…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

In his essay ‘And the earth along… Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world’, researcher Martin Pogačar (ZRC SAZU, Ljubljana) introduces the framework for the ambitious eponymous publishing project within the context of Museum of the Commons. The project aims to explore how humans and non-human ‘relate to their worlds’ through trans-disciplinary research and diverse forms. Entering through ‘fire, steel and particles’ the essay – and the project to follow – traverses histories and conceptualisations of natural phenomena, technology, industry and extraction, knowledge and the imagination, as well as the politics underpinning ‘cosmotechnics’, philosopher Yuk Hui’s term to describe the coming together of the cosmos and the moral.

This essay is also the occasion to launch an open call for contributions, which can be viewed here. The text is the first in a series dedicated to ‘And the earth along…’ and will be followed by the short story Indra’s Web by science fiction writer Vandana Singh.

The Earth undergoes frequent, continuous and radical changes, as does the rest of the universe. Over about four-and-a-half billion years, our home planet has seen the formation and transformation of continents; it has witnessed the emergence of life and six major extinction events, with the penultimate of these unfolding now.1 From the perspective of a human lifetime, such scales of time and physical change are hardly perceptible, barely conceivable. The dimensions of the expanding universe are difficult to fathom, and it is no easier to imagine the expanses of deep time; the ferociousness of such changes, unfolding incrementally over hundreds of thousands of years; or the abundance of natural and, more recently, human-made events that have contributed to the making, remaking and unmaking of the Earth into the planet that humans know today – or at least, think and hope they do.

Humans can (only) know the world inasmuch as it is revealed to them through observation and experiment: through probing and poking, tasting and smelling, thinking and contemplating. Along the way, they are continuously reinventing, and are reinvented by, their various tools and technologies: apparatuses and measures that work as exosomatic organs, mediating between the world (experience) and us (contemplation),2 enabling their creation and understanding, their thinking and doing, and among these are gauges with which humans sort, codify and categorise the world. How they are used is shaped by love–despair–memories–hopes–dreams–disappointments, as well as by material destruction–war–conquest–subordination, and by reconstruction–invention–creation. Yes, it is cyclical.

Increasingly, humans have come to be seen as a geological force in the Anthropocene and are now urged to recalibrate the stable-world perspective and think about the planet changing in front of our eyes. There is little time to act to mitigate the consequences of what philosopher Yuk Hui calls ‘blind modernisation’,3 driven by (western) science and technology and marked by exigencies of ‘progress’ and ‘development’, the conquest and subordination of ‘nature’, and the related extractivism and consumerism. This is what is driving the acceleration of cultural, environmental, social and political disruption and upheaval.4 Yet ‘progress’ and change, as well as development, acceleration and destruction, could not have happened were it not for a primordially thorough and radical entanglement of the human and the world through technology, which, in this context, is taken to refer to ‘the most basic level of things that are selected or made to fulfill a function to a user’.5 This primordial entanglement constitutes what Yuk Hui terms cosmotechnics: ‘the unification of the cosmos and the moral through technical activities, whether craft-making or art-making.’6

**

Let this introduction set the stage for reconsidering how humans relate to other humans and nonhuman beings, their worlds and the Earth, through elements and related phenomena. Of these, I propose to focus here on fire, steel and particles (while not excluding others such as water, clay, plastic, fabrics, wood) – a set that is, and has been, crucial to substantial changes in human and planetary histories, bridging chemistry, physics, biology, anthropology, history, the arts and the ‘humanities’. The mastery of fire meant the birth of technics; steel (its production and its use) is the epitome of industrialisation; and particles, the constituents of everything there is, bear the promise of endless energetic resources. However, inasmuch as these are, and have been, used to make the world, they are also inadvertently involved in the unmaking of the world, life, and even the planet.

This text, then, is a proposition to (re)think, (re)write and (re-)experiment with and about the theories and practices that (not only) fire, steel and particles, their histories and presents, afford; the agency they (de)limit; the world they (re)shape, and how; what they make visible and what they conceal or erase; what injustices they enhance, and what strategies of resistance they encourage.

**

Humans have been made so, in and through interaction, mutual influence and coevolution with the environment and (other) human and nonhuman beings, including with technology. The fact that humans are made in entanglement with technics, tools and apparatuses must not be understated7– nor should the fact that technology is, by definition, neither good, bad, nor neutral, per Melvin Kranzberg’s emphasis.8 In fact, technology is a pharmakon, as Bernard Stiegler states: a remedy and a poison, an enabler and a disabler.9 Any interaction with it is necessarily also pharmacological. Technology can be used to create and destroy, to develop and regress, to heal and to hurt – to make, remake and unmake.

This pharmacological entanglement, then, is the backbone of a book-in-the-making, at the interstices of scientific expertise and feats of imagination. Fire, steel and particles, having affected and shaped humans’ histories, carry historical, material and emotive resonance, helping us to unravel the social, cultural, political and technological conditions and effects of human interactions with others, and the environment. This perspective is necessary in any attempt to come to terms with the pharmacological condition in thinking about the past, present and future of humans, nonhuman beings and the planet.

**

Fire, Prometheus’s gift in the western tradition, is arguably the first technology humans have ‘conquered’ and ‘mastered’. According to Bernard Stiegler, it is the pharmakon par excellence: a civilising process, it is also a constant threat to civilisation – the risk of being on fire.10 Although few archaeological records are known to exist that reveal much detail about its early use, it has been humans’ adversary and companion for ages.11 Fire, naturally occurring in the wild due to strikes of lightning, may perhaps have taken care of the first roast and scared away that hungry bear. Still, at first it was in its essence an ephemeral and geographically limited phenomenon. It was more common in the steppes than in the jungle, for example, and once it died, there was no more.12 When humans domesticated fire, it was used for cooking and preserving food. It made food more tender and easily digestible (and so possible to ingest in larger quantities), freeing up chewing time and energy for other activities.13 What is more, this is believed to have resulted in an increase in human brain size (from 600 to 1300 cc) during the Pleistocene. And, as a larger brain is more energy-consuming, this, according to J.A.J. Gowlet, then resulted in ‘increases in group size and the pressure toward social cognition, which also constitutes a link with language origins.’14

Fire provided protection and warmth, and was later also used in making and forging of tools for creating fertile land and weapons for destroying enemy settlements. It was sanctified in religious practices. Later, with the Enlightenment and particularly during the Industrial Age that followed the emergence of cities and ensuing urbanisation, fire was ‘intellectually transmuted’: ‘devoluted from a universal cause to a chemical consequence, the mere motion of molecules, the quantum bonding of oxygen.’15 Uncontained, it came to be understood as ‘alien, a destroyer of cities, a savager of soil, a befowler of air, an emblem (in science and in agriculture) of the hopelessly primitive’.16 The historical transformation of fire was substantial:

Ancient fire practices had mimicked nature; now technology provided the model for how nature worked, or ought to work. Not flame but the heat engine was the exemplar for animal metabolism and the source of inspiration for how heat was created and transferred. Natural philosophy found conceptual surrogates for fire. Chemistry subordinated fire to the atomic bondings of oxygen. Thermodynamics segregated fire from motion and heat. Electromagnetic theory divorced it from light. The concept of energy replaced the universal suffusion of fire throughout nature.17

The once fleeting spark of fire could be harnessed in science and industrial technology to trigger reactions and create new materials, driving the heat engine and the Industrial Revolution. Fuelled by wood and fossil fuels, it burned in furnaces and in locomotives; it illuminated streets and, in early industrial plants, teased out from various materials and new compounds their hazardous and sometimes deadly fumes.18 Fire has ‘underpinned the development of all modern technologies – from ceramics, to metal working, to the nuclear industry.’19 Once contained, and once it can be kindled at will, fire can be used for a myriad of purposes. Properly fed, it reaches temperatures higher than those needed to cook food or heat up a house: it can melt quartz into glass and it can be used to melt and then to shape metals.

But fire – ‘the symbol of technical knowledge, the fabrication of arms … but also the fire of desire that takes care of its object’20 – also freed up time: it opened up space to ponder and think, to be bored and to dream. Having affected the brain by means of altering nutrition and exposing it to new chemicals (smoke, food), thus affecting the exosome,21 fire contributed to the rewiring of neurons that started ‘firing’ fiction, poetry, narratives, history; it illuminated cave walls that became the artist’s proto-canvas, while the hearth became the site of communal life and storytelling.

**

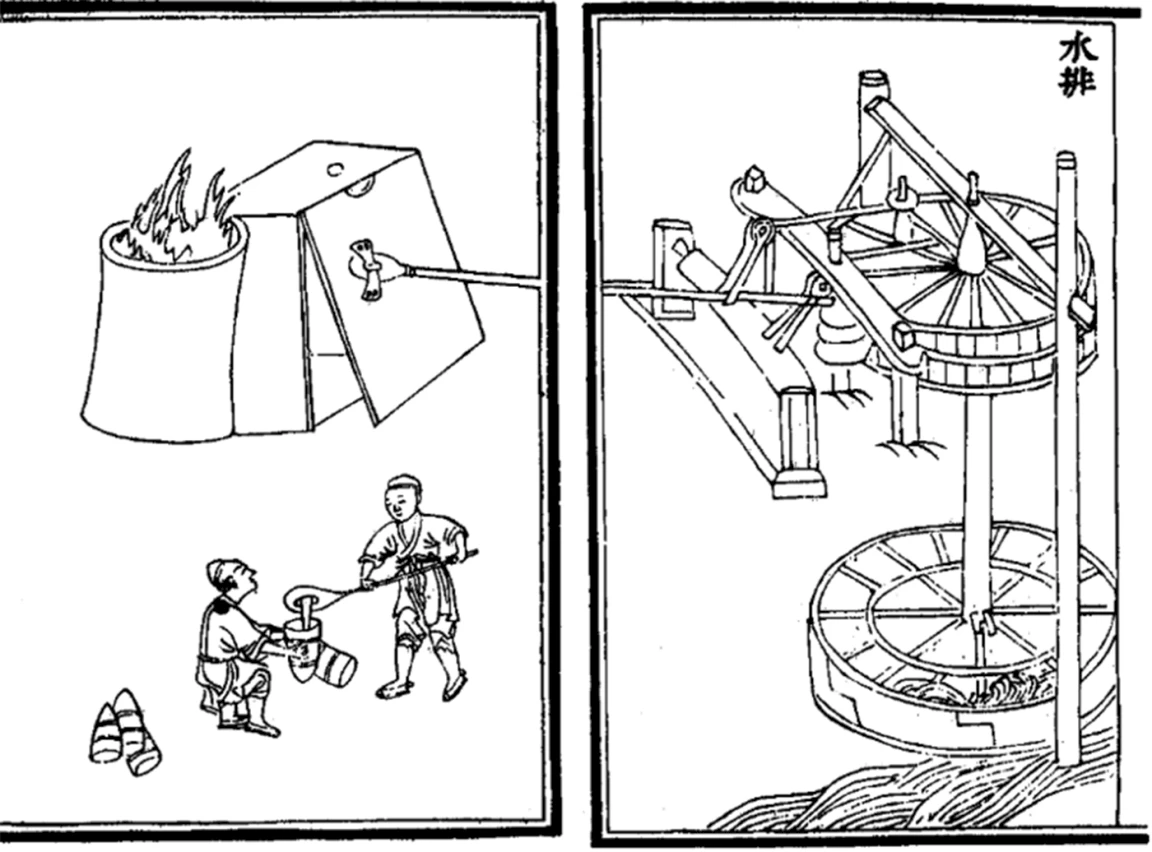

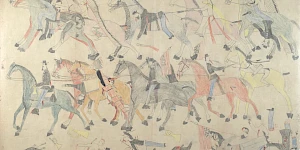

Medieval printed illustration depicts waterwheels powering the bellows of a blast furnace in creating cast iron. Illustration taken from the treatise Nong Shu, written by Wang Zhen (1313 AD) during the Chinese Yuan Dynasty. Date 1313 AD. Source: Wikipedia

Metals do not normally appear ‘out there’ in pure form, but have to be extracted, separated and purified. Still, the first metals to be used by humans, the archaeological record shows, fell from the sky. A meteorite apparently brought some iron to the Earth, where it was found and wrought to make King Tut’s dagger – one of the first such finds.22 Only later was it discovered, in the Near East about 2500 BCE, that metals were also hidden in Earth’s underworld, mixed with other elements. To obtain them in their pure form required practice and knowledge of how to apply heat to purify the ore. This necessitated the development of metallurgy – perhaps one of the oldest crafts, which built on the conquest of fire. Yet, as much as fire contributed to evolutionary change in humans and gave them an advantage (in terms of subjugation) over nonhuman animals and the environment, the use and application of metals presented an additional advantage (in terms of subjugation) over other humans, other groups. This range of applications had substantive cultural and civilisational effects that necessitated radical shifts in the understanding and conceptualising of human existence, during the metal ages and beyond. The use of metals proliferated, not only in warfare and fashion but also in civil engineering, housing, transport and trade.

Iron, however, is brittle until the addition of carbon makes it (just as hard, but also) more resistant to pressure. This was the birth of steel, with early attempts dating back to the time of the first furnaces. Massive production, however, only became possible after an engineer, Henry Bessemer, came up with a method to produce steel in larger quantities.23 Steel meant a fusion of fire, iron and carbon; with the addition of water, it drove the Steam Age, particularly marking the development of the capitalist imperial and colonial regime in Britain, where the heat machine drove ships and trains and weapons and large architectural constructions … and the Enlightenment myth of exponential progress, industrialisation and unhindered modernity.

Steel is most clearly associated with the Industrial Revolution and the Industrial Age. Steam could not have been contained in boilers, leading to pistons that transformed its power into movement, were it not for this strong, durable, yet pliable material that made up the heat engine. There would have been no trains, no massive bridges, no skyscrapers; likewise none of the advances in science and technology that, today, are quite invisible, yet without which many of our daily lives would be inconceivable. The Age of Steam might have been fuelled by wood and coal, but the energy created by burning them drove metal machines, tools, vehicles.

Then again, it was also fuelled by the subjugation of labour – a literal repositioning of labour underground; by extraction, and the Enlightenment decoupling of nature and culture so as to relegate the status of the former (and also the latter) to that of a mere resource, there for the taking. Nigel Clark and Bronislaw Szerszynski argue that the growing importance of subterranean resources led to those doing the work to be viewed as a ‘kind of human subspecies: coal-blackened, benighted, degenerate.’24 What is more, this stratification helped to ‘legitimate – or at least obscure – horrific death rates, crippling health problems and all the indignities [Lewis] Mumford gathers under the term “brutalization”’.25 Steel, then, was a material substrate and epitome of colonial conquest and subordination, demonstrating that the heroic narrative of discovery and exploration also has an oppressive dark side.

The situation continues to this day in the case of the rare metals and earths used in digital technology: cobalt mining in Congo and lithium-related devastation in South America, and similar attempts in Serbia and elsewhere, infamously demonstrate the precarity of the relationship between the social and the cultural and the environment, as well as the excessive planetary power dis-balances of today. The latter have been ongoing at least since the colonisation of the world by western empires after Columbus’s landing in America, leading up to the end of unilateral globalisation and the Anthropocene.26 What is more, what Nigel Clark and Bronislaw Szerszynski call ‘geological othering’ reveals that ‘capitalist accumulation at once – inadvertently – brings to light the evidence of an unstable Earth and – equally inadvertently – exacerbates this instability.’27

Colonialism, a ‘constitutive element of what it meant to be modern and to be European’,28 resulted in the confiscation of territory, subordination of bodies, and the extraction of resources and energy. The necessary condition and effect of this is that, alongside extraction of resources, it also builds, as C. Thi Nguyen maintains, the ‘social, economic, cultural and even attentional environment in ways that get us to follow its [the system’s] game plan’.29 A further consequence, Amílcar Cabral states, is that for its security, imperial domination ‘requires cultural oppression and the attempt at direct or indirect liquidation of the essential elements of the culture of the dominated people’.30

Following these thinkers, Olúfémi O. Táíwò argues that culture, as a collective ability to design and organise our lives, is the engine of history and, as such, conflicts directly with the aims of imperialists to be the ones doing the designing and controlling.31 It is not just about the capture and extraction of land and resources, but also of bodies and minds – that is, the creativity and culture which, in order for any material conquest or subordination to succeed, must effect (to quote Cabral again) ‘permanent, organized repression of the cultural life of the people concerned.'32

Although, to a large extent, colonialism was enabled and driven by the means of western technological advances, among them the steam engine and steel, its history also shows the power of the entanglement between human-made objects and resources. Particularly, it reveals the subjugating power of technology in the dynamics similar to that which Táíwò terms ‘elite capture’: in ‘technology capture’, economic and political power structures emerge out of the imbalances in, restrictions and prevention of, access to technology and resources. This also reveals the conditions that such dynamics require and the effects that they have on planetary sociopolitical, neo-imperialist and neocolonial relations today.

The ‘implements of progress’, however, were also used ‘at home’. For example, the levels of biological and material destruction inflicted by steel-driven World-War-I warfare were such that, even today, large amounts of ammunition, bombs, stretches of barbed wire, and other remnants resurface or are excavated. Recently, with global warming, bodies and objects that have been buried under ice in northern Italy since World War I have begun to surface from underneath the retreating ice and snow.33

The elite capture of technology also necessitated the continuous development of various intra-continental modalities and manifestations of subordination and resistance, notably across the East-West divide. In the latter part of the twentieth century, the divide came to symbolise ideological, political, cultural and technological differences and divisions, but was also reworked in the Non-Aligned Movement, which in the context of anti-colonial and anti-imperial politics and practices demanded more balanced access to, and the development of, technological and economic systems. In light of post-war reconstruction and its offshoot of modernisation, metal was indispensable to civil engineering, the automotive industry and the military-industrial complex.

The massive production of steel and steel objects historically reinforced the workings of the capitalist regime, in terms of the interrelation of over-production and over-consumption, which became apparent in the production of both weapons and quotidian objects (knives, hairpins, boxes and flasks, cars, etc.). The former entails the need to extract-to-produce (resources and labour), disregarding the consequences, and, on the consumptive end, not only consumer-consumption but also the need for the energy-to-produce. The history of steel production and its uses presents a precursor to the drive to produce-to-consume whose extreme formation became radically apparent with the invention, popularisation and mass production of plastic. Plastic, in its ready availability, multi-applicability and non-degradability, further concealed the destructive power of excessive energy demand as well as the planetary injustices, disbalances, disregard and disrespect – perhaps most painfully visible in the mountains of discarded clothes exported to Ghana or the vortex of plastic in the Pacific Ocean, only the most mediated examples of displaced industrial-scale waste and pollution.

Nicolas Bourriaud notes we are in a situation where ‘things and phenomena used to surround us. Today it seems they threaten us in ghostly form, as unruly scraps that refuse to go away or persist even after vanishing into the air.’34 The obsession with the production of stuff and the dispensation of waste and energy seems like a sinister offshoot of that other contemporary obsession with feeding the insatiable archive – one that knows no boundaries, and that colonises capacities and resources in order to store and retrieve. Bourriaud continues: ‘Ours is also an epoch of squandered energy: nuclear waste that won’t go away, hulking stockpiles of unused goods, and domino effects triggered by industrial emissions polluting the atmosphere and oceans.’35

As much as humans overproduce, then, they also overconsume – not just objects but energy too, which puts the human:world relationship in a particularly precarious frame. This precarity not only exposes the disbalances of power and the subjugation of and by other humans, but also the fragility of the Earth as a system. Further, it unmasks the unimaginable forces of nature, which can crush concrete and deform steel, as we’ve most recently seen with the massive fires and floods of the summer of 2023.

**

Particles, in terms of visibility and timescales, are the constituent elements of the universe. Hidden ‘behind’, ‘beneath’ or ‘within’ stuff, particles are the first and least complex ‘thing’ to be formed when the universe big-banged into existence. As such, they comprise everything in existence and mark the birth of cosmic history and time stretching back fourteen million years.

The cosmic evolution, however, was neither deterministic nor progressive, states astrophysicist Eric J. Chaisson. Rather, it was the interplay of ‘chance and necessity [that] meander throughout all aspects of the cosmic-evolutionary scenario, whose temporal “arrow” hereby represents a convenient symbolic guide to natural history’s varied changes.’36 And change seems to be happening in the direction of the rise of ‘order, form, structure, complexity, organisation, information, inhomogeneity, clumpiness’, meaning the development and evolution of localised material assemblages – ‘systems’ – throughout the history of the universe.37

It took thousands of years to develop instruments and knowledge to enable humans to detect and understand the invisible composition of the universe or cosmic expansion. According to Chaisson, along with the ‘gravitational force in physics, natural selection in biology, and technological innovation in culture’, cosmic expansion is one of the preconditions for the evolution of order and the emergence of increasingly complex systems. The organised dynamics ‘established the temperature gradients, began the free energy flowing, and fostered environmental changes literally everywhere.’38 Thus, we can see its systemising effects on humans’ perception of and relationship to ‘nature’, as well as on the formation of society and culture.

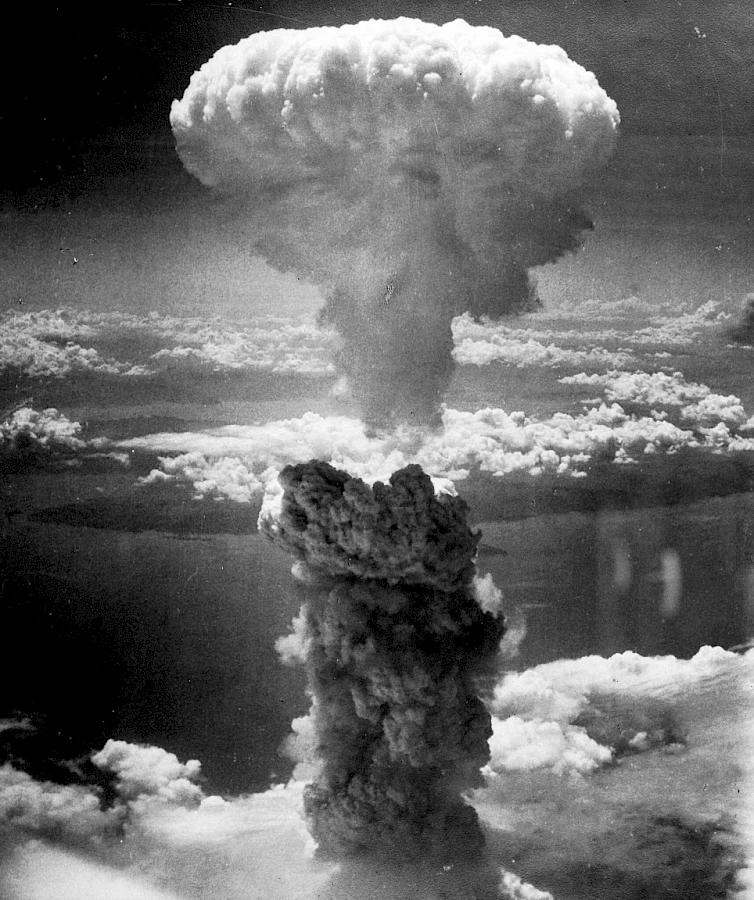

Yet, particles as carriers of energy have likewise been subject to attempts at subordination in human:tech activities. Light, the condition of life itself (and symbolically related to the acquisition of knowledge) is used in solar electricity production. Radiation, the least visible and most fearsome manifestation of particles in action, bears the promise of endless energy supply; but also of destruction, as was seen when the US dropped A-bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, not to mention the destructive post–World-War-II nuclear testing in the Pacific and elsewhere, or the nuclear plant disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima, or most recently, the fear of nuclear power plants being weaponised in the war in Ukraine.

Another indicator of the seminality and everyday application of particle physics and related sciences is that time – that is, the age of objects and phenomena – in geology and archaeology, is now measured in relation to the discovery of radiocarbon dating, setting the beginning of the present on 1 January 1950. Subsequently, everything that happened before that date became Before Present (BP). Carbon-dating methods not only enable us to establish the timeframe of events in the very distant past, such as the various uses and applications of fire or the history of ironworking, but also facilitate the understanding of the formation and expansion of the universe, as well as other astro- and terrestrial geological events and processes that have shaped and, in the Anthropocene, with human assistance, continue to shape the conditions of, and changes to, the systems we call Earth.

The Atomic Era, in which the binary world of the post–World-War-II period was steeped, was characterised by hopes and fears: by ideas of even more progress, of flying cars and interstellar journeys, but also by the fear of DNA mutations and mutually assured destruction as a consequence of the Cold War arms race. As a referential frame of progress, this left an indelible mark on the latter part of the twentieth century until it receded in light of the collapse of state socialism.

The post-war dream was gradually replaced by the mass realisation of human-induced changes and damage to the planet and the life on it, and the need to come up with alternative sources of energy.39 In this transformation, it became apparent that, just as carbon was implicated in fire, so it was in the production of steel, and so inadvertently in histories of subjugation and power disbalances, colonialism and imperialism. Carbon was, and is, therefore critical in understanding the deep-time perspective and that of cosmic evolution. As a pharmakon proper, carbon is the enabler of carbon-based lifeforms but it is also a life-threatening element, and as such a marker of contemporary life. According to McKenzie Wark, the carbon being ‘liberated’ with the use of fossil fuels is inherently an element that marks the modern era:

The history of the modern world from the French Revolution onwards is often thought of as a series of liberations – from tyranny, from mystification, and so on. Or, more positively, the liberation of the common people, of the slaves, of women, and so on. There’s even a movement now for animal liberation. But what if the thing that really got free in modern times was nothing human or even animal, but was an element: carbon? Capitalism runs on fossil fuels – on carbon. It “liberates” it from oil and coal deposits, runs the commodity economy on it, and dumps the waste carbon in the atmosphere and the oceans.40

**

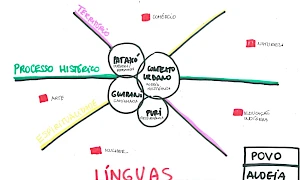

This short techno-cultural overview of fire, steel and particles is western-biased. While it hopes to provoke responses from different parts of the world, different epistemologies and technologies, imaginations and knowledges, and cosmotechnics, it is an embodiment of the fact that western civilisation, with its dominant technological systems, sciences and definition of reason have exerted massive influence on the world, not least through colonialism and imperial expansion. This contributes to obscuring the fact that not all technologies were and are conceived, developed and used in the same way, and expose the need to bring in view other, indigenous technologies, different epistemologies. Yuk Hui observes a tension in this regard:

Thesis: Technology is an anthropological universal, understood as an exteriorization of memory and the liberation of organs, as some anthropologists and philosophers of technology have formulated it; Antithesis: Technology is not anthropologically universal; it is enabled and constrained by particular cosmologies, which go beyond mere functionality or utility. Therefore, there is no one single technology, but rather multiple cosmotechnics.41

Incorporating the idea of cosmotechnics, this text acknowledges that, indeed, there are great inequalities and power disbalances: not just among humans, with numerous populations living without, or in the shadow of, historical conditions that have been played out in such a way as to recalcitrate and naturalise these disbalances, but also in relationships to the planet and to climate change, as well to the systems of different epistemologies and imaginations.42

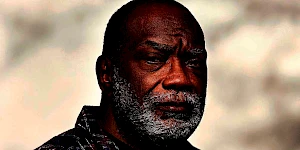

Achille Mbembe importantly establishes the connection between the material conditions of human existence and subjugation, and the link that interests us here:

The question of the world – what it is, what the relationship is between its various parts, what the extent of its resources is and to whom they belong, how to live in it, what moves and threatens it, where it is going, what its borders and limits, and its possible end, are – has been within us since a human being of bone, flesh, and spirit made its first appearance under the sign of the Black Man, as human-merchandise, human-metal, and human-money. Fundamentally, it was always our question. And it will stay that way as long as speaking the world is the same as declaring humanity, and vice versa.43

This writing, therefore, is an attempt to stir the imagination towards the opening up of discursive and epistemological boundaries, to bridge imagination and knowledge, and to construct in-between spaces for the interaction of different histories, presents and possible futures, which exist ‘behind’, ‘beyond’ or ‘on the other side of’ dominant ways of knowing and interpreting.

It is an attempt to make you/one/us think about what makes the world: what makes it liveable, what makes it worthwhile to try not just to understand, but to endow with meaning.

It is an appeal to probe the limits of, and potentials for, future world-making in different historical and civilisational contexts, through thinking of different pasts, presents and possible futures – indeed, different cosmotechnics and cosmopolitics – with a view to acknowledging the complexities and disbalances of the present, and to subsequently creating an opportunity to move from subsistence to coexistence.

**

Now, so as to not just ‘wrap up’ but rather to hint at the open, the unplanned, the unexpected, by means of a slight detour – this book hopes not only to contribute to the understanding of the past and the present, but also to address the future, taking inspiration from Ursula K. Le Guin’s ‘Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’. Le Guin, following Elizabeth Fisher’s ‘Carrier Bag Theory of Evolution’,44 proposed to decentre the interpretation that the formation of culture and civilisation rested on the spear-wielding he-hunters who shared heroic hunting stories by the fire. Instead, she proposes a focus on the carrier bag as the technology that was used to store not only nuts for tomorrow but also valuable items around which memories and stories were woven, narratives of evolution formed, and around which, humanity became.

As a technology of memory and human civilisation the carrier bag (that could also be a book) may precede the hunting and the usual heroics. It allows us to centre that which makes us human: stories, memories, dreams, creation, experiment, knowledge, experience. Similarly, this book attempts to borrow this logic: it does not aim to narrate the hegemonic stories of the heroic conquest of nature or the other, but instead to serve as a carrier bag of knowledge and imagination, of stories and theories, for the future.

Inasmuch as it takes fire to warm the bones and provide for a home, inasmuch as it takes metal to make a nail or a spaceship, and inasmuch as it takes the understanding of the elements and particles to understand ‘nature’ and to create (and destroy), it primarily and primordially takes a story to know and to relate, to make sense of ourselves and others and the world.

This book-in-the-making thus hopes to provide a space in which to bring together scientists and artists of different callings and backgrounds: physicists and writers, biologists, astrophysicists and anthropologists, political scientists, mathematicians and poets and painters, digital artists and photographers (for every and there is an or, too).

Within the limits of the print format – yet while experimenting with textual and visual forms – this book hopes to be a space in which to uncover and retell the underlying phenomena of extraction and destruction; of building and rebuilding; of creating and changing; of conquest and subordination; of the relationships that exist between humans, elements, nonhuman animals and the Earth, its minerals and soils – in terms of, and refracted through, fire, steel and particles.

Related activities

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum I

The Climate Forum is a space of dialogue and exchange with respect to the concrete operational practices being implemented within the art field in response to climate change and ecological degradation. This is the first in a series of meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L'Internationale's Museum of the Commons programme.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

The Soils Project

‘The Soils Project’ is part of an eponymous, long-term research initiative involving TarraWarra Museum of Art (Wurundjeri Country, Australia), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands) and Struggles for Sovereignty, a collective based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. It works through specific and situated practices that consider soil, as both metaphor and matter.

Seeking and facilitating opportunities to listen to diverse voices and perspectives around notions of caring for land, soil and sovereign territories, the project has been in development since 2018. An international collaboration between three organisations, and several artists, curators, writers and activists, it has manifested in various iterations over several years. The group exhibition ‘Soils’ at the Van Abbemuseum is part of Museum of the Commons. -

–VCRC

Kyiv Biennial 2023

L’Internationale Confederation is a proud partner of this year’s edition of Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

Where are the Oases?

PEI OBERT seminar

with Kader Attia, Elvira Dyangani Ose, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Emily Jacir, Achille Mbembe, Sarah Nuttall and Françoise VergèsAn oasis is the potential for life in an adverse environment.

-

MACBA

Anti-imperialism in the 20th century and anti-imperialism today: similarities and differences

PEI OBERT seminar

Lecture by Ramón GrosfoguelIn 1956, countries that were fighting colonialism by freeing themselves from both capitalism and communism dreamed of a third path, one that did not align with or bend to the politics dictated by Washington or Moscow. They held their first conference in Bandung, Indonesia.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production

The Studies Center of Museo Reina Sofía will publish an open call for four residencies of artistic practice for projects that address the emergencies and challenges derived from the climate crisis such as food sovereignty, architecture and sustainability, communal practices, diasporas and exiles or ecological and political sustainability, among others.

-

–Van Abbemuseum

Maria Lugones Decolonial Summer School

Recalling Earth: Decoloniality and Demodernity

Course Directors: Prof. Walter Mignolo & Dr. Rolando VázquezRecalling Earth and learning worlds and worlds-making will be the topic of chapter 14th of the María Lugones Summer School that will take place at the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven.

-

–tranzit.ro

Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

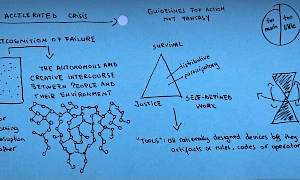

The experimental course ‘Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life’ (November 2023–May 2024) celebrates as its starting point the anniversary of 50 years since the publication of Tools for Conviviality, considering that Ivan Illich’s call is as relevant as ever.

-

–MSN Warsaw

Archive of the Conceptual Art of Odesa in the 1980s

The research project turns to the beginning of 1980s, when conceptual art circle emerged in Odesa, Ukraine. Artists worked independently and in collaborations creating the first examples of performances, paradoxical objects and drawings.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school is organised by Moderna galerija in Ljubljana in partnership with ZRC SAZU (the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts) as part of the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons.

-

–Moderna galerijaZRC SAZU

Open Call – Summer School: Our Many Easts

Our Many Easts summer school takes place in Ljubljana 24–30 August and the application deadline is 15 March. Courses will be held in English and cover topics such as the legacy of the Eastern European avant-gardes, archives as tools of emancipation, the new “non-aligned” networks, art in times of conflict and war, ecology and the environment.

-

–MACBA

Song for Many Movements: Scenes of Collective Creation

An ephemeral experiment in which the ground floor of MACBA becomes a stage for encounters, conversations and shared listening.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ in Venice at Sale Docks is a four-day programme curated by Institute of Radical Imagination (IRI) and Sale Docks.

-

–Institute of Radical Imagination

Gathering into the Maelstrom (exhibition)

‘Gathering into the Maelstrom’ is curated by Institute of Radical Imagination and Sale Docks within the framework of Museum of the Commons.

-

–M HKA

The Lives of Animals

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at M HKA that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ is a series of sound installations by Özcan Ertek, Fulya Uçanok, Ömer Sarıgedik, Zeynep Ayşe Hatipoğlu, and Passepartout Duo, presented at Salt in Istanbul.

-

–SALT

Sound of Green

‘Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them’ at Salt in Istanbul begins on 5 June, World Environment Day, with Özcan Ertek’s installation ‘Sound of Green’.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Palestine Is Everywhere

‘Palestine Is Everywhere’ is an encounter and screening at Museo Reina Sofía organised together with Cinema as Assembly as part of Museum of the Commons. The conference starts at 18:30 pm (CET) and will also be streamed on the online platform linked below.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Open Call: Research Residencies

The Centro de Estudios of Museo Reina Sofía releases its open call for research residencies as part of the climate thread within the Museum of the Commons programme.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum II

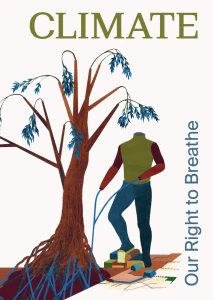

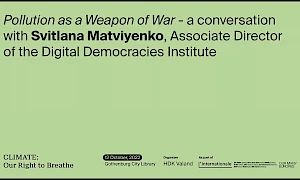

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum III

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

MACBA

The Open Kitchen. Food networks in an emergency situation

with Marina Monsonís, the Cabanyal cooking, Resistencia Migrante Disidente and Assemblea Catalana per la Transició Ecosocial

The MACBA Kitchen is a working group situated against the backdrop of ecosocial crisis. Participants in the group aim to highlight the importance of intuitively imagining an ecofeminist kitchen, and take a particular interest in the wisdom of individuals, projects and experiences that work with dislocated knowledge in relation to food sovereignty. -

–

Kyiv Biennial 2025

L’Internationale Confederation is proud to co-organise this years’ edition of the Kyiv Biennial.

-

–MACBA

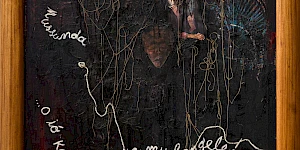

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica

Curated by MACBA director Elvira Dyangani Ose, along with Antawan Byrd, Adom Getachew and Matthew S. Witkovsky, Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica is the first major international exhibition to examine the cultural manifestations of Pan-Africanism from the 1920s to the present.

-

–M HKA

The Geopolitics of Infrastructure

The exhibition The Geopolitics of Infrastructure presents the work of a generation of artists bringing contemporary perspectives on the particular topicality of infrastructure in a transnational, geopolitical context.

-

–MACBAMuseo Reina Sofia

School of Common Knowledge 2025

The second iteration of the School of Common Knowledge will bring together international participants, faculty from the confederation and situated organizations in Barcelona and Madrid.

-

–SALT

The Lives of Animals, Salt Beyoğlu

‘The Lives of Animals’ is a group exhibition at Salt that looks at the subject of animals from the perspective of the visual arts.

-

–SALT

Plant(ing) Entanglements

The series of sound installations Warm Earth Sounds for Plants and the People Who Love Them ends with Fulya Uçanok’s sound installation Plant(ing) Entanglements.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Sustainable Art Production. Research Residencies

The projects selected in the first call of the Sustainable Art Practice research residencies are A hores d'ara. Experiences and memory of the defense of the Huerta valenciana through its archive by the group of researchers Anaïs Florin, Natalia Castellano and Alba Herrero; and Fundamental Errors by the filmmaker and architect Mauricio Freyre.

-

–

Collective Study in Times of Emergency, Amsterdam

Within the context of ‘Every Act of Struggle’, the research project and exhibition at de appel in Amsterdam, L’Internationale Online has been invited to propose a programme of collective study.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Poetry readings: Culture for Peace – Art and Poetry in Solidarity with Palestine

Casa de Campo, Madrid

-

–IMMANCAD

Summer School: Landscape (post) Conflict

The Irish Museum of Modern Art and the National College of Art and Design, as part of L’internationale Museum of the Commons, is hosting a Summer School in Dublin between 7-11 July 2025. This week-long programme of lectures, discussions, workshops and excursions will focus on the theme of Landscape (post) Conflict and will feature a number of national and international artists, theorists and educators including Jill Jarvis, Amanda Dunsmore, Yazan Kahlili, Zdenka Badovinac, Marielle MacLeman, Léann Herlihy, Slinko, Clodagh Emoe, Odessa Warren and Clare Bell.

-

HDK-Valand

Climate Forum IV

The Climate Forum is a series of online meetings hosted by HDK-Valand within L’Internationale’s Museum of the Commons programme. The series builds upon earlier research resulting in the (2022) book Climate: Our Right to Breathe and reaches toward emerging change practices.

-

–Museo Reina Sofia

Study Group: Aesthetics of Peace and Desertion Tactics

In a present marked by rearmament, war, genocide, and the collapse of the social contract, this study group aims to equip itself with tools to, on one hand, map genealogies and aesthetics of peace – within and beyond the Spanish context – and, on the other, analyze strategies of pacification that have served to neutralize the critical power of peace struggles.

-

–MSU Zagreb

October School: Moving Beyond Collapse: Reimagining Institutions

The October School at ISSA will offer space and time for a joint exploration and re-imagination of institutions combining both theoretical and practical work through actually building a school on Vis. It will take place on the island of Vis, off of the Croatian coast, organized under the L’Internationale project Museum of the Commons by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and the Island School of Social Autonomy (ISSA). It will offer a rich program consisting of readings, lectures, collective work and workshops, with Adania Shibli, Kristin Ross, Robert Perišić, Saša Savanović, Srećko Horvat, Marko Pogačar, Zdenka Badovinac, Bojana Piškur, Theo Prodromidis, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Progressive International, Naan-Aligned cooking, and others.

-

–MSN Warsaw

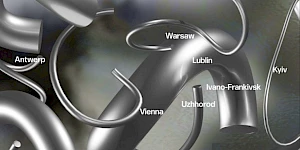

Near East, Far West. Kyiv Biennial 2025

The main exhibition of the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, titled Near East, Far West, is organized by a consortium of curators from L’Internationale. It features seven new artists’ commissions, alongside works from the collections of member institutions of L’Internationale and a number of other loans.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: The Brighter Nations in Solidarity: Even in the Midst of a Genocide, a New World Is Being Born

PEI Obert presents a lecture by Vijay Prashad. The Colonial West is in decay, losing its economic grip on the world and its control over our minds. The birth of a new world is neither clear nor easy. This talk envisions that horizon, forged through the solidarity of past and present anticolonial struggles, and heralds its inevitable arrival.

-

–M HKA

Homelands and Hinterlands. Kyiv Biennial 2025

Following the trans-national format of the 2023 edition, the Kyiv Biennial 2025 will again take place in multiple locations across Europe. Museum of Contemporary Art Antwerp (M HKA) presents a stand-alone exhibition that acts also as an extension of the main biennial exhibition held at the newly-opened Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN).

In reckoning with the injustices and atrocities committed by the imperialisms of today, Kyiv Biennial 2025 reflects with historical consciousness on failed solidarities and internationalisms. It does this across an axis that the curators describe as Middle-East-Europe, a term encompassing Central Eastern Europe, the former-Soviet East and the Middle East.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Nour Shantout

In this artist talk, Nour Shantout will present Searching for the New Dress, an ongoing artistic research project that looks at Palestinian embroidery in Shatila, a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. Welcome!

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Bodies of Evidence. A lecture by Ido Nahari and Adam Broomberg

In the second day of Open PEI, writer and researcher Ido Nahari and artist, activist and educator Adam Broomberg bring us Bodies of Evidence, a lecture that analyses the circulation and functioning of violent images of past and present genocides. The debate revolves around the new fundamentalist grammar created for this documentation.

-

–

Everything for Everybody. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Everything for Everybody’ takes place in the Ukraine, at the Dnipro Center for Contemporary Culture.

-

–

In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘In a Grandiose Sundance, in a Cosmic Clatter of Torture’ takes place at the Dovzhenko Centre in Kyiv.

-

MACBA

School of Common Knowledge: Fred Moten

Fred Moten gives the lecture Some Prœposicions (On, To, For, Against, Towards, Around, Above, Below, Before, Beyond): the Work of Art. As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA presents this lecture on artworks and art institutions in relation to the challenge of blackness in the present day.

-

–MACBA

Visions of Panafrica. Film programme

Visions of Panafrica is a film series that builds on the themes explored in the exhibition Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, bringing them to life through the medium of film. A cinema without a geographical centre that reaffirms the cultural and political relevance of Pan-Africanism.

-

MACBA

Farah Saleh. Balfour Reparations (2025–2045)

As part of the Project a Black Planet exhibition, MACBA is co-organising Balfour Reparations (2025–2045), a piece by Palestinian choreographer Farah Saleh included in Hacer Historia(s) VI (Making History(ies) VI), in collaboration with La Poderosa. This performance draws on archives, memories and future imaginaries in order to rethink the British colonial legacy in Palestine, raising questions about reparation, justice and historical responsibility.

-

MACBA

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica OPENING EVENT

A conversation between Antawan I. Byrd, Adom Getachew, Matthew S. Witkovsky and Elvira Dyangani Ose. To mark the opening of Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, the curatorial team will delve into the exhibition’s main themes with the aim of exploring some of its most relevant aspects and sharing their research processes with the public.

-

MACBA

Palestine Cinema Days 2025: Al-makhdu’un (1972)

Since 2023, MACBA has been part of an international initiative in solidarity with the Palestine Cinema Days film festival, which cannot be held in Ramallah due to the ongoing genocide in Palestinian territory. During the first days of November, organizations from around the world have agreed to coordinate free screenings of a selection of films from the festival. MACBA will be screening the film Al-makhdu’un (The Dupes) from 1972.

-

Museo Reina Sofia

Cinema Commons #1: On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes

On the Art of Occupying Spaces and Curating Film Programmes is a Museo Reina Sofía film programme overseen by Miriam Martín and Ana Useros, and the first within the project The Cinema and Sound Commons. The activity includes a lecture and two films screened twice in two different sessions: John Ford’s Fort Apache (1948) and John Gianvito’s The Mad Songs of Fernanda Hussein (2001).

-

–

Vertical Horizon. Kyiv Biennial 2025

As one of five exhibitions comprising the 6th Kyiv Biennial 2025, ‘Vertical Horizon’ takes place at the Lentos Kunstmuseum in Linz, at the initiative of tranzit.at.

-

HDK-Valand

MA Forum in collaboration with LIO: Adam Broomberg

In this MA Forum we welcome artist Adam Broomberg. In his lecture he will focus on two photographic projects made in Israel/Palestine twenty years apart. Both projects use the medium of photography to communicate the weaponization of nature.

-

MACBA

PEI Obert: Until Liberation: A Collective Reading and Listening Session by Learning Palestine

PEI Obert presents a collective session with Learning Palestine. At this historical juncture – amid the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the censorship and repression of all things Palestinian – Learning Palestine invites us to gather not only in refusal but also in affirmation.

Related contributions and publications

-

Decolonial aesthesis: weaving each other

Charles Esche, Rolando Vázquez, Teresa Cos RebolloLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum I – Readings

Nkule MabasoEN esLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

…and the Earth along. Tales about the making, remaking and unmaking of the world.

Martin PogačarLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Art for Radical Ecologies Manifesto

Institute of Radical ImaginationLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Pollution as a Weapon of War

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimate -

The Kitchen, an Introduction to Subversive Film with Nick Aikens, Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi

Nick Aikens, Subversive FilmSonic and Cinema CommonslumbungPast in the PresentVan Abbemuseum -

The Repressive Tendency within the European Public Sphere

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Ecologising Museums

Land Relations -

Climate: Our Right to Breathe

Land RelationsClimate -

A Letter Inside a Letter: How Labor Appears and Disappears

Marwa ArsaniosLand RelationsClimate -

Troubles with the East(s)

Bojana PiškurInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Right now, today, we must say that Palestine is the centre of the world

Françoise VergèsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Body Counts, Balancing Acts and the Performativity of Statements

Mick WilsonInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation I

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Until Liberation II

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Seeds Shall Set Us Free II

Munem WasifLand RelationsClimate -

Pollution as a Weapon of War – a conversation with Svitlana Matviyenko

Svitlana MatviyenkoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Françoise Vergès – Breathing: A Revolutionary Act

Françoise VergèsClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Ana Teixeira Pinto – Fire and Fuel: Energy and Chronopolitical Allegory

Ana Teixeira PintoClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

Watery Histories – a conversation between artists Katarina Pirak Sikku and Léuli Eshrāghi

Léuli Eshrāghi, Katarina Pirak SikkuClimateClimate book launchHDK-Valand -

The Veil of Peace

Ovidiu ŢichindeleanuPast in the Presenttranzit.ro -

Editorial: Towards Collective Study in Times of Emergency

L’Internationale Online Editorial BoardEN es sl tr arInternationalismsStatements and editorialsPast in the Present -

Opening Performance: Song for Many Movements, live on Radio Alhara

Jokkoo with/con Miramizu, Rasheed Jalloul & Sabine SalaméEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

Siempre hemos estado aquí. Les poetas palestines contestan

Rana IssaEN es tr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Discomfort at Dinner: The role of food work in challenging empire

Mary FawzyLand RelationsSituated Organizations -

Indra's Web

Vandana SinghLand RelationsPast in the PresentClimate -

Diary of a Crossing

Baqiya and Yu’adInternationalismsPast in the Present -

The Silence Has Been Unfolding For Too Long

The Free Palestine Initiative CroatiaInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated OrganizationsInstitute of Radical ImaginationMSU Zagreb -

En dag kommer friheten att finnas

Françoise Vergès, Maddalena FragnitoEN svInternationalismsLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Art and Materialisms: At the intersection of New Materialisms and Operaismo

Emanuele BragaLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Dispatch: Harvesting Non-Western Epistemologies (ongoing)

Adelina LuftLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: From the Eleventh Session of Non-Western Technologies for the Good Life

Ana KunLand RelationsSchoolstranzit.ro -

War, Peace and Image Politics: Part 1, Who Has a Right to These Images?

Jelena VesićInternationalismsPast in the PresentZRC SAZU -

Dispatch: Practicing Conviviality

Ana BarbuClimateSchoolsLand Relationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: Notes on Separation and Conviviality

Raluca PopaLand RelationsSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimatetranzit.ro -

Dispatch: The Arrow of Time

Catherine MorlandClimatetranzit.ro -

To Build an Ecological Art Institution: The Experimental Station for Research on Art and Life

Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Raluca VoineaLand RelationsClimateSituated Organizationstranzit.ro -

Dispatch: A Shared Dialogue

Irina Botea Bucan, Jon DeanLand RelationsSchoolsClimatetranzit.ro -

Art, Radical Ecologies and Class Composition: On the possible alliance between historical and new materialisms

Marco BaravalleLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Live set: Una carta de amor a la intifada global

PrecolumbianEN esInternationalismsSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the PresentMACBA -

‘Territorios en resistencia’, Artistic Perspectives from Latin America

Rosa Jijón & Francesco Martone (A4C), Sofía Acosta Varea, Boloh Miranda Izquierdo, Anamaría GarzónLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Unhinging the Dual Machine: The Politics of Radical Kinship for a Different Art Ecology

Federica TimetoLand RelationsClimateInstitute of Radical Imagination -

Cultivating Abundance

Åsa SonjasdotterLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Reading list - Summer School: Our Many Easts

Summer School - Our Many EastsSchoolsPast in the PresentModerna galerija -

The Genocide War on Gaza: Palestinian Culture and the Existential Struggle

Rana AnaniInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Climate Forum II – Readings

Nick Aikens, Nkule MabasoLand RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Klei eten is geen eetstoornis

Zayaan KhanEN nl frLand RelationsClimatePast in the Present -

Dispatch: ‘I don't believe in revolution, but sometimes I get in the spirit.’

Megan HoetgerSchoolsPast in the Present -

Dispatch: Notes on (de)growth from the fragments of Yugoslavia's former alliances

Ava ZevopSchoolsPast in the Present -

Glöm ”aldrig mer”, det är alltid redan krig

Martin PogačarEN svLand RelationsPast in the Present -

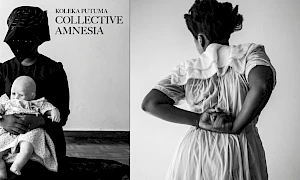

Graduation

Koleka PutumaLand RelationsClimate -

Depression

Gargi BhattacharyyaLand RelationsClimate -

Climate Forum III – Readings

Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand RelationsClimate -

Soils

Land RelationsClimateVan Abbemuseum -

Dispatch: There is grief, but there is also life

Cathryn KlastoLand RelationsClimate -

Beyond Distorted Realities: Palestine, Magical Realism and Climate Fiction

Sanabel Abdel RahmanEN trInternationalismsPast in the PresentClimate -

Dispatch: Care Work is Grief Work

Abril Cisneros RamírezLand RelationsClimate -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency. A Roundtable

Nick Aikens, Sara Buraya Boned, Charles Esche, Martin Pogačar, Ovidiu Ţichindeleanu, Ezgi YurteriInternationalismsPast in the PresentSituated Organizations -

Present Present Present. On grounding the Mediateca and Sonotera spaces in Malafo, Guinea-Bissau

Filipa CésarSonic and Cinema CommonsPast in the Present -

Collective Study in Times of Emergency

InternationalismsPast in the Present -

ميلاد الحلم واستمراره

Sanaa SalamehEN hr arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

عن المكتبة والمقتلة: شهادة روائي على تدمير المكتبات في قطاع غزة

Yousri al-GhoulEN arInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio I. Internacionalismo radical y panafricanismo en el marco de la guerra civil española

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Re-installing (Academic) Institutions: The Kabakovs’ Indirectness and Adjacency

Christa-Maria Lerm HayesInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Palma daktylowa przeciw redeportacji przypowieści, czyli europejski pomnik Palestyny

Robert Yerachmiel SnidermanEN plInternationalismsPast in the PresentMSN Warsaw -

Masovni studentski protesti u Srbiji: Mogućnost drugačijih društvenih odnosa

Marijana Cvetković, Vida KneževićEN rsInternationalismsPast in the Present -

No Doubt It Is a Culture War

Oleksiy Radinsky, Joanna ZielińskaInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Lives of Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimateM HKA -

Sonic Room: Translating Animals

Joanna ZielińskaLand RelationsClimate -

Encounters with Ecologies of the Savannah – Aadaajii laɗɗe

Katia GolovkoLand RelationsClimate -

Trans Species Solidarity in Dark Times

Fahim AmirEN trLand RelationsClimate -

Dispatch: As Matter Speaks

Yeongseo JeeInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading List: Summer School, Landscape (post) Conflict

Summer School - Landscape (post) ConflictSchoolsLand RelationsPast in the PresentIMMANCAD -

Solidarity is the Tenderness of the Species – Cohabitation its Lived Exploration

Fahim AmirEN trLand Relations -

Dispatch: Reenacting the loop. Notes on conflict and historiography

Giulia TerralavoroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Haunting, cataloging and the phenomena of disintegration

Coco GoranSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landescape – bending words or what a new terminology on post-conflict could be

Amanda CarneiroSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Landscape (Post) Conflict – Mediating the In-Between

Janine DavidsonSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Excerpts from the six days and sixty one pages of the black sketchbook

Sabine El ChamaaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Dispatch: Withstanding. Notes on the material resonance of the archive and its practice

Giulio GonellaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Climate Forum IV – Readings

Merve BedirLand RelationsHDK-Valand -

Land Relations: Editorial

L'Internationale Online Editorial BoardLand Relations -

Dispatch: Between Pages and Borders – (post) Reflection on Summer School ‘Landscape (post) Conflict’

Daria RiabovaSchoolsLand RelationsIMMANCAD -

Between Care and Violence: The Dogs of Istanbul

Mine YıldırımLand Relations -

Until Liberation III

Learning Palestine GroupInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Archivos negros: Episodio II. Jazz sin un cuerpo político negro

Tania Safura AdamEN esInternationalismsPast in the Present -

Reading list: October School. Reimagining Institutions

October SchoolSchoolsSituated OrganizationsClimateMSU Zagreb -

The Debt of Settler Colonialism and Climate Catastrophe

Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Olivier Marbœuf, Samia Henni, Marie-Hélène Villierme and Mililani GanivetLand Relations -

Cultural Workers of L’Internationale mark International Day of Solidarity with the Palestinian People

Cultural Workers of L’InternationaleEN es pl roInternationalismsSituated OrganizationsPast in the PresentStatements and editorials -

We, the Heartbroken, Part II: A Conversation Between G and Yolande Zola Zoli van der Heide

G, Yolande Zola Zoli van der HeideLand Relations -

Poetics and Operations

Otobong Nkanga, Maya TountaLand Relations -

Breaths of Knowledges

Robel TemesgenClimateLand Relations -

Algumas coisas que aprendemos: trabalhando com cultura indígena em instituições culturais

Sandra Ara Benites, Rodrigo Duarte, Pablo LafuenteEN ptLand Relations -

How to Keep On Without Knowing What We Already Know, Or, What Comes After Magic Words and Politics of Salvation

Mônica HoffClimate -

Conversation avec Keywa Henri

Keywa Henri, Anaïs RoeschEN frLand Relations -

Mgo Ngaran, Puwason (Manobo language) Sa Kada Ngalan, Lasang (Sugbuanon language) Sa Bawat Ngalan, Kagubatan (Filipino) For Every Name, a Forest (English)

Kulagu Tu BuvonganLand Relations -

Making Ground

Kasangati Godelive Kabena, Nkule MabasoLand Relations -

The Climate Reader: Propositions, poetics, operations

Land RelationsClimateHDK-Valand -

Can the artworld strike for climate? Three possible answers

Jakub DepczyńskiLand Relations -

The Object of Value

SlinkoInternationalismsLand Relations