Forget ‘never again’, it’s always already war

Cultural studies scholar Martin Pogačar reflects on never again from the context of the ongoing genocide in Gaza, and the multiple genocides that followed the proclamation of the phrase in the wake of World War II and the Holocaust. Pogačar traces never again, its different uses, temporal registers and grotesque imbalances of application. Exposing its performative emptiness, he details how a new ‘space has opened for the ruthless continuation and acceleration of necropolitical and colonial practices’. Countering this, Pogačar makes a plea for a politics of gentleness and for peaceful coexistence as a collective political project.

For a child growing up in mid-1980s Yugoslavia, the future was no elusive dream.1 Poised against the lingering traces of World War II and the looming threat of nuclear destruction, the idea of the future, paradoxically, entailed a peaceful and just world for all, based on the legacies and ongoing struggles of liberation and anti-colonial movements.

When I imagined the world in 2000, I also saw space travel and flying cars, clichés of tech-progressive imagery (at least, as I recall). Conversely, I never tired of listening to what it had been like in the old times: how it had felt seeing an orange for the first time and biting into it unpeeled, waving to a passing train, or seeing the static flicker of the black-and-white TV…

Most gripping of all were the wartime stories. My grandfather survived Gonars, one of the many (forgotten) fascist concentration camps, and my grandmother was denied her Slavic name in the fascist-occupied Primorska region along the present-day western border with Italy. My other grandmother lost her father in Ravensbrück … I listened with trepidation to stories about smuggling secret messages through fascist checkpoints, and was saddened by the fact that my other grandfather buried his violin in a forest when he joined the partisans, never to find it again.

These memories from ‘the war’, re-presencing fear, violence, and imminent death, were invariably interwoven with values of solidarity, respect for human and other life, and the acknowledgement that violence and war are not at all conducive to peaceful conflict resolution.

At the same time, resistance was always seen as the only right thing to do in the face of occupation and destruction. What is more, this attitude was imbued with ethics that transcended ‘mere’ liberation from the occupation, also entailing a socialist forging of a new and better world.

Looking back, Yugoslav socialism at least tried to conceptualize its own existence, in thought and practice, in wider humanist terms; it emphasized peaceful coexistence, itself perhaps one of the most positive international cultural and political projects to date and a central element of the ‘biggest peace movements in history’, among those seeking ‘post-war alternatives to domination and oppression … inventing new political languages of liberation’.2

Never again

World War II ended when ‘peace broke out’.3 Peace, however, was not (then or ever) evenly distributed. New conflicts were brewing, old ones were being reignited. Some wars are made famous in popular culture, effectively obscuring atrocities deemed less politically relevant, and so afforded less public attention. Even historical cases of genocide, such as that carried out by the Belgians in the Congo, the Armenian genocide, the more recent and relatively visible Rwandan genocide, or the one in Srebrenica, the first to have been committed in Europe after World War II. The suffering of the Kurds, the Rohingya, the Uyghurs and, yet again, of the Armenians, has been only peripherally reported by news media. Currently, coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Israeli genocide in Gaza and now escalating attacks on Lebanon, also due to their highly volatile political and military-industrial stakes, greatly exceeds that of other ongoing atrocities.

After World War II, a vow was (re)made never again to allow such atrocities and insanity to happen: a promise to posterity to forever prevent destruction and mass murder, to counteract (in a timely manner) the othering and hatred that led to the killing of civilian Jews, Roma, Slavs, communists, homosexuals and others who perished in the Holocaust, the epitome of industrialized suffering and destruction. Never again, the strongest of imperatives to learn from and not to repeat history, also powered, and was powered by, the drive for the material and symbolic reconstruction of what the British historian Keith Lowe calls the ‘savage continent’ – that is, Europe.4

Nevertheless, never again has a longer history. As Omer Bartov notes, it was first used after the ‘war to end all wars’ (what nonsense) – that is, World War I, then in the sense of ‘we should do everything we can to prevent another war’,5 which went on to empower notions of pacifism and appeasement. At the same time in the German context, however, Bartov continues, never again was used with a different interpretative emphasis, wherein:

We did not really lose that war. We were stabbed in the back. We were betrayed, and therefore that war has to be fought again. And this time, it has to be won. In that sense, World War I is re-interpreted in Germany, which leads into a National Socialist discourse, into a war that was lost for the wrong reasons and a war that should be won.6

In the Jewish/Israeli context after World War II, never again did not mean ‘never again war’ per se, but rather,

‘Never Again the Holocaust’. It’s not even really ‘Never Again genocide or mass murder’, it’s ‘Never Again the Holocaust’… . [And if] that thing should never happen again, then we should do everything we can to prevent it. In fact, everything that we would do to prevent it is justified. This gives one sanction to do anything one can or wants to if one perceives a particular threat, an existential threat.7

Finally, Bartov identifies another never again–type enjoinment, albeit one that doesn’t use those words precisely:

the communist one comes under the slogan of anti-fascism, that is that such systems of Nazism and fascism must always be prevented and that everything that we do to prevent it is justified … It’s a kind of ‘Never Again’ that gives one license to do whatever is needed to prevent that from happening.8

Note that even while this latter seems the most inclusive and open, as opposed to the more exclusivist ethno-nationalist interpretations, like all of the never agains Bartov mentions it is characterized not only by the urge to prevent future wars and genocides, but also by the speculative justification of violence in the very name of violence- and genocide-prevention.

Never again?

Declaratively, never again is past-oriented: a vow to remember the victims and prevent the forgetting of what happened. Thus understood, as Stef Carps and Michael Rothberg note, it may be seen as an impetus to remember and frame ‘traumatic histories across communal boundaries’ – as a tool, even, for the ‘transmission across society of empathy for the historical experience of others’, with ‘the potential, at least, to help people understand past injustices, to generate social solidarity and to produce alliances between various marginal groups’.9 Indeed, while the discursive and moral singularity attributed to the Holocaust (as identified by Michael Rothberg in his discussion of the criticisms of Holocaust-focused narratives) can sometimes obscure other atrocities or downplay traumatic events that may seem less violent, destructive or otherwise ‘not traumatic enough’, the collective memory of the Holocaust does offer a template to talk about and research other acts of violence in human history.10

At the same time, the main claim of never again is future-facing: to help chart out a different world beyond conquest, subjugation, mass killings, destruction. As such, post–World War II, it symbolized the potential to integrate the historical trauma of a generation and, as an articulation of hope for a peaceful future, radically inflected post-war politics and (popular) culture. It also influenced the practices and ideologies of decolonial struggles and the forging of political alliances among colonized nations,11 for example at the 1955 Asian-African conference in Bandung, Indonesia, the birthplace of the idiom ‘Bandung Spirit’. Darwis Khudori recalls:

I personally found that ‘Bandung Spirit’ represents a common wish for: 1) a peaceful coexistence between nations; 2) the liberation of the world from the hegemony of any superpower, from colonialism, from imperialism and from any kind of domination of one country by another; 3) the equality of races and nations; 4) the solidarity with the poor, the colonised, the exploited, and the weak and those being weakened by the world order of the day; and 5) a people-centred development.12

Similarly, the Non-Aligned Movement, kick-started in Belgrade in 1961, incorporated the idea of peaceful coexistence as one of its central tenets, effectively extending, or aiming to extend, the spirit and appeal of never again across peoples, nations and continents beyond the West.

Where, today, is never again? And where, in a world steeped in killing, destruction, exploitation and extraction, has it been for the past eighty years? Where is it as many of those in power actively contribute to the dismantling of any functioning approximation, however flawed, of an international order – of humanitarian law and other global institutions that were created to prevent the (re)barbarization of the world?

As the last survivors, witnesses and perpetrators of World War II pass away, as states and ideologies collapse, new ones arise and, consequently, geopolitical relations shift, the values, dreams and expectations that were derived from the ruins have increasingly become the stuff of pro-forma political statements. Take, for example, this Holocaust Remembrance Day statement by the German Ambassador to Egypt, made roughly eight months before 7 October 2023:

It is our duty as a nation and as humans, to keep the memory alive and make sure that history does not repeat itself. Never forget, and never again. This became a supreme priority of our education, and of our Foreign Policy. Today this means fighting against any kind of discrimination, racism, antisemitism, anti-Islamism, and hate, which is again on the rise in our societies. This begins at the grass-root level of our societies, in education in schools, and in local and religious communities.13

To and for whom, then, does today’s never again apply? Why has it become a discursive trope applied only in hindsight, after atrocities have been committed? What conditions have brought about its near-demise or degradation, or rather exposed it as a façade?

Never again, for whom?

New instances of aggression and war can no longer be understood in the historical and mnemonic frame of the twentieth century. Nor, for better or worse, can past wars and destruction be understood in the frame of a market capitalism that, arising ‘victorious’ after the ‘defeat’ of socialism as an emancipatory project, has since evolved into a cynical legitimation of state-sponsored violence as a fight for ‘democracy’ and ‘freedom’. However noble these values may be, their application in contemporary conflicts is marred by ‘cancelling’, censorship, hypocrisy, ‘alternative truths’ and outright lies, among other misuses of language (or images, for that matter). As noted by Ursula K. Le Guin: ‘To misuse language is to use it the way politicians and advertisers do, for profit, without taking responsibility for what the words mean. Language used as a means to get power or to make money goes wrong: it lies.’14

Worse than anodyne, never again increasingly comes across as a grotesque political lie. Its performative emptiness, emancipatory devaluation and selective application typifies the for-profit use of high-flying terms such as ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’, or ‘human rights’, in ways that rest on binaries of absolute ‘good or evil’, ‘right or wrong’. Such terms, so used, only contribute to the bloody, exclusionary, arbitrary, selective, religio-mythical ‘realities’ that serve to reinforce or even constitute divisions between those lives that are worth living and the rest.

Such is the case in the ongoing genocide in Gaza perpetrated by the State of Israel,15 whose slaughter and racial optics demonstrate the selective and exclusionary character of the Israeli state’s never again, almost from its outset: Three years after the end of World War II, following the establishment of the State of Israel in 1947,16 the 1948 Nakba resulted in the destruction of Palestine and the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians. Per the UN’s webpage ‘About the Nakba’:

As early as December 1948, the UN General Assembly called for refugee return, property restitution and compensation (resolution 194 (II)). However, 75 years later, despite countless UN resolutions, the rights of the Palestinians continue to be denied. According to the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) more than 5 million Palestine refugees are scattered throughout the Middle East. Today, Palestinians continue to be dispossessed and displaced by Israeli settlements, evictions, land confiscation and home demolitions.17

Yet the Nakba continues to receive little recognition or notice in western media or official political discourse.18 As Michael Mann observes, one thing that ‘makes this situation unique’ is the fact of its ‘involving the imposition of a settler-colonial state upon indigenous people by another people, fleeing a genocide’. Mann goes on:

Liberal assumptions might suggest that the terrifying experience of the Shoah would make Israeli Jews more sensitive to others’ suffering. To the contrary, many seem to believe that to survive as a people, they must use to the full whatever coercive power they have. Since Israeli Jews have the military and political power to seize Arab lands, most believe they have the right to do so in the name of ethnic survival.19

For never again to work post–World War II, it was deemed critical to redefine the system of transnational relations, international laws, and treaties and, once redefined, to include the newly decolonized nations within them. The United Nations, as the only approximately capable entity, was tasked with providing forms of global governance. This task was, and is, difficult to uphold. As a manifestation of the prolonged legacy of western imperial subordination, international law was, and is, innately biased: it has no actual leverage to coerce signatory parties to comply, particularly when a decision or action might be in conflict with the interests of those with political and military power. Nevertheless, in a technologically, economically and politically connected world, planetary institutions seem crucial to facilitate trans- and international contracts, cooperation and solidarity across territories yet within legal boundaries. Here, an exchange of letters between Hannah Arendt and Karl Jaspers is worth revisiting.20 Referring to the trials against Nazi officials, Arendt wrote:

The Nazi crimes, it seems to me, explode the limits of the law; and that is precisely what constitutes their monstrousness. For these crimes, no punishment is severe enough. It may well be essential to hang Göring, but it is totally inadequate. That is, the guilt, in contrast to criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems … . And just as inhuman as their guilt is the innocence of the victims. Human beings simply can’t be as innocent as they all were in the face of the gas chambers (the most repulsive usurer was as innocent as the newborn child because no crime deserves such a punishment). We are simply not equipped to deal, on a human, political level, with a guilt that is beyond crime and an innocence that is beyond goodness or virtue. This is the abyss that opened up before us as early as 1933 (much earlier, actually, with the onset of imperialistic politics) and into which we have finally stumbled.21

The arbitrary attribution of e.g. political, racialized, gendered otherness as a discursive (becoming, all too often, a biophysical) precursor of genocide is a mechanism of dehumanization to structure the ground for actions that, post-festum, are often called ‘evil’. More specifically, Arendt used the term ‘radical evil’ for that which:

has to do with the following phenomenon: making human beings as human beings superfluous (not using them as means to an end, which leaves their essence as humans untouched and impinges only on their human dignity; rather, making them superfluous as human beings). This happens as soon as all unpredictability – which, in human beings, is the equivalent of spontaneity – is eliminated.22

Such framing amplifies the other’s status as an enemy, readily transformable into a screen onto which fear and hatred are projected; this drives the formation of a mass psychosis in which things get physical. Punitive action, removal of degenerates, remigration (recently popularized by the extreme right) as ‘deratization’ – pest control, literally, getting rid of (human) rats – become acceptable methods of protection and security.

In his reply to Arendt regarding the question of guilt, Jaspers noted:

I’m not altogether comfortable with your view, because a guilt that goes beyond all criminal guilt inevitably takes on a streak of ‘greatness’—of satanic greatness—which is, for me, as inappropriate for the Nazis as all the talk about the ‘demonic’ element in Hitler and so forth. It seems to me that we have to see these things in their total banality, in their prosaic triviality, because that’s what truly characterizes them.23

And since ‘we’ are ill-equipped to deal with actions that are ‘beyond crime and innocence’, ‘beyond goodness or virtue’ – actions that undermine lawfulness as a basis for preventing or sanctioning crimes against humanity – it should be clear to us all that it is necessary not only to devise a planetary system to deal, however precariously, with such acts of ‘radical evil’, but also to identify and prevent the escalation of conflict before it oversteps the boundaries of humanity and legality.

In the wider contemporary framing, as per Arendt, the othering logic of good vs. evil – whereby ‘their’ absolute guilt (vs. ‘our’ absolute goodness) is what drives ‘us’ to strive for ‘our’ ultimate victory and ‘their’ defeat – also helps to understand how and by whom the international system is presently being dismantled. Actions in breach of international treaties and organizations are often legitimated by a neo-nationalist, my-country-first affective logic, subject only to the power-based and otherwise arbitrary non/enforcement of ‘the law’. And it is from this, too, that the persistence and impunity of certain actors derives. For example, the US’s construction of a floating pier on the Gaza shore, now abandoned, effectively bypassed international humanitarian institutions whilst also assisting Israel in indefinitely preventing the arrival into Gaza of aid by land. Such unilateral actions, conducted via semi-transparent processes outside the scope of international institutions, undermine international efforts at conflict resolution, as well as the institutions themselves. They also routinely legitimize and normalize extraction and privatization in zones of conflict, securing terrain for (nationally favoured) corporations to operate with little social or political accountability.

In such circumstances, never again is not just an opportune political lie, a pervasive form or feature of political performativity, it is a failed ideal. Promoted as an all-human value despite its implicitly partial or exclusionary nature, it alludes to a better future even while it systematically fails to account for the mechanisms that drive atrocities, such as the techniques of detention and killing that culminated in, but did not end with, the Holocaust.

Now, in light of the ongoing genocide in Gaza, never again is also shown to be an utterly shattered promise of a better world.

Always already again

After the collapse of socialism, a ‘victorious’ liberal capitalism eradicated any politico-ideological alternatives, striving to deride into forgetfulness the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which, post-war, had presented a political and economic alternative to the bipolarity of the socialist-east and capitalist-west systems. As such, it also offered major contributions and support to decolonial and anti-imperial movements across the globe, in the name of autonomy and self-determination.24 As mentioned above, one of NAM’s central tenets was the idea of peaceful coexistence among its members, based on the awareness that, while a world without conflict is impossible, it is possible to use methods of conflict resolution other than violence and war. Yet, ‘after NAM’ and ‘after socialism’, the world has effectively shaken off both the shackles of lawful conduct and, with them, the futurophilic obligations of never again in full spectrum – that is, the undertaking to work towards a peaceful and just future for all. Instead, a space has opened for the ruthless continuation and acceleration of necropolitical and colonial practices, now evident, yet again, in the decimation of Palestinian lives, lands and lifeworlds – just where an opportunity to fully enact a (re)commitment to never again has, once again, been lost.

To grasp, instead, the full consequences of its liberal renunciation, it is necessary to consider the longer, reality-structuring sociopolitical, historical, technical and economic processes and phenomena that preceded it: On the one hand, the wider effects and affects of the processes of capitalism and industrialization that, for humans, recast the relationship between time and place, decoupling us from a nature relegated to the status of a set of extraction-ready resources; on the other, those of a liberalism that historically and consistently traded political for economic power, leaving the former to conservative, proto-fascist and fascist actors.25

These processes, integral to modernity’s scientific discoveries and technological advances, in particular the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century, were marked by what the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa calls ‘social acceleration’,26 leaving a significant imprint on the future development of science and technology, on material and symbolic landscapes, and on the way politics has been hollowed out. Thus, as Rosa states, social acceleration has deeply affected the conditions of modern industrial human relations with others and with the world:

The sociocultural formation of modernity thus turns out to be, in a way, doubly calibrated for the strategy of making the world controllable. We are structurally compelled (from without) and culturally driven (from within) to turn the world into a point of aggression. It appears to us as something to be known, exploited, attained, appropriated, mastered, and controlled. And often this is not just about bringing things—segments of world—within reach, but about making them faster, easier, cheaper, more efficient, less resistant, more reliably controllable.27

The obsessive quest to control the world has propelled modern industrial humans into an evermore aggressive relationship to nature, legitimizing and normalizing the desire for, and the operational mode of, conquest:

Everything that appears to us must be known, mastered, conquered, made useful. Expressed abstractly, this sounds banal at first—but it isn’t. Lurking behind this idea is a creeping reorganization of our relationship to the world that stretches far back historically, culturally, economically and institutionally but in the twenty-first century has become newly radicalized, not least as a result of the technological possibilities unleashed by digitalization and by the demands for optimization and growth produced by financial market capitalism and unbridled competition.28

Effectively, what this means, in the context of the neoliberal takeover of mind and body, land and time – or, that is, their recasting as resources, Heideggerian Bestand – is that everything and everyone becomes a ‘radical enemy’. Contra NAM, this ideological and material optics posits victory, domination (or financial gain, for that matter) and destruction as the highest goals or values – with application not only to treaties and laws, but also to ‘the environment’ (i.e., the planet, understood as a set of natural resources). Ultimately, all life, in its unpredictability and spontaneity, could be subject to elimination under this rule.

A world approached via the motto ‘move fast and break things’29 has no use for never again, nor for peaceful coexistence; no room for thought, no time to listen and hear and ponder; no need to reflect and debate, no use for empathy, solidarity or care. There is, however, plenty of room for war and destruction. War, according to Darko Suvin, ‘is more than a metaphor for bourgeois human relationships, it is their allegoric essence’;30 or, as noted by Jean Jurès: ‘le capitalisme porte la guerre comme la nuée porte l’orage’;31 or, as Rosa Luxemburg concluded: ‘force (Gewalt, violence) is the only solution for capital: accumulation of capital accepts violence as permanent weapon, not just at its beginning but also today’.32 ‘Continued warfare under capitalism never stopped’, Suvin adds, before exemplifying his insistence that any discussion of modern warfare be cast in class terms: ‘sabres, bullets, and bombardment was always the final answer of the upper class – first feudal landlords, then centralised state armies – to any bottom-up justice-seeking uprising’.33 It is of little consolation that, according to Isaac Asimov, ‘violence is the last refuge of the incompetent’.34

This dynamic inflects the present and future prospect of peaceful coexistence. It uncovers the conditions that drove the industrialization of killing and, just as importantly, alludes to the conditions of neoliberal totalitarianism. The latter – escalating a bellicose technopolitics that actively prevents and disempowers the peaceful resolution of disputes in favour of profitably arming one or more of the disputants – declaratively embraces never again at the same time as it cynically disempowers it by continually promoting (increasingly neo-nationalistic) violence and war as ‘humanitarian’ tools for conflict resolution, and discouraging or censoring critique.

If, however, one is to fight against the Denkverbot that seems to arise from this situation,35 against the cynical imposition and naturalization of radically exclusive and mythologized relations between good and evil, ‘us’ and ‘them’, against subjugation and destruction, against the legitimization of war as an acceptable solution, one is – that is, ‘we’ are – required to attempt a substantial conceptual as well as actual reconfiguration of ‘our’ conditions and modes of human, nonhuman and environmental relationality, ‘our’ catastrophic overvaluation of financial ‘sustainability’ or ‘gain’.

Today, any answer to the question of the future relevance of never again must avoid a binary ‘yes or no’, ‘us or them’, ‘victory or defeat’. Not simply because the mantra has, so far, exclusively applied to the west, but because the very conditions and prospects of life amid the post-Enlightenment–technofeudalist–neoliberal–extractivist entanglement are premised on aggression and violence. Aggression, following Rosa, can be understood as a structural, political, economic and affective mode of operation: to be rendered controllable, we are increasingly compartmentalized, polarized, disoriented, neurasthenic subjects, apparently continuing to lose political and cultural agency in the face of seemingly insurmountable eco-political crises. Yet, in fact, we should be seeking to form radically different structures and practise radically different politics of solidarity, equity, care, kindness and gentleness as a substrate for decisive socio-ecological action.

In this, attention should be paid to the power of gentleness, which, as Anne Dufourmantelle describes it, ‘is an active passivity that may become an extraordinary force of symbolic resistance and, as such, become central to both ethics and politics’.36 Today, however, ‘gentleness is troubling. We desire it, but it is inadmissible. When they are not despised, the gentle are persecuted or sanctified. We abandon them because gentleness as power shows us the reality of our own weakness.’37 The same could be said of those striving for peace who have consistently been cast as cowards and traitors.38

Finally, the question of whether the present extractivist neoliberal regime can accommodate any coherent, transformative and historically informed discussion of peaceful coexistence and never again reveals a twofold obstacle: First, that the apparent desire to understand the world as hostile (per Rosa, above) breeds generalized violence and aggression; and second, just as crucial, that as past traumas recede into the distance, future generations become immune to violent images and stories from the past.

For many people today, the never again war of nearly a century ago, its deportations, mass killings and destruction bear little emotional resonance. In the face of this, Darko Suvin asks: ‘How can we outline a new sensorium humanity needs for continued existence?’39 For, indeed – and despite the taint, in living memory, of the term and concept of revisionism by, for example, Holocaust denial40 – Hans Kellner insists:

It is the nature of an active historical culture to revise. Each new contribution to the discourse … must acquire its own identity by foregrounding those features which deform and challenge the sense of the material. … To be brought to life, or at least to the simulacrum of life that makes possible academic or even popular publication, the material will have to be reshaped, and this, in turn, means revision. The alternative is ritual, and even ritual is always open to the demands of the present.41

The ways in which historical knowledge is produced, reproduced, disseminated and popularized, not just through education but also in popular culture and media, must be continually reinvented, recalibrated and updated in such a manner that ‘the past’ can ‘speak anew’ to new generations. Like this, it might affect them – as in, move them and make them move – in novel ways,42 preventing mnemo-historical negationism and amnesia from feeding (off) political lies.43

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

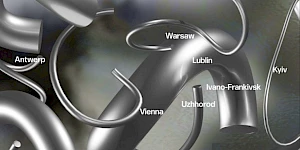

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–tranzit.ro

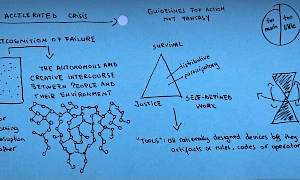

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

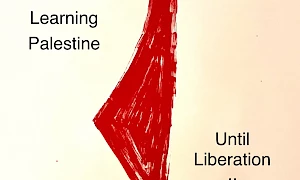

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

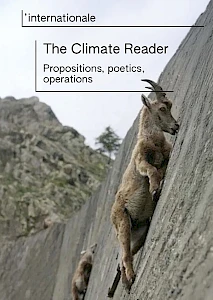

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations