Cultivating Abundance

Combining text, moving image and archival reproductions, ‘Cultivating Abundance’ traces the history of monocultural farming techniques, and their representation, in Sweden through the long-term research project of artist Åsa Sonjasdotter. Outlining the dangers of monocultural techniques, both ecologically and culturally, the project uncovers the vital work being done by counter-movements to the monopoly of large-scale agribusiness.

This is a story that begins from soil that accumulated comparably recently, geologically speaking. It is generated from clay that gathered by the fringes of the vast ice cap that covered the northern hemisphere until some 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. The retraction of the ice left behind vast plains of mineral-rich earth. Over the years it bore ground to oak and elm forests, where it became soil that would prove to be very generous for farming.

I would learn to know this soil intimately. I grew up in its habitats and by its waters, and I was fed from its yields, harvested in my family’s back garden. The scattered houses of the settlement where we lived were squeezed between vast farm fields where we kids laboured, weeding sugar beets in the summer. We should not drink the water from the wells, we were told, as toxic stuff used in the fields leaked into it.

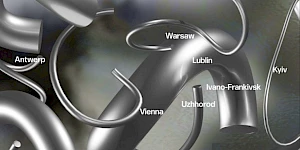

Extract from a map of southern Scandinavia, the region from which this research departs

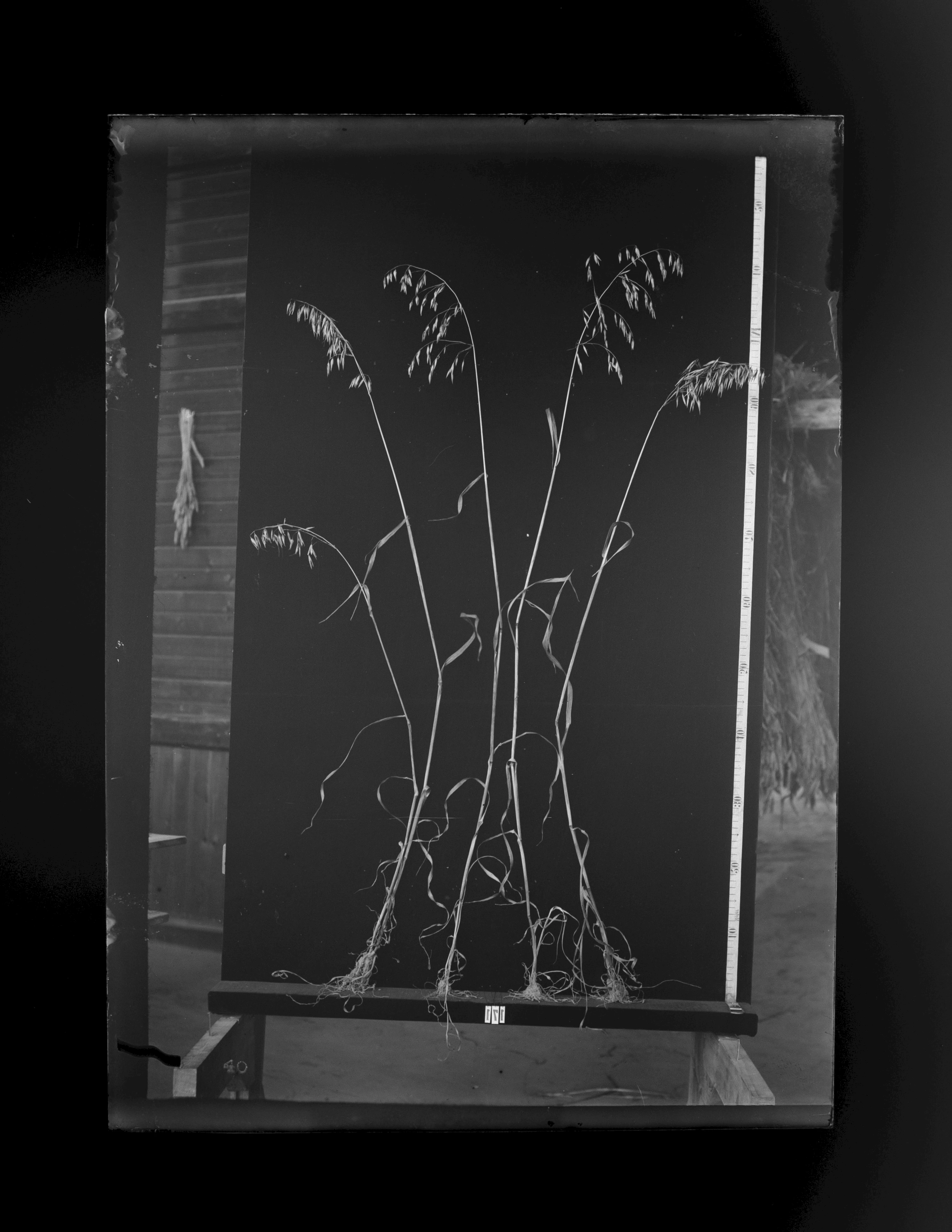

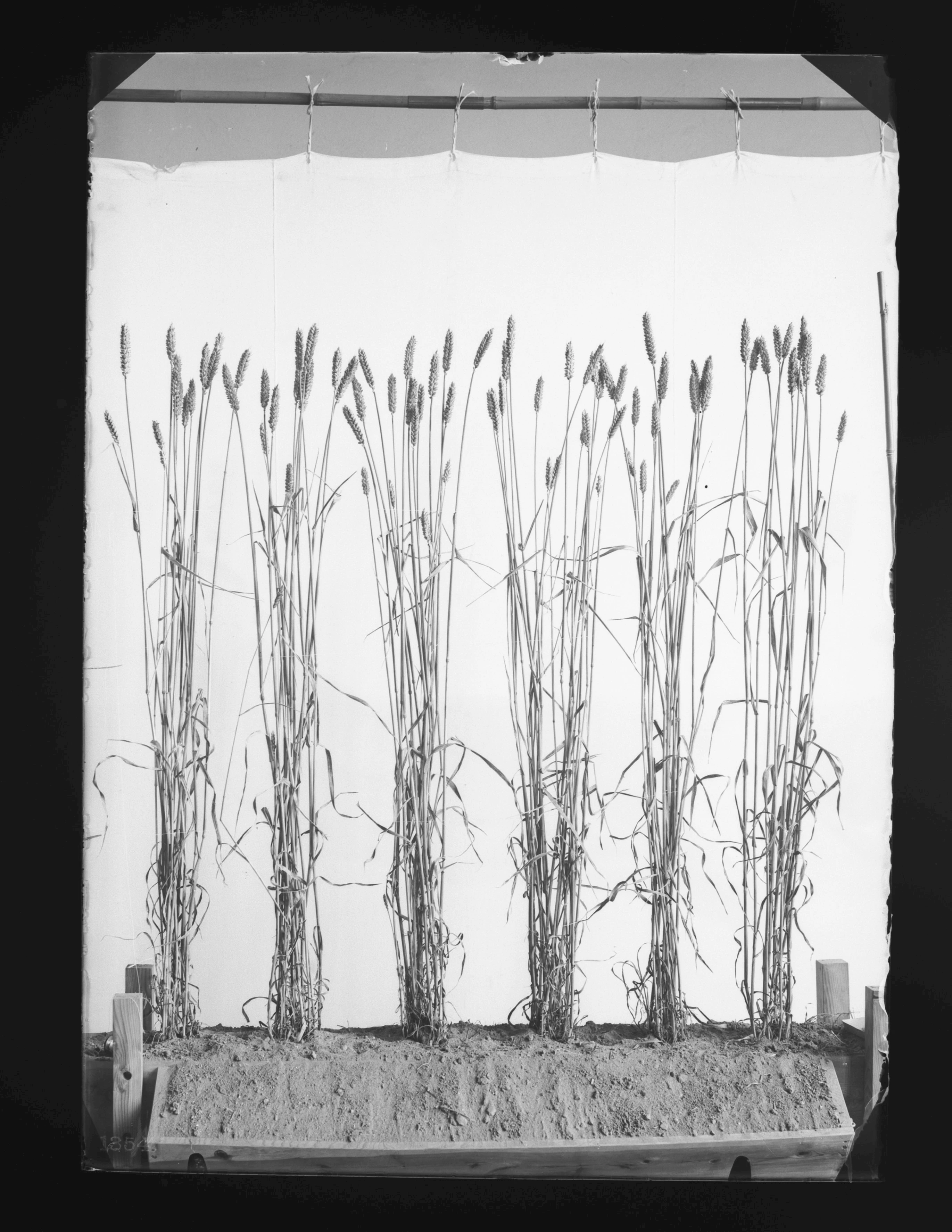

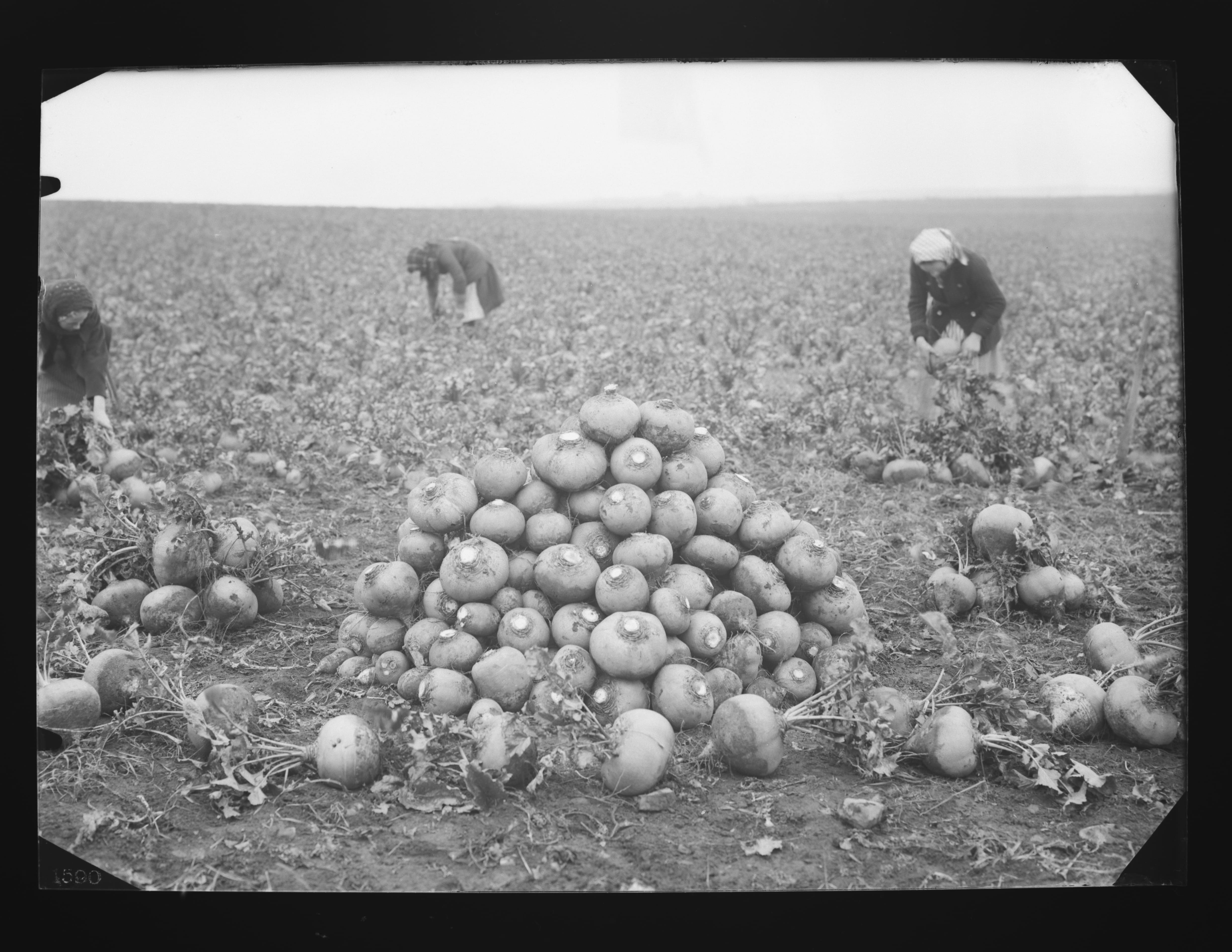

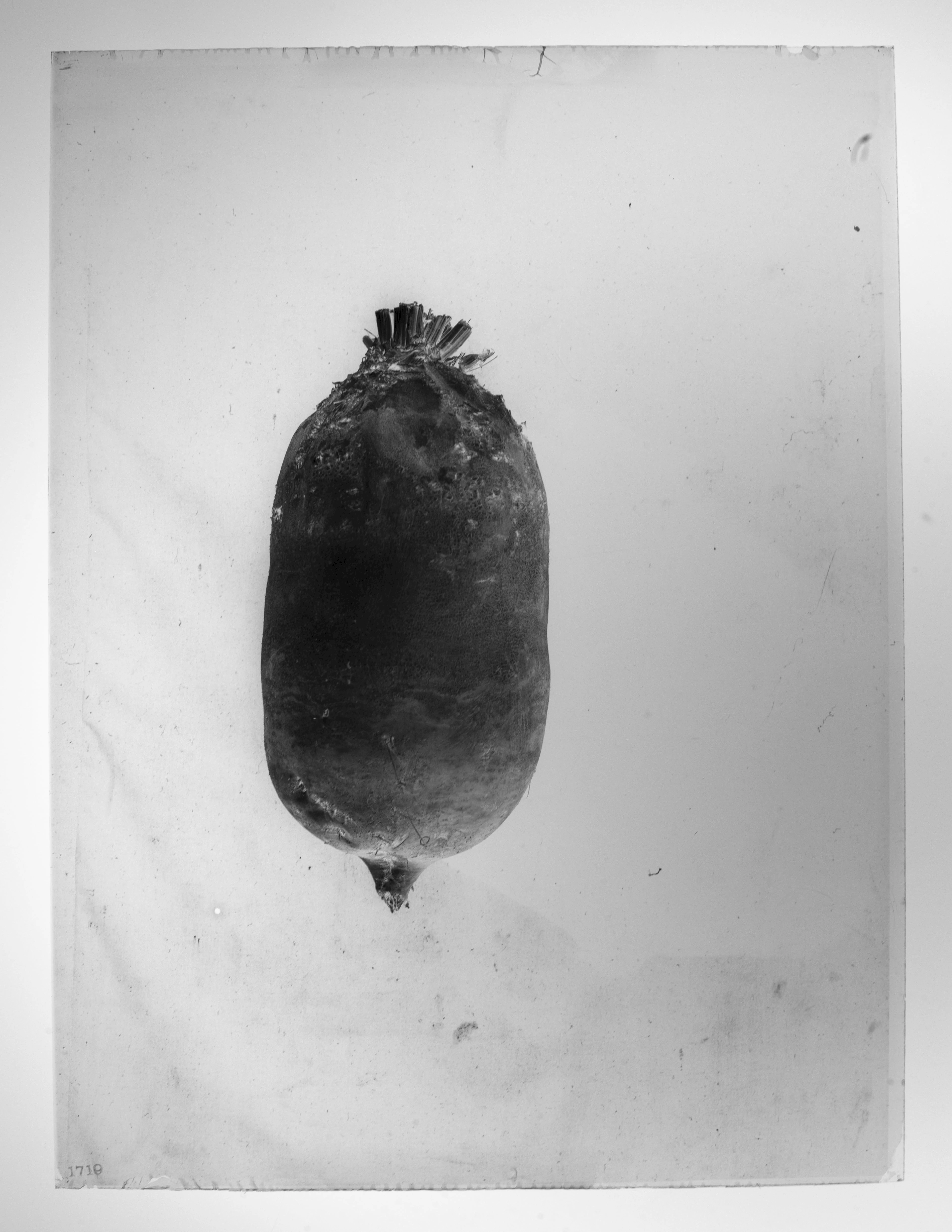

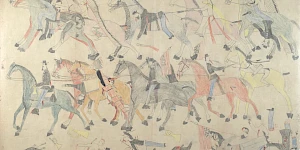

Fields of the Sveriges utsädesförening (Swedish Seed Association). Photography courtesy of Lantmännen, ca. 1907

Having grown up near these fields, yet with an unsettled feeling towards them, some twenty years ago I began looking more closely into their stories. One of the sites I visited for research was a local centre for plant breeding. When the janitor learned that I was a visual artist, she asked if she could take me to the attic; there were a few things she wanted to show me. Pointing at long rows of what I would come to learn were photographic silver-gelatine glass plates, stacked side by side across the floor, she asked, could you make use of any of these? The plates were covered in dust and pigeon droppings. The moments captured on these plates, I would later learn, documented the very first steps towards monoculture plant breeding as it is practised today by the global seed industry.

I continued researching this history as well as its counter-movements. The outcome of this research has been processed in various formats, among them the 2022 film Cultivating Abundance, made in dialogue with local seed association Allkorn (Common Grains) and plant breeder Hans Larsson. The film revisits the photographs and moving images recorded and then archived at this plant-breeding centre, which was later called the Swedish Seed Association. Further, it follows Larsson’s and Allkorn’s work to restore and regenerate still-extant peasant-bred grains that have survived the monocultural takeover.1

Tracing these events with respect to the soil, there was a decisive moment that brought about a shift in relation to the land – a shift that, in many ways, enabled monoculture farming to become a thinkable and even credible concept. Between 1749 and 1827, a few generations before the formation of the Swedish Seed Association, the Swedish state imposed land reforms in this region.2 For about a thousand years before the reforms, the land had been in the custody of peasant communities – even when it was owned by the church, by the crown or by lords. In this older system, each farming village formed a legally responsible entity. Thus, all of the village’s inhabitants were collectively responsible, for example, for tax payments. The land reforms compartmentalized the land and allocated each farmhouse of the village to one land unit. One member of each farming household became the private, legal owner of both the farmhouse and the land. The remaining people in the household had legal rights only through this person. In a patriarchal hereditary system such as this, this person was most often a man. The initiative to found the plant-breeding centre, which opened in 1886, came from farmers and landowners that had gained wealth through these reforms.

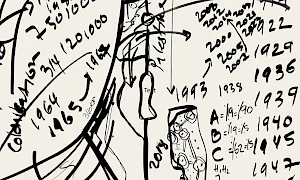

Excerpt from the film Cultivating Abundance by Åsa Sonjasdotter, made in dialogue with the plant breeder Hans Larsson and the Allkorn association, 2022

The voice-over of the film Cultivating Abundance (2022) introduces the purpose of the silver-gelatine photographs at the Svalöv Institute:

These glass plates document the very first years of the Swedish Seed Association in Svalöv. It was here that crop breeding for uniform crops was systemized, becoming the approach practised today by the global seed industry.

The breeders knew it was possible to grow uniform crops: Nearby, Copenhagen’s Carlsberg breweries had demonstrated this. Since the end of the 1880s, Carlsberg had cultivated a ‘pure’ yeast culture from a single strain of fungus. This enabled them to predict the outcome of the brewing process, making large-scale production much more efficient. So, the breeders in Svalöv applied the same method to plants.

This method was, in the words of the plant breeders themselves, a ‘total reversal of the old understanding’.3 Instead of saving selected seeds, which since ancient times had been understood as a regenerative, ongoing process of crop adaptation, breeders worked towards ‘recognizing and controlling the uniformity’ of ‘already existing’ properties in the seeds.4 The traditional understanding, that living matter is in constant flux was abandoned as a result of this shift. Instead, ideals were formed in resonance with theories of immutable laws of hereditary, such as those proposed by German friar Gregor Mendel in the 1880s.5

To put these theories into practice, selected plants were inbred over several generations until so-called ‘pure lines’ emerged from which genetic ‘contaminants’ had been removed.6 Crops showing traits of interest to breeders were taken from the fields to the clinical environment of the laboratory, where they first underwent the process of inbreeding. Once a varietal ‘pure line’ had been realized, it was then crossbred with a ‘pure line’ of a different variety of the same crop. The aim was to obtain a new, so-called ‘elite variety’ that would combine desirable features of both ‘pure’ strains in one and the same plant.7 This crossbred ‘elite variety’ would then be propagated in large quantities, to be sold and distributed over long distances for large-scale cultivation. The plant-breeding institute in Svalöv became internationally renowned, receiving prestigious study visits from scientists based at leading research institutes abroad.

The Sveriges utsädesförening (Swedish Seed Association). Photography courtesy of Lantmännen, ca. 1907

The technique of monoculture plant breeding was developed in conjunction with experimentation in the visual representation of uniform and standardized crops, using the recently invented technique of photography. The light-sensitive medium generated black-and-white images, emphasizing contrasts in volume and line while omitting colour. Early photographs show how photographers embedded at the institute developed a method of visually imposing ‘originality’ and patterned uniformity on the plants. Root crops were sorted and arranged into rows and grids in the field after harvest, or else attached to metal poles on wooden structures that lifted them into the air.8 A sheet was then placed behind each structure, whitening or blackening the surrounding environment. Indoors, a studio setting was created. Here, grains and root crops were placed in wooden boxes filled with soil to suggest a farm field, again with white or black sheets suspended behind them.

The production of such images ran parallel to the breeding of crops towards uniformity. However, as this breeding technique required up to ten growing seasons to achieve results, in the early years of the institute’s operation, it was the soon-to-be-obliterated peasant-bred crops that were used as props to visualize ‘originality’ and uniformity in the institute’s studio settings.9

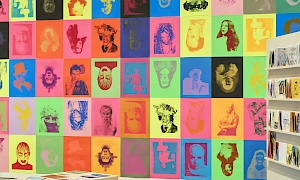

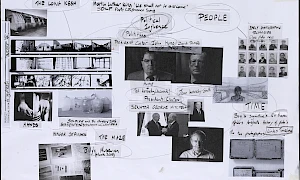

Parts of the photographic installation The visual process towards the image of uniform and original crops, presented at the Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6 October to 3 December 2023, and currently at Lunds konsthall, Sweden, 31 May – 26 August 2024

Disseminated through advertisements and thematic journals, these photographic representations of monoculture cultivation became vehicles for conveying a visual impression of what the agricultural landscape could become. Drivers towards the realization of an ‘original’ and ‘purified’ landscape, such images furthermore came to amplify what I call the eugenic imagination: voices from the eugenics movement would argue for the possibility – ultimately, the ‘duty’ – of ‘purifying’ and homogenizing life forms without restriction. The establishment of the State Institute for Racial Biology in Uppsala in 1922, an institution that politicians from all parties agreed would serve the common good, was directly fuelled by the results of the Swedish Seed Association’s activities.10

In 1936, together with geneticist Fritz Lenz, Erwin Baur and Eugen Fischer published their research in Human Heredity Theory and Racial Hygiene, a book that was to provide scientific justification for the biopolitical ideology of National Socialism.11 Baur and Fischer were, respectively, the directors of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Züchtungsforschung (Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Plant Breeding Research), founded in Müncheberg, Germany in 1928, and the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Institut für Anthropologie, menschliche Erblehre und Eugenik (Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics), founded in Berlin in 1927 – both directly modelled on Swedish equivalents.12

During and following World War II, food shortages incentivized increased state control of agricultural production for the Axis and Allied powers, a centralization of structures and standards that would benefit both totalitarian interests and commercial food industries.13 State-level approval of uniform plant varieties incentivized industrial seed producers to claim that they had the right to collect royalties on their ‘new’ and ‘original’ varieties, regardless of the fact that they had been engineered by the mining of peasant-bred seeds’ genetic code. Some of these producers would grow into multinational enterprises after the war. Based in Europe, they joined forces for the instigation of the globally purposed International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV). Its declared aim was to ‘protect’ the commercial seed companies by stipulating ‘universal criteria’ for defining ‘original’ varieties as such that were copied from standards developed under the Nazi-controlled agricultural sector in Germany and France during the war: distinctiveness, uniformity and stability (DUS).14 In 1961, UPOV passed a convention defining how the so-called DUS criteria are to be applied, and not only in relation to breeding.15 It further stipulates that only crops meeting the DUS criteria are permitted to be grown for the market by professional farmers. This obliges farmers to pay royalties to the breeders of these varieties, including when they save the seeds from their own crops for the next season. Today, the UPOV convention is fully ratified by seventy-seven countries, including those belonging to the EU. Currently, while other large agricultural countries such as Argentina, Brazil and India are in the process of ratifying the agreement, peasant movements and civil-rights organizations in West and Central African countries where UPOV is currently mobilizing to gain access are pushing back against its implementation.16 The fact that the UPOV convention is packaged into free-trade agreements (FTAs) and further bilateral and global trade agreements such as TRIPS (on intellectual property) and TPPI (on trans-pacific trade) makes the negotiation of their every detail more complicated.

Excerpt from the film Cultivating Abundance by Åsa Sonjasdotter, made in dialogue with the plant breeder Hans Larsson and the Allkorn association, 2022

Returning to Cultivating Abundance, another trajectory exemplifying the peasant counter-movement to the impositions of agrobusiness follows the work of plant breeder Hans Larsson. In the early 1990s, Larsson initiated a research project on ecological farm systems at the Agricultural University in Alnarp, South Sweden. As part of the research, extant local peasant varieties of rye, wheat, oats and barley that had been stored in the Nordic Gene Bank’s deep freezers, located on the university’s grounds, were test-cultivated on campus.17 In collaboration with the farmers who would later form the seed association Allkorn, the project was extended to test-cultivate the grains on farms in various other climate zones. With this step, Larsson and the Allkorn members began very slowly – so slowly that it went unnoticed as an act of dissidence – to move these peasant grains away from the system controlled by the monoculture industry and into the hands and soils of farmers.

One vital stage in this process was that of attuning the crops to the current climate and soil conditions, altered since the grains were frozen. Larsson describes how he undertook this procedure by building upon the concept of ‘evolutionary plant-breeding’, which has become the established scientific term for breeding using traditional techniques and varieties. Central to this technique is that it involves a diverse range of varieties; that it is based on selection instead of imposed crossbreeding, and that it takes place with and within the surrounding habitat:

In order to breed plants, you need to find locations that emphasize the climate and the environment. Everything about the surroundings is important: the trees, the water sources, and the wild plants as well. You are, in fact, co-creating an environmental space. This is a place that has become a breeding ground. Where the land itself and the trees play a part.

Excerpt from the film Cultivating Abundance by Åsa Sonjasdotter, made in dialogue with the plant breeder Hans Larsson and the Allkorn association, 2022

By the time the plants are in blossom, the film team revisits the breeding ground. Larsson continues sharing the process:

The breeding of evolutionary material is a fairly recent approach. A variety has to be stable and uniform in order for it to be registered. And this is the total opposite. They’re not uniform, they’re not stable. Quite the contrary, these have evolutionary capacity in them. They’re a blend of many different varieties. And that mixture means that they have lots of resistance genes as well. So, these crops are healthy. And in truth, this is the only route that will lead to disease-resistance in the future.

Excerpt from the film Cultivating Abundance by Åsa Sonjasdotter, made in dialogue with the plant breeder Hans Larsson and the Allkorn association, 2022

Moving to the breeding ground’s collection of wheat varieties, Larsson continues:

The heirloom material is often more diverse with regard to colour. We don’t know why they come in different colours, but it appears to be tied to the plant’s antioxidant content. I’ve used it as a criterion for selection; I like to use the colourful varieties. I see it as a form of communication between the plants and the breeder. And that the plants are signalling something. I’ve often noticed that this colourful material develops nicely. It’s an indication that something is happening at a deeper level as well. And if there is a change at the genetic level, the colours shift as well.

Since a few years ago, Allkorn has been running a self-organized seed bank for storing and redistributing the grains regenerated and rebred by Larsson. This enables the association to operate autonomously, away from seed monopolies. However, according to the ruling seed laws, the members of Allkorn are not permitted to exchange their grains beyond the association. The law recognizes the association and its members as one and the same juridical body – not unlike the legal status of villagers prior to the land reforms. Within this legal body, exchange is allowed. But since the association is growing rapidly – at the time of writing it has come to include more than 450 members – Allkorn is forming a critical mass, moving away from dependence on the state-authorized agribusiness monopoly.

Allkorn is one example of the many powerful initiatives that the global peasant movement is mobilizing against the enforcement of industrial monoculture farming and its resulting erosion of ecosystems, social structures and local economies. With La Via Campesina as one of the main coordinators, represented in Sweden by the association NOrdBruk, this movement is also mobilizing several unilateral legal complexes against the seed industries’ claims. Central to these is Article 19 of the ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas 2’ (UNDROP). The declaration was adopted in 2018 by the member states of the United Nations and marks a considerable shift in discourse. This statement defines and recognizes peasants, for whom traditional seed relations are central, as fundamental for food and agricultural production throughout the world. Further documents protecting traditional seeds are Articles 5, 6 and 9.3 of the ‘International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture’ (ITPGRFA), negotiated by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) for open access to seeds stored in public seed banks, as well as Article 31 of the ‘United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’.18 Ending seed monopolies is an important step towards opening up non-authoritarian and non-totalitarian agricultural relations with – and taken from and by – the soil.

Endnote: Abundance away from the scarcity/growth paradigm

The International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty (IPC), an autonomous and self-organized global platform that works at regional as well as global levels towards advancing food sovereignty systems, includes not only peasants, but also other practitioners excluded from and resisting the legislative dictations of agrobusiness, including women and youth: small-scale food producers and growers landless rural and agricultural workers, fishers and fish workers, hunters and gatherers, pastoralists and herders, Indigenous peoples, and food consumers. The platform has mobilized a set of terms that are used by the IPC and its member organizations, in their political negotiations with regional, national and international bodies such as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), to define peasants’ and Indigenous peoples’ practical, philosophical, social, and political conceptions. With regard to the term ‘traditional knowledge’, for example, the ‘International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture’ (ITPGRFA),19 which came about thanks to the negotiations of the IPC and other organizations, states the following:

Peasant and Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge encompasses all knowledge, innovations and practices that peasant communities and Indigenous Peoples have developed over time, and continue to develop in the present and future, in order to preserve and develop biodiversity and to use it sustainably. Traditional knowledge has the following key characteristics:

It is based on oral transmission;

It encompasses dynamic knowledge that is constantly enriched by peasant and indigenous innovations;

It is essentially collective knowledge that is embedded in a social system of communities.

All measures to protect traditional knowledge need to take into account these criteria.20

The IPC’s policy documents, which serve as tools for political negotiation, are developed within and between its member organizations. In this way, together with those of other organizations, the IPC’s millions of members constitute a ‘social system of communities’ that collectively collate, describe and redefine the ‘worlds’ and conditions of their practices and knowledge systems, as a means to halt and resist their violation by state-authorized global agro-industry.

The shift towards monoculture plant cultivation made cultivars a matter of conservation and of scarcity. Of the many thousands of grain varieties that grew in farmers’ fields in southern Scandinavia before monoculture breeding was invented and implemented, only around one hundred were still alive to be stored in the Nordic Gene Bank when it was finally established in the 1970s. Today, the remnants of their genetic data are monitored and controlled by large administrative institutions such as the EU Database of Registered Plant Varieties or the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. These costly apparatuses make peasants’ seeds dangerously scarce, a reminder that scarcity is always relational. In Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference (1996), geographer David Harvey elaborates scarcity’s political and ecological dimensions:

To say that scarcity resides in nature and that natural limits exist is to ignore how scarcity is socially produced and how ‘limits’ are a social relation within nature (including human society) rather than some externally imposed necessity.21

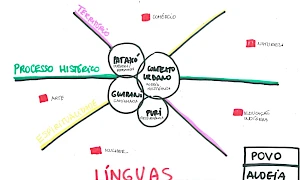

The process of slowly and repeatedly thawing frozen grains from the Nordic Gene Bank and reintroducing them into cultivation carried out by plant breeder Hans Larsson together with the Allkorn farmers, as described in Cultivated Abundance, is an insurgent act of rescue. In view of their initiative, the question arises as to why the seed industry was not convinced that monoculture varietals would come to reign without heavy legal protection. In the article ‘“The Goal of the Revolution Is the Elimination of Anxiety”: On the Right to Abundance in a Time of Artificial Scarcity’ (2016), the poet and scholar David Lloyd offers a response:

Perhaps, then, we need to recognize that precisely what neoliberal capital fears is abundance and what it implies. Abundance is the end of capital: it is at once what it must aim to produce in order to dominate and control the commodity market and what designates the limits that it produces out of its own process. Where abundance does not culminate in a crisis of overproduction, it raises the specter that we might demand a redistribution of resources in the place of enclosure and accumulation by dispossession. The alibi of capital is scarcity; its myth is that of a primordial scarcity overcome only by labor regulated and disciplined by the private ownership of the means of production.22

Considering Lloyd’s argument, how does abundance emerge, especially when starting from a place that for centuries has been marked by the paradigm of scarcity and growth? In Cultivating Abundance, Larsson describes how the process of traditional breeding, which generates an abundance in plant variation, cannot take place in an isolated laboratory. It needs to evolve in the living habitat, where ‘everything about the surroundings is important’. The breeders’ task here is that of ‘co-creating an environmental space’ in which the plants, according to Larsson, can thrive and open up for pollination. In line with Larsson’s description, the IPC’s policy documents emphasize the importance of the fact that peasant and Indigenous peoples’ traditional knowledge of plants emerges relationally, and which, as such, cannot be restricted to genetic information about a particular crop, variety, or plant characteristic. On the contrary:

[It] encompasses knowledge on how these plants relate with their environment and all other organisms or living beings that constitute the local ecosystem and, based on this, the ways in which they interact with other plants, animals and microorganisms, whether cultivated or wild, and the care to be taken in the event of problems related to the plants’ health, their nutritional and cultural use by human communities, etc. Furthermore, it is crucial to understand that such knowledge is embedded in a social system, meaning that it has been built in a community, and that it is continuously shared and enriched within this community.23

It is thus through the mobilization of peasant relationalities of cultivation, ‘through interaction with other plants, animals and microorganisms, whether cultivated or wild’, combined with continuous sharing, that communities in places marked by the paradigm of scarcity and growth (such as the agricultural landscape of southern Scandinavia, where this enquiry began) can contribute to the recovery of sensory relations and social responsibilities towards collectively generating abundance.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–tranzit.ro

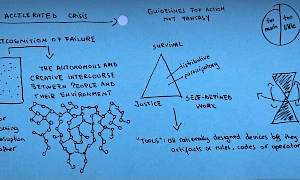

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–

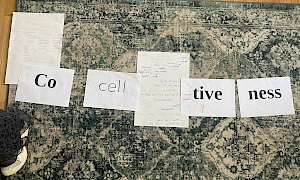

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

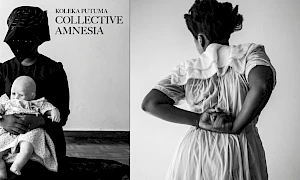

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

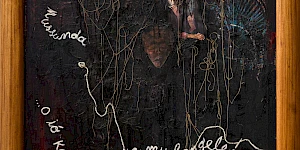

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Some Things We Learnt: Working with Indigenous culture from within non-Indigenous institutions

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations