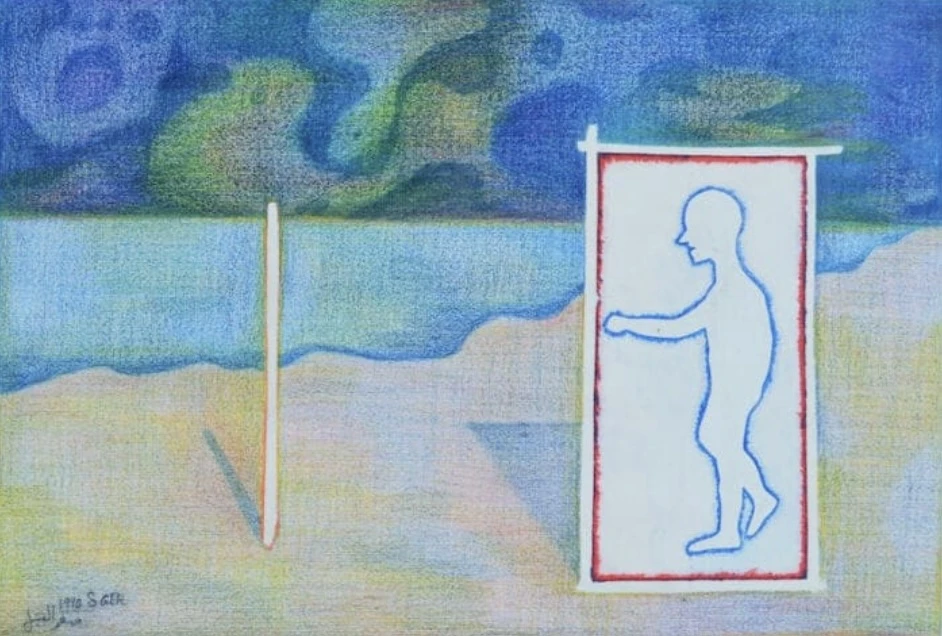

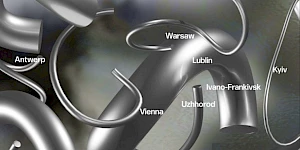

Sager Al Qatil, Untitled, 1990. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

Palestinian (Magical) Realism

First, let us consider the term ‘Palestinian realism’. As documented in several books in the field of Palestinian studies, Palestinian literature and life are often viewed through the lenses of realism or more specifically trauma.4 This literary tradition is often understood as an extension of post-1967 ‘Arabic realism’, which prevailed following the Arab–Israeli War of 1967. Palestinian commitment to realist writing took form across documentary, social and poetic realisms.

Though accurate in depicting present realities, such lenses often fail to capture the nuances and paradoxes of Palestinian life, ranging, for instance, from exile and refugee experiences to everyday life under violent settler colonialism and the phenomenon of the ‘present-absentee’ Palestinian.5 A (purely) realist view confines Palestinian agency and dreams of liberated futures within harsh realities and tropes of trauma. This, in turn, freezes Palestinians in the present and deems almost impossible their ability to comprehend the past and act with agency towards the future.

Magical realism can be mobilized to address this conundrum. As a kaleidoscopic literary mode, operating beyond reality – in a magical reality – it can play a significant role in reinstating Palestinian presence and agency. In my research, I have used magical realism as a tool to investigate settler- and post-colonial contexts. I view this tool as capable of creating a dynamic and potent space in which Palestinian collective agency, imagination and future liberation can be reified.

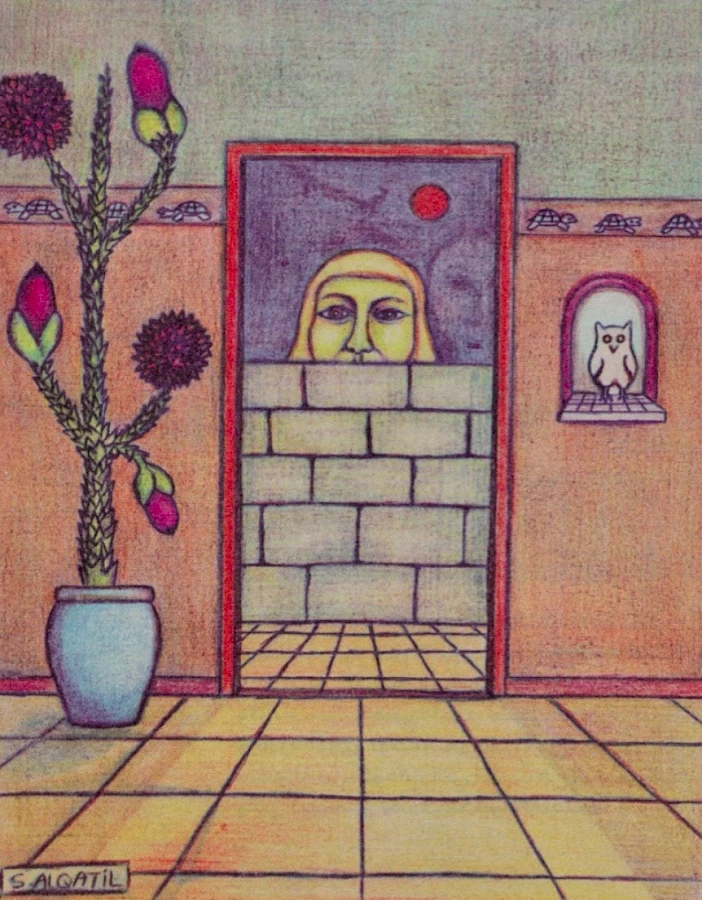

Sager Al Qatil, Untitled, 1990. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

The term ‘magical realism’ was initially coined within the visual arts in the early twentieth century and morphed to become a literary genre. It is often studied within the Latin American context, such as in the works of Gabriel García Márquez, Jorge Luis Borges and Isabel Allende. Arabic and Palestinian magical realism, however, are under-researched.

Magical realism remains an elusive term. In its broadest meaning, it is defined as ‘fiction which mixes and disrupts the ordinary, everyday realism with strange, “impossible” and miraculous episodes and powers…’.6 It is often referred to interchangeably with genres such as fantasy, speculative or science fiction, surrealism, absurdism, and the Gothic. By approaching magical realism as a hybrid literary mode, elements from these different genres can be injected into the ever-transforming frameworks and modes of ‘political realisms’.

This is especially pertinent in the Palestinian case as the Palestinian struggle for liberation is itself concerned with distorted material realities. The forms of distortion inflicted upon Palestinian realities extend beyond the physical occupation of the land, demolishment of houses, uprooting of indigenous trees, firing of rockets and destruction of material structures; they are also wrought on corporeal space, as in martyrdom, maiming, massacres, imprisonment, torture, rape and the destruction of Palestinians’ senses, such as sight and smell. They include the erasure of memory and recurrence of nightmares, as well as threats to mobility, as in refugeehood and exile. These distortions are synonymous with Israel’s systematic land grabs, ethnic cleansing, destruction of Palestinian homes and gentrification of Palestinian neighbourhoods, and the imprisonment, maiming and killing of Palestinians bodies. The ongoing genocide against Palestinians in Gaza has brought forward horrific accounts of rape, the mutilation of corpses (running over living and dead Palestinians with tanks has become a common phenomenon), and the burning of refugees in their tents. These testimonies, recounted daily in the news, underscore Israel’s desire not only to kill Palestinians, but to experiment with different forms of death, more horrific than could be imagined in even the most graphic work of fiction.

Given the seemingly paradoxical composition of magical realism, whereby the real and the magical coexist without contradiction, the mode’s base in ‘realism’ holds political and revolutionary potential. At the same time, the magical aspect buttresses this potential and accentuates the aberrant realities, which usually emanate from settler- and post-colonial contexts. Such is the case with Palestine.

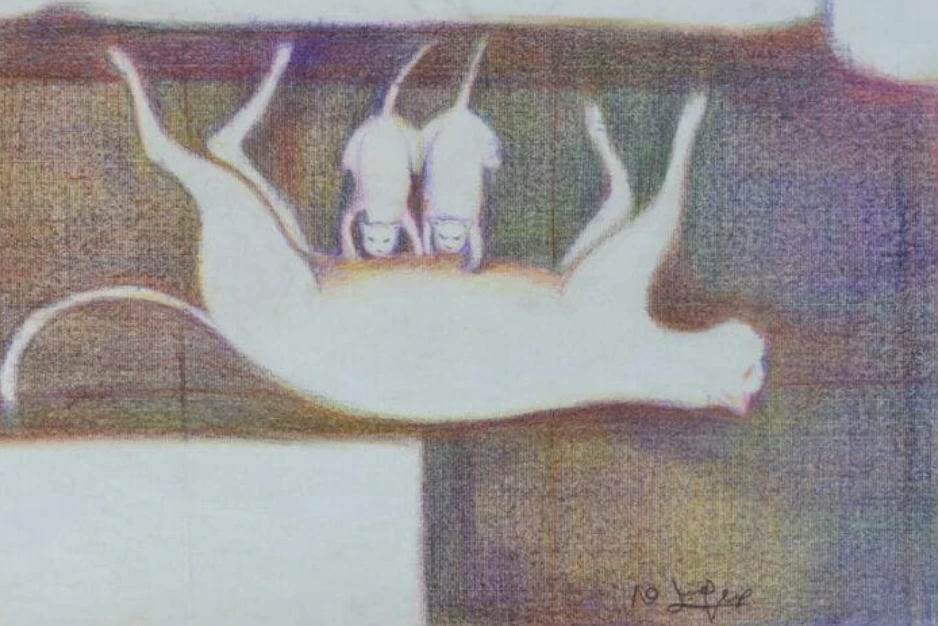

Sager Al Qatil, Untitled, 1999. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

Certain figures, tropes, transitions and transformations recur through many magical-realist texts. In the Palestinian case, these elements play pivotal roles by keeping Palestinian memory alive while foregrounding hope and agency. The power of mythical creatures, for example, transcends mortal threat from Israeli violence. We see this in ‘Saraya Bint al-Ghoul’ (retold in Emile Habiby’s 2006 novel of the same name, in English, Saraya, the Ogre’s Daughter), where the figure of farāsha (butterfly) is able to penetrate Israel’s elastic borders without being seen, and where the young mythical boy Badran, who lives inside Palestinian rocks and waters, saves Palestinians from Israeli danger when summoned.7

Ghosts and Eco-Surrealism

In relation to Palestinians’ connection to nature within the genre of magical realism, I suggest the term ‘eco-surrealism’. The term encapsulates surreal instances that reflect Palestinian connections to the land within magical-realist frameworks, and how this connection moves beyond gendered dichotomies of a man saving the female land into surrealist associations and potentialities. One such instance of eco-surrealism can be discerned in Shaykha Hlewā’s story ‘Mi’at Hikaya wa Ghaba’ (‘One Hundred Tales and a Forest’) when a young woman literally glues herself to the land and grows a blossoming branch on her shoulder.8 In the same story, a tree uproots itself and picks up the young girl to save her from a fire before returning to its roots. Hlewa’s use of eco-surrealism therefore offers the possibility for Palestinian agency amid impending disaster.

Such eco-surrealist instances in contemporary writing reflect developments and transformations in parts of Palestinian literature. They take on a special function when describing the crucial relationship between Palestinians and their land. These relationships are surrealist in that they recur in dream and nightmare spaces. Dreams and, more commonly, nightmares also constitute the surrealist streaks of magical realism. They reflect the damage inflicted on the collective psyche since the Nakba. Yet they simultaneously draw on dreams of future liberation, giving power to Palestinian steadfastness.

From Gabriel García Márquez to Toni Morrison and Mahmoud Darwish, ghosts play pivotal roles in magical realism. Palestinian ghosts, usually emerging from martyrs’ bodies, help reframe and rethink common traditional Palestinian tropes such as martyrdom and connections to the land. Ghosts usually linger in liminal or third spaces. When they emerge from the bodies of martyrs, visiting the living, they are accepted by living Palestinians as real, and sometimes even protected from the gaze of foreign voyeurs, who seek to turn Palestinian tragedies into plays, like the European characters represented in Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun.9 In addition to fuelling practices of perseverance and resistance, many Palestinian ghosts evoke guilt, such as when the ghost of the aforementioned Saraya emerges from the water to meet the narrator, who has just returned to Palestine after years of exile, and poignantly asks him: ‘Have you forgotten us?’10 Such a confrontation challenges the distortion of Palestinians’ spaces, which suffer from physical erasure as well as erasure from memory.

Further, in the essay ‘The Glossary of Haunting’ Eve Tuck and C. Ree present a glossary of lingering ghostly presences in the wake of colonization.11 Tuck and Ree begin by speculating that:

the glossary appears without its host – perhaps because it has gone missing, or it has been buried alive, or because it is still being written. Maybe I ate it… The glossary is about justice… It is about righting (and sometimes wronging) wrongs; about hauntings, mercy, monsters, generational debt, horror films, and what they might mean for understanding settler colonialism, revenge, and decolonization.12

Tuck and Ree offer definitions of terms such as ‘Agent O’, ‘Beloved’, ‘Decolonization’, ‘cyclops’, ‘monsters’ and ‘revenge’. They describe the glossary as ‘fractal; it includes the particular and the general, violating the terms of settler colonial knowledge’.13 They open the ‘A’ section with ‘American anxieties, settler colonial horrors’, explaining that ‘settler colonialism is the management of those who have been made killable, once and future ghosts – those that had been destroyed, but also those that are generated in every generation’; in short, ‘settler horror’.14 The authors explain how haunting challenges the ‘relentless remembering and reminding that will not be appeased by the settler society’s assurances of innocence and reconciliation’.15 Their argumentation is summed up in the statement ‘for ghosts, the haunting is the resolving, it is not what needs to be resolved’.16

In ‘A Glossary of Haunting’, we can observe links between the poetics and the agencies of Palestinian and Indigenous martyrdom within the magical-realist mode. Indigenous hauntology and Palestinian magical-realist martyrdom open up potent spaces for the colonized, who have been negated in both physical and metaphysical forms through settler-colonialist violence. The possibility to have agency even after their death weakens the dominance of settler colonialism and the power of the colonizers.

Sager Al Qatil, Untitled, 1999. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

This phenomenon can be discerned in Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance.17 At the end of the novel, it is implied that Palestinian ghosts return to haunt the Israeli settlers following a magical phenomenon where all Palestinians mysteriously disappear overnight. The sudden and forced disappearance of Palestinians is presented as a realization of the Israelis’ deep-seated desire for Palestinians to cease existing, a desire shared across the society. This chimes with Tuck and Ree’s assertion that ‘decolonization must mean attending to ghosts, and arresting widespread denial of the violence done to them.’18 This is echoed in Sinan Antoon’s afterword to The Book of Disappearance in which he states: ‘the ghosts of the dead will continue to haunt, demanding justice and recognition, and the living will write and remember’.19

Indigenous Climate Fiction

Indigenous climate fiction opens up generous spaces to attend to such ghosts while giving agency to the occupied lands to free themselves from settler colonialism. By remaining true to collective struggle and liberated imaginaries, Indigenous climate fiction exposes what has been concealed about violence against nature under settler colonialism. Briggetta Pierrot and Nicole Seymour unpack the topic of climate fiction within Indigenous studies in their essay ‘Contemporary Cli-Fi and Indigenous Futurisms’.20 The authors first highlight the origins of ‘climate fiction’, the name journalist Dan Bloom gave to the category of speculative fiction concerned with climate change and catastrophe, before critiquing its scope. Pierrot and Seymour’s criticisms centre on the claim that climate-fiction texts do not address how climate catastrophes are caused by settler colonialism.

Pierrot and Seymour present various approaches to the climate-fiction genre but insist that in most cases, Indigenous experiences are either absent or appropriated. When mentioned, Indigenous experiences and connections to the land are added with a heavy hand, merely to ‘provide a disembodied source of wisdom and a veneer of multiculturalism.’21 The authors note that, in advanced university courses that study climate fiction, the analyses around the works usually ‘invoke indigenous peoples only to absent and sometimes even appropriate their experiences and traditions’.22

The empiricist approach usually employed when describing climate crisis – measuring CO2 emissions, the greenhouse effect, acid rain, earthquakes, neurophysiological research, rising sea levels – although to some extent apposite, serves to negate thousands of years of lived knowledge and experience accumulated by and shared among Indigenous peoples. Rebecca Evans (cited by Pierrot and Seymour) underlines this tendency: ‘popular climate-catastrophe narratives… focus on the future of destabilization of white Western privilege rather than the environmental and climate injustices that are ongoing yet ignored in the present.’23 Pierrot and Seymour then go further to argue that ‘intentionally or not, some mainstream cli-fi functions in large part to justify settler colonialism.’24

Studies of climate fiction often neglect to mention an alarming feature of the genre, inherited from science fiction: the persistence of a single, usually white male hero, who saves the world from an impending catastrophe. Tuck and Ree make a similar observation about horror films, writing that:

mainstream narrative films in the United States, especially in horror, are preoccupied with the hero, who is perfectly innocent, but who is assaulted by monstering or haunting just the same. … The hero spends the length of the film righting the wrongs, slaying the monster, burying the undead, performing the missing rite, all as a way of containment.25

Pierrot and Seymour meanwhile introduce an important related term, coined by April Anson, ‘settler apocalypticism’. Here, ‘the “state of emergency” story serves the settler state’s white claims to the land.’26 Anna E. Younes’s eye-opening essay ‘Palestinian Zombie: Settler-Colonial Erasure and Paradigms of the Living Dead’ is insightful in this regard.27 Younes places the figure of the zombie in the Palestinian context within the frameworks of land conquest and erasure under capitalism. ‘From the 20th century onward,’ Younes writes, ‘a white (genocidal) gaze eventually turned the zombie myth into a flesh/meat-eating figure, roaming the land without direction and in need of cleansing from the earth.’28 Younes explains how this zombie figure emerges from colonialist capitalism: ‘Today, zombies represent capitalism’s surplus populations: they are passive and excluded from political projects.’29 In this reading, the ultimate zombie that must be annihilated so that the Western order can be restored is the Palestinian zombie.

In these settler-colonial narratives, it becomes one hero’s ‘mission’, perhaps even his ‘fate’ to cleanse the conquered lands from their zombie residue. Such an individualist approach within non-Indigenous climate/science fiction negates the collective work of imagining that recurs in magical realism – and specifically, eco-surrealism – with the latter mode’s emphasis on the popular, the communal, the collective and the traditional.

Folktales and Science Fiction

This solipsistic view on how to deal with a man-made colonial disaster is constantly challenged in both Palestinian folktales and contemporary literature. For example, in the folktale ‘The Louse’, an entire Palestinian village self-annihilates in an act of mourning when a flea’s husband (also a flea) falls into an oven and burns to a crisp.30 The tale begins with the flea asking her husband to bake bread, but then he falls into the oven and dies. She applies soot to her face to mourn him and goes around the village telling the river, the goat, the tree, and others what happened. In an act of collective mourning, the tree breaks its own branches, the river dries itself up, the goat makes itself limp, and so on, until the entire village makes itself disappear. The manifestation of more-than-human solidarity within Palestinian culture explored in this folktale not only insists on the need to come together as a nation, but also allows the land to have agency over its very existence and to partake actively in building communities.31 This strengthens Palestinians’ connection to places from which they were forcefully expelled and portends transgressive relationships and futures in which the liberation of the land can be conceived of and materialized.

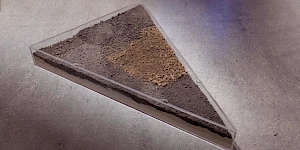

Sager Al Qatil, Tree of Life, 1999. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

The absence of spaces of agency, unity and solidarity within mainstream climate fiction underscores the need to incorporate, critically and expansively, Indigenous and native experiences, histories and associations with the land, outside of settler-colonialist and capitalist systems. How can those who have been severed from their land be welcomed back rightly to the place they inhabited for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, before these places were ‘discovered’ for their natural riches? What is climate fiction without settler-colonial and imperialist critique? How can we place Indigenous forms of knowledge of the land and about the climate under serious academic investigation?

In a conversation between the editor of the anthology Palestine + 100, Basma Ghalayini, and the cofounder of Comma Press, Ra Page, we hear similarly about the colonial origins of the science-fiction genre.32 While focusing on Palestine + 100, a collection of science-fiction stories about Palestine one hundred years after the Nakba of 1948, Ghalayini and Page highlight science fiction’s original planetary-scale wish to occupy faraway lands beyond the Earth. From this critical conversation around science fiction as a genre, it follows that climate fiction could be susceptible to falling into similar traps when it is presented or created without any critique of the conditions of settler colonialism, imperialism and capitalism, which gave – and continue to give – rise to climate catastrophes.

Similar to these Palestinian attempts to redress science-fiction tropes, Indigenous Latin American climate fiction subverts the genre. Dominican writer Rita Indiana’s novel Tentacle centres a magical sea anemone that possesses magical powers to manipulate time and make people transition across genders.33 The anemone also has the power to force humans into many kaleidoscopic material realities at once. One of the novel’s protagonists is Argenis, an artist who was pushed into a parallel reality after being stung by the creature’s tentacle. Argenis is forced to relive the city’s colonial history as a labourer for a buccaneer, while still living in the current time as a contemporary artist, thus living two lives simultaneously, in the same place but at different times.34

The sea anemone, a venomous creature, manifests the notion of nature fighting back. That, in Tentacle, the anemone has the magical powers to make human beings literally relive history, including the origins of colonization, invokes an eco-surrealist relationship between humans and nature, a relationship that has been sacrificed for settler-colonialist fantasies, which led to the very climate catastrophes of Argenis’s life in the present.

It is in this same nature (or ‘real’/material world) that the blood of Palestinian martyrs makes the anemone grow – not as in the sea creature, but the flower, a potent symbol in Palestinian culture. The way in which the anemone exists in both marine and floral forms in Indigenous Latin American and Palestinian literary works exceeds this wondrous homophonic coincidence to fatefully signify the shared histories of these cultures through connections to, love for, and loss of the land.

This essay has attempted to show how Palestinian magical realism and Indigenous (critiques of) climate fiction can enrich the ways we see and interact with the world through enshrined knowledge, experience and care for the land. Capitalism and other expansionist systems of living can never reach such goals. The generative overlap between Palestinian magical realism and Indigenous approaches to climate fiction evokes hopes of reversing the effects of climate catastrophe and gives agency and power to the Indigenous and colonized peoples who reimagine and die for the land and strive for the liberation of their peoples – from Turtle Island to Palestine.

Sager Al Qatil, Untitled, 1985. Courtesy Zawyeh Gallery

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–tranzit.ro

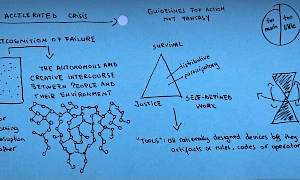

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Gothenburg

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and Mills Dray (HDK-Valand), 17h00, Glashuset

-

Moderna galerija

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Ljubljana

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Bojana Piškur (MG+MSUM) and Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU)

-

WIELS

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand), Subversive Film and Alex Reynolds, 19h00, Wiels Auditorium

-

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

NCAD

Book Launch: Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Dublin

with Nick Aikens (L'Internationale Online / HDK-Valand) and members of the L'Internationale Online editorial board: Maria Berríos, Sheena Barrett, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Sofia Dati, Sabel Gavaldon, Jasna Jaksic, Cathryn Klasto, Magda Lipska, Declan Long, Francisco Mateo Martínez Cabeza de Vaca, Bojana Piškur, Tove Posselt, Anne-Claire Schmitz, Ezgi Yurteri, Martin Pogacar, and Ovidiu Tichindeleanu, 18h00, Harry Clark Lecture Theatre, NCAD

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

WIELS

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Brussels. Rana Issa and Shayma Nader

Join us at WIELS for an evening of fiction and poetry as part of L'Internationale Online's 'Collective Study in Times of Emergency' publishing series and public programmes. The series was launched in November 2023 in the wake of the onset of the genocide in Palestine and as a means to process its implications for the cultural sphere beyond the singular statement or utterance.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

–

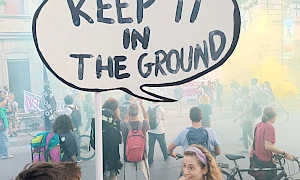

International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People: Activities

To mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People and in conjunction with our collective text, we, the cultural workers of L'Internationale have compiled a list of programmes, actions and marches taking place accross Europe. Below you will find programmes organized by partner institutions as well as activities initaited by unions and grass roots organisations which we will be joining.

This is a live document and will be updated regularly.

-

–SALT

Screening: A Bunch of Questions with No Answers

This screening is part of a series of programs and actions taking place across L’Internationale partners to mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People.

A Bunch of Questions with No Answers (2025)

Alex Reynolds, Robert Ochshorn

23 hours 10 minutes

English; Turkish subtitles -

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Rewinding Internationalism

InternationalismsVan Abbemuseum -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

Everything will stay the same if we don’t speak up

L’Internationale ConfederationEN caInternationalismsStatements and editorials -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Rethinking Comradeship from a Feminist Position

Leonida KovačSchoolsInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsMSU ZagrebModerna galerijaZRC SAZU -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Broadcast: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency (for 24 hrs/Palestine)

L’Internationale Online Editorial Board, Rana Issa, L’Internationale Confederation, Vijay PrashadInternationalismsSonic and Cinema Commons -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

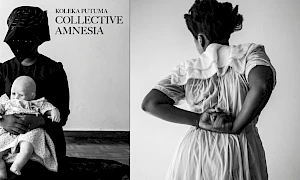

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

S come Silenzio

Maddalena FragnitoEN itInternationalismsSituated Organizations -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Cinq pierres. Une suite de contes

Shayma Nader–EN nl frInternationalisms -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Speaking in Times of Genocide: Censorship, ‘social cohesion’ and the case of Khaled Sabsabi

Alissar SeylaInternationalisms -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Today, again, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalisms -

Isabella Hammad’ın icatları

Hazal ÖzvarışEN trInternationalisms -

To imagine a century on from the Nakba

Behçet ÇelikEN trInternationalisms -

Internationalisms: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardInternationalisms -

Dispatch: Institutional Critique in the Blurst of Times – On Refusal, Aesthetic Flattening, and the Politics of Looking Away

İrem GünaydınInternationalisms -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand